Margaret Stewart, art director, on Jan. 22, 1974.Dennis Robinson/The Globe and Mail

In a career marked by fierce determination to overcome sexism, Margaret Jean Stewart became the first female art director of this newspaper’s weekly feature supplement, The Globe Magazine, in 1963. Then, in 1971, she became The Globe and Mail’s first art director, a role she helped define, since newspapers were laid out by compositors then, not designers. Art directors were regarded as decorators rather than informed visual communicators at the time, recalls publisher John Macfarlane, who also worked at The Globe then. This perception made the job all the more challenging for Ms. Stewart.

A glass ceiling usually kept women from attaining such roles, says René Milot, an illustrator Ms. Stewart frequently commissioned, which makes her accomplishments all the more noteworthy. Female art directors (and editors) were mainly relegated to women’s magazines – and those rare ones who weren’t have been overlooked in design history, according to Brian Donnelly, a historian of Canadian graphic design. Mr. Donnelly had not heard of Ms. Stewart.

No wonder Ms. Stewart remarked, “My work history is interesting as I was one of the first women art directors in Toronto – but maybe only interesting to me,” when, in 2011, she began describing her four-decade influence on Canadian design to this writer. Marg Stewart died peacefully of natural causes on May 30 in Halifax. She was 90.

Ms. Stewart – Marg to her friends – was sometimes acerbic in her letters, criticizing current design trends that she still acutely followed. With her no-nonsense approach, Mr. Milot remembers, she was considered “scary” by some, but he and other illustrators with whom she worked regularly found her refreshingly clear in her expectations: “Women that I worked with in those years told me that in order to succeed and get respect, they had to play the men’s game and become a bit bossy to assert their position.”

In 2015, Ms. Stewart herself advised, “NEVER back down from a confrontation and never show fear. It stood me in good stead in the work force.”

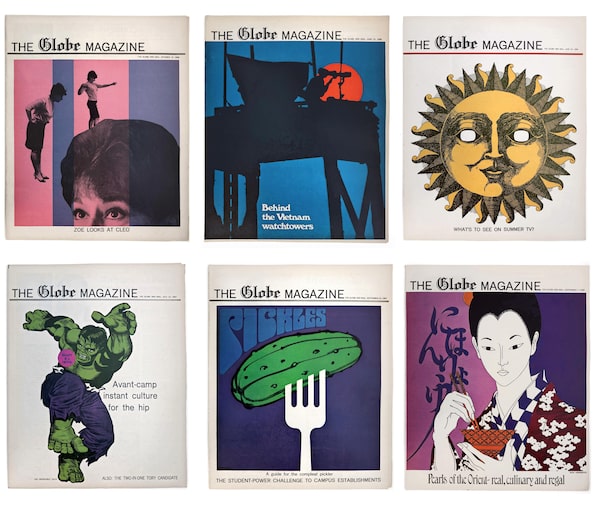

Her striking cover designs for The Globe Magazine captured the dynamism of the 1960s. It was the heyday of Toronto’s celebrity media theorist Marshall McLuhan, whose axiom “the medium is the message” she understood thoroughly, exploiting newsprint’s large format and bold colour to imbue the paper with vivacious hipness.

A selection of covers designed by Margaret Stewart in late sixties for The Globe Magazine, the Globe and Mail's weekend feature magazine.The Globe and Mail

Even so, Ms. Stewart said, “People looked down on The Globe Magazine because of the newsprint. But it was a great product. Very few ads, good content, good art and produced weekly.” Through it, she broadened Canada’s aesthetic horizons. “I’ve decided that I possibly was (and still am) somewhat of a snob about illustration,” she admitted. “Being a super draftsman was just not enough – I wanted individuality as well [from illustrators].” David Chestnutt and Huntley Brown remember that she gave them freedom to experiment and brainstorm concepts. Others she hired included Heather Cooper, Tina Holdcroft, Barbara Klunder, Tom McNeely and Muriel Wood.

Born in Chatham, Ont., on Sept. 16, 1928, Margaret Jean Stewart was the eldest of five children. She described her mother as a strong woman; her father was seldom home because he was stringing telephone lines across Ontario. During the Depression, there was no access to art, and magazines were too expensive, so comic strips were her first artistic influence.

When she was 12, the family moved to North Bay where she read every art book in the public library. A bit of a tomboy, Marg also played baseball for the city’s women’s league and, at 15, worked in a sign shop – her first graphic-arts position. She entered Toronto’s Central Technical School in about 1947, waiting tables to support herself. Illustration was her favourite subject, taught by Virginia Luz; other teachers were Doris McCarthy and war artists Carl Schaefer and Charles Goldhammer. Here, Ms. Stewart won the girls’ scholarship (Robert Bateman, now a renowned wildlife painter, won the boys’).

