Toronto artist Sandra Brewster's photo showing her mother feeding the pigeons in London’s Trafalgar Square in the 1970s evokes an exuberant presence – at the very centre of the Empire – during a period of increased Caribbean migration.Sandra Brewster/Art Gallery of Ontario

The Montgomery Collection is a horde of vintage photographs from the Caribbean acquired recently by the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, including an image of women balancing bunches of bananas on their heads. They are not showgirls, but labourers lined up for a European photographer in Jamaica around 1895. They do not look particularly happy: One gamely attempts a half smile, another scowls, another squints. Maybe it was a hot day and the sun was in their eyes. Or maybe the women resented being choreographed and sensed that the eventual picture would condescend to their race and their work.

Introducing the Montgomery Collection – purchased from the American collector Patrick Montgomery in 2019 – to contemporary Toronto audiences is going to take some mediation. Julie Crooks, the AGO’s new curator for the art of global Africa and the diaspora, has come up with a big and bold intervention. In Fragments of Epic Memory, Crooks uses the photographs, laid out in large glass-topped display tables, as the backdrop for an exhibition of modern and contemporary Caribbean art, a rich array that provides a retort of sorts to the limited images of sugar cane workers, market ladies and packet boats.

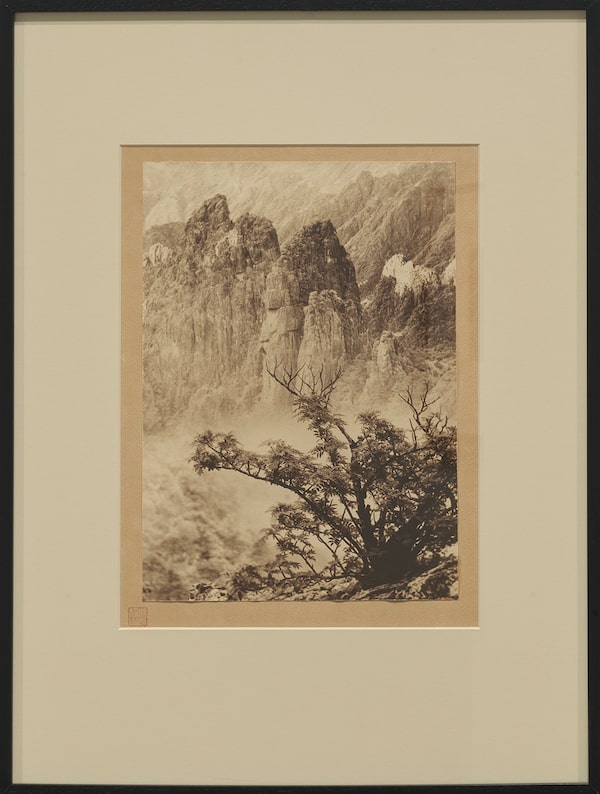

In Majestic Solitude, a mountain landscape from 1934, Chinese photographer Lang Jingshan cleverly reproduces the multiple-point perspective of Chinese brush painting.Paul Eekhoff/Solander Collection

The Montgomery photographs are a rare record of life in the Caribbean from about 1840 to 1940 – post-emancipation to the dawn of post-colonialism – and they include many images of the islands’ workers, as well portraits and even passport photos. Crooks groups them into broad themes: the plantations, the ports, the landscape, the photographer’s studio.

The reality, however, is that these are photographs of people of colour – the Caribbean’s Black population and its many South Asian immigrants – taken by white photographers. Many of the photographers are unknown; a handful are named. They were often itinerant or at least transitory, but were mainly European commercial photographers selling tourist views and studio work. The subjects show agency – there is no shortage of proud portraits – but it is not necessarily their view of themselves, their surroundings or their history.

For that, you can turn to the walls surrounding the photo tables, where a survey of 20th- and 21st-century art by Caribbean and diaspora artists is displayed. It’s a fascinating collection, beginning with 20th-century works that question whether the Black artist can accept modernism’s supposed neutrality. There’s a spectacular yellow canvas from 1970 by Guyanese-British artist Frank Bowling, which you might take as pure colour-field abstraction were it not for the title, Middle Passage, a reference to the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Faint, ghostly figures of Black bodies are tossed about in the centre. Similarly, in Mayombe (1962), a monochromatic canvas of surreal geometric figures, the Cuban artist Wifredo Lam upstages the faux-primitivism of modern art, basing his painting on actual Afro-Cuban spiritual practices.

