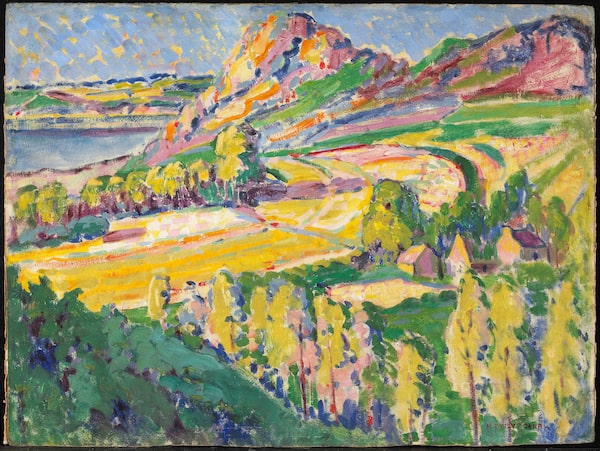

Clarence Gagnon's Old Houses, Baie-Saint- Paul.Handout

Before the Group of Seven and Tom Thomson there was … what? Well, it turns out quite a lot, actually, from fabulous Indigenous art that went back thousands of years to an unfortunately little-recognized school known as the Canadian Impressionists, who came a generation before the legendary Group of Seven was founded in 1920.

They were men and women who travelled to Europe, most often Paris, to study art and began to paint in a modernistic fashion made famous by the likes of Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Not for them the religious and mythological scenes: They wanted to paint contemporary life with an emphasis on light and its changing qualities.

Tagged “Group of Who” several years ago in this newspaper by arts writer James Adams, the Canadian Impressionists somehow became lost in time.

Consider them found again in 2022. On Feb. 9, after two frustrating delays caused by pandemic restrictions, a special exhibition celebrating their achievements will finally open at the National Gallery of Canada.

Called Canada and Impressionism: New Horizons, 1880-1930, the exhibit will feature 108 works by 36 artists, including James Wilson Morrice, Maurice Cullen, Helen McNicoll, Clarence Gagnon, Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté and even Emily Carr and several of the Group of Seven, who began painting as Impressionists.

(Because of continuing capacity limits in Ontario, visitors are advised to book their tickets in advance through gallery.ca.)

A slightly different version of the exhibition has already had considerable success in Europe, where it opened in 2019 to rave reviews in Munich, Germany; Lausanne, Switzerland; and Montpellier, France. German crowds were so enthusiastic they lined up to get into the Kunsthalle, with more than 100,000 taking in the Canadian Impressionists. Unfortunately both the Lausanne show and the Montpellier one were forced to close after six weeks owing to new waves of COVID-19.

Maurice Cullen's The Ice Harvest.NGC/National Gallery of Canada

“Wherever the exhibition travelled,” says Ash Prakash, the Toronto-based art collector who serves as the exhibition patron, “the overwhelming reaction of the German, the Swiss, the French art critics was, ‘How did we not know of this group?’” (The AK Prakash Foundation was a major contributor, along with other partners, to the tour.)

The National Gallery’s senior curator, Katerina Atanassova, fell in love with the works of the Canadian Impressionists when, with the assistance of Prakash, she curated a major exhibition of the works of Morrice. The 75-year-old Prakash once donated dozens of Morrice paintings to the National Gallery and has long been of the opinion that Canadian artists such as Morrice, Thomson and Carr should be as revered as Monet and other European masters.

“That experience set me on that period in Canadian art,” says Atanassova, who was born and raised in Bulgaria. “My objective was to put Canadian art in a global context. … There were so many incredible artists that were long forgotten.”

“It’s absolutely true to say that most Canadians think of the Group of Seven as the canon, or the core group of artists,” says Sasha Suda, National Gallery director and chief executive officer. “I don’t know how often people think about what came before them.”

And yet, from the early 1880s through to 1930, Canadian Impressionism was the major form of art in this country.

“Those artists were so daring in those days,” Atanassova says. Several believed they had to travel overseas to learn from the best teachers. “Just going abroad took nerve. There might be communal pride in their accomplishments, but little national or international attention. We tend to only acknowledge an artist after they’ve been accepted abroad.”

Snow II by Lawren S. Harris.Family of Lawren S. Harris

The project was conceived, Suda says, as something that could teach others the importance of Impressionism in Canada. “We commonly think of France as the genesis of Impressionist art. It was, but it is a movement that very much had roots here in Canada, as well.”

Prakash, a native of India, was a rising young star in the Ottawa bureaucracy – he would go on to serve in both the Privy Council Office and the Prime Minister’s Office – when he went to work for UNESCO in Paris in the late 1970s.

“I frequented the galleries every chance I could,” he says, “and I discovered the magic of light.”

On his return to Ottawa, he began researching the Canadian artists who had brought Impressionism back to Canada. “They kept painting in a style even though there was no market for it at the time,” he says. “It just blows me away – it was a passion they just had to exercise.”

Eventually, decades later, there was a market. Prakash himself ended up a collector after paying $40,000 for a small “pocket painting” of a Venice scene by Morrice. “I had no business buying it,” he says. “It just took my breath away. I could barely afford it, but I did it.”

Atanassova’s intense research – a 296-page art book with multiple essays accompanies the exhibit – has led to new thinking on these artists. While Hamilton’s William Blair Bruce is often named the first Canadian Impressionist, Frances Jones did the first important painting in this style, an 1883 portrait of a room in her family’s Halifax home. In the Conservatory belongs to the Nova Scotia Archives and is considered too fragile to travel.

If there is one delightful surprise in this show it is the large number of female painters included. The Group of Seven are so dominant in Canadian art history that the impression is sometimes of an old boys’ club.

James Wilson Morrice's The Pond, West Indies.Brian Merrett/The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

“The women came from coast to coast,” Atanassova says. “Frances Jones came from Halifax. Helen McNicoll came from Toronto. Emily Carr and Sophie Pemberton from Victoria.”

Essayist Anna Hudson, who teaches art history at York University, writes in the exhibit’s book that the “Woman Question” was a great debate of the day. Painters such as McNicoll, Pemberton, Jones and others “celebrated their modernity” through their paintings, often charming scenes of children and mothers who represented the “New Woman.”

The debate about the role of women in society even led humorist Stephen Leacock to discuss the issue in the pages of Maclean’s: “The vacuum cleaner can take the place of the housewife. It cannot replace the mother. … When women have the vote, there will be no more poverty, no disease, no germs, no cigarette smoking and nothing to drink but water.” It would be, he added, “a gloomy world.”

But there is no gloom here. Only light and fresh air.

The one concern, of course, is the pandemic. Canada and Impressionism: New Horizons has already been delayed once.

“It was slated to open smack in the middle of the early months of the pandemic,” Suda says. “But it’s amazing that we have had great visitorship through this. Our attendance is almost prepandemic. We have been seeing 80 per cent of our pre-COVID attendance.”

Suda also points out that even if the Ontario government restricts the gallery to 50-per-cent capacity, the building is so large that it rarely gets to that level during the winter months. “We’re blessed to have such a huge space,” she says.

“I hope so much that we can get the whole exhibition in as planned,” Atanassova says. ‘It’s intended to go until June 12. It’s such an uplifting event. At this particular time of year, it’s sunshine.”

As Prakash discovered in Paris more than 40 years ago, Impressionism art is “the magic of light.”

Emily Carr's Autumn in France.NGC/National Gallery of Canada

Editor’s note: In the Conservatory will not be in Ottawa for the new exhibition, which begins Feb. 9. This version has been updated.

Sign up for The Globe’s arts and lifestyle newsletters for more news, columns and advice in your inbox.