Not all the recognition she received was so helpful. “Robert Ross taught life drawing. He bought me my first beer at the Brunswick [House tavern]. I was told later that he was grooming me for his next mistress but I would have been oblivious to that – and then I met James.”

Dazzling James Hill was to become Canada’s most successful illustrator of the period. But not everyone was impressed. “The teachers were absolutely furious when they heard I was marrying Jimmy. Charlie Goldhammer was so mad he was spitting. … They knew I would probably submerge my talents to encourage James’s, which was exactly what happened. I cannot blame anyone but myself; I did it willingly. What a dummy.”

In fact, in her first art director position, Ms. Stewart gave James Hill a big break: the December, 1952, cover for Canadian Home Journal. Ms. Stewart had landed a job there initially as a low-paid intern, then assumed the mantle when art director Nancy Caudle left. Even at the young age of 24, Ms. Stewart’s forthright manner and high standards were evident. In 2004, illustrator Will Davies reminded her that when he had brought her his best effort, she had remarked, “Well, it’s not Robert Fawcett but it will do.” Mr. Fawcett was a renowned British-American illustrator who had begun his career in Winnipeg, while Mr. Davies was just starting out. “I was very young,” Ms. Stewart ruefully reflected. Mr. Davies’s career was recently celebrated in a hardcover biography.

Unfortunately for Ms. Stewart, the enterprising Jack Kent Cooke purchased the magazine and installed a new male art director – and she reverted to being an assistant again. “I let them flounder,” she said, then left in October, 1953, to become a housewife and mother. For the next six years, she and her husband lived on the outskirts of Toronto, where she had to pump and heat well water and make the family’s clothes, including diapers: “I did everything, I mean everything, so James could have full days in the studio upstairs.” Despite the isolation, she started a greeting-card business, illustrated cookbooks for Chatelaine and made modernist quilts, which were featured in Canadian Homes magazine.

In 1960, she insisted on moving back into town, hoping to rejoin the work force. With Mr. Hill’s reputation on the ascendancy, the couple attended Saturday night parties that included photographer Arnaud Maggs, poster designer Theo Dimson and graphic designer Jim Donahue.

Margaret Stewart stands between two of her creations: a brilliant geometric pattern (background) and a fiercely glowering lion that was designed by her husband, illustrator James Hill, as a wall-hanging for a child's room.Canadian Homes

In 1963, she and James Hill separated. Finding financial dependence on Mr. Hill too precarious, she landed a job assisting art director Gene Aliman at The Globe Magazine.

“I like to think he hired me because I could do the work and had experience, but I was also aware he was attracted to me, which I ignored. When he left a year later I was very happy because I felt I was ready to do the job, which proved to be true,” she wrote. But a month later, he returned and pressured her to give him his old job back. Reasoning that she had more children to support than he did, and that he owned two houses, she refused.

“I think if I had been male he wouldn’t have even tried. I regretted the loss of friendship.”

Ms. Stewart believed she was paid less than a man would have been. In fact, she sometimes waited tables at night to pay for dentist bills and to buy Christmas presents. But, she was quick to point out, she also experienced what she called “reverse discrimination,” where her male co-workers took it upon themselves to sign her up for the union without her knowledge. She was not asked to pay union dues, she said, because she was a single mother, yet she still received benefits.

In 1979, Ms. Stewart left The Globe to art direct the beautifully printed Imperial Oil Review, where she could commission more painterly, full-colour art (some of it by Mr. Hill). She also taught magazine design at George Brown College and Centennial College. After retirement in 1988, Ms. Stewart returned to textile arts.

The TV series Mad Men promoted interest in the experiences of women working in visual communication during the 1960s, but Ms. Stewart never personally identified with the show’s characters. “I never slept my way to anything. My figure was 36-26-38, but I didn’t throw it around like Joan in Mad Men. But I certainly wasn’t a Peggy either. I wore pants and a T-shirt, but I also had Gucci dresses in wild patterns,” she said. “The first time I tuned into Mad Men, I had to turn it off right away. It brought back so many memories. I hated those ad guys. Advertising paid more, but I couldn’t stand the hype and falseness of it. For me, editorial work was more ethical, less callous.”

Ms. Stewart, who donated her remains to the Dalhousie University medical research department, leaves her children, Adriane Hill, Aaron Hill, Chris Hill and his wife, Mary, who cared for her in recent times; her four grandchildren; a sister, Pauline Cain; and three brothers, Peter, Bill and Don.

Dr. Jaleen Grove is a historian of Canadian illustration. She interviewed Marg Stewart for her 2014 dissertation and forthcoming book on Canadian illustrators.