The women balancing bunches of bananas on their heads are not showgirls, but labourers lined up for a European photographer in Jamaica around 1895.Art Gallery of Ontario

When it comes to recent work, the exhibition features some particularly impressive video art including, as a massive centrepiece, Black Bullets by Trinidadian-Danish artist Jeannette Ehlers. In this 2012 piece inspired by the 1791 slave rebellion that founded Haiti, a line of Black schoolchildren gradually disappear into their mirrored images, marching into a blue sky as though submerging themselves in water. The Jamaican Internet artist Peter Dean Rickards (who was living in Brampton, Ont., at the time of his premature death from cancer in 2014) is represented by Proverbs 24:10, in which two dancing youths perform in slow motion, their bodies becoming fluid, to a soundtrack provided by a sorrowful Nick Cave tune. It’s an arresting work that positions the men’s hip street moves as something eternal and tragic.

The list of engrossing art goes on, including Paul Anthony Smith’s manipulated carnival photography, in which he punctures the photo paper to create a stippled effect that echoes the hyper-decoration of the dancers’ costumes, and Ebony G. Patterson’s …three kings weep…, a large video triptych of three Black men clothing themselves in vibrant floral shirts contradicted by the tears running down their cheeks. After a certain point, you have to ask whether we need the historic photographs as the pretext for an excellent exhibition of contemporary art by the Caribbean diaspora. Why not just cut to the chase?

A handful of artists do more obviously continue where the Montgomery Collection leaves off, providing a photographic social record. The show includes, for example, several of Vanley Burke’s iconic images of Caribbean Britons in the 1970s and Robert Charlotte’s 2014 photographs of the Garifuna people of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. Toronto artist Sandra Brewster, who is of Guyanese extraction, straddles the two modes, documentary and artistic: Her monumental enlargement of a photo showing her mother feeding the pigeons in London’s Trafalgar Square in the 1970s evokes an exuberant presence – at the very centre of the Empire – during a period of increased Caribbean migration.

Coincidentally, Brewster’s work also shows up at a current exhibition at the Royal Ontario Museum. Breaking the Frame is a selection of work from the Solander Collection of alternative photography based in California and Oregon. It’s an eclectic display that suggests a diverse and democratic history of the medium, starting with a daguerreotype of the 1840s showing a print of a painting by Raphael, produced by Madame Gelot-Sandoz, one of history’s first female photographers. It continues with some early experiments with colourizing and multiple exposures, a variety of 19th-century images by Chinese photographers and the work of several feminist photographers of the late 20th century.

If you can ignore the didactic tone set by guest curator Phillip Prodger – wall texts repeatedly exhort the viewer to think about this or imagine that – there are many off-beat delights. In Majestic Solitude, a mountain landscape from 1934, Chinese photographer Lang Jingshan cleverly reproduces the multiple-point perspective of Chinese brush painting. In 1944, Dorothea Lange, one of a handful of famed American photographers included here, catches a couple in a trailer park at the moment of an argument. In the late 1960s, the Mexican photographer Armando Salas Portugal would not reveal how he made his images of mysterious swirling masses, which he claimed were photographs of his thoughts.

In Fragments of Epic Memory, Julie Crooks uses three photographs, laid out in large glass-topped display tables, as the backdrop for an exhibition of modern and contemporary Caribbean art.ORIOL TARRIDAS/Monique Meloche Gallery

Brewster’s image is the last in a collection of about 100; it shows a Black woman’s face blurred by motion, the print enlarged to portrait size but creased and worn, and it leads back to a consideration of the Montgomery Collection. Brewster is one of many contemporary artists who investigate photography’s power to define, to reveal and to hide. As the AGO continues to wrestle with the Montgomery legacy in future exhibitions, a more narrow emphasis on how these images fit in a history of the medium may yet prove useful.

Fragments of Epic Memory continues at the Art Gallery of Ontario to Feb. 21, 2022; Breaking the Frame continues at the Royal Ontario Museum to Jan. 16, 2022.

Kate Taylor

Kate Taylor