In 1857, Victorian photographer Oscar Rejlander exhibited what is still considered his most important work. Using 32 different negatives, some of single figures, some of small groups, he created the monumental Two Ways of Life (Hope in Repentance). A bearded old man stands at the centre of the composition, the apex of a low triangle. On one side, he loses a wayward son to figures of debauchery, most of them represented by naked women; on the other, he encourages an upright son toward sober allegories of marriage, charity and learning. It’s not hard to see who in this equation is going to have the most fun – although that was surely not Rejlander’s point.

The photograph, represented in two different versions in the Rejlander retrospective organized by the National Gallery of Canada (NGC), was controversial in the artist’s own day. It was one thing to portray nudes as allegorical or historical figures in paintings, quite another to show the naked model’s actual flesh through the new medium of photography. The artistic community was also divided over combination photography, questioning whether the manipulation of the negatives was truthful.

Today, we would recognize any amount of manipulation as the art photographer’s prerogative and readily accept the nude as a subject, but the preachy Two Ways of Life is a prime example of why Rejlander remains a figure of more historical than aesthetic interest. There is no denying the technical mastery the photographer flourished as he assembled all these negatives into a seamless whole – and there’s no sympathizing with the work’s simplistic moralism.

Mary Constable and her brother, an 1866 albumen silver print by Oscar G. Rejlander.The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Rejlander’s campaign to elevate photography to the level of art by using it to reproduce traditional categories of painting, such as genre, allegory or history, turned out to be a dead end. It swam against the currents of art-making that were already flowing toward spontaneous observation, a task to which photography was ideally suited. Even within his own lifetime, Rejlander’s insistence on storytelling over objective record meant that his work was falling out of favour and nothing that has happened since has done much to change that. This retrospective, a massive task of assembling works from multiple lenders undertaken by NGC photography curator Lori Pauli, is the first major survey of the artist’s career.

And yet, for all that Rejlander’s subjects now seem quaint, his insistence that photography was something more than, or different from, a documentary record, and his arranging of his models and his negatives make him the father of art photography – and a figure of interest in an age where digital manipulation and social messages are commonplace in all the visual arts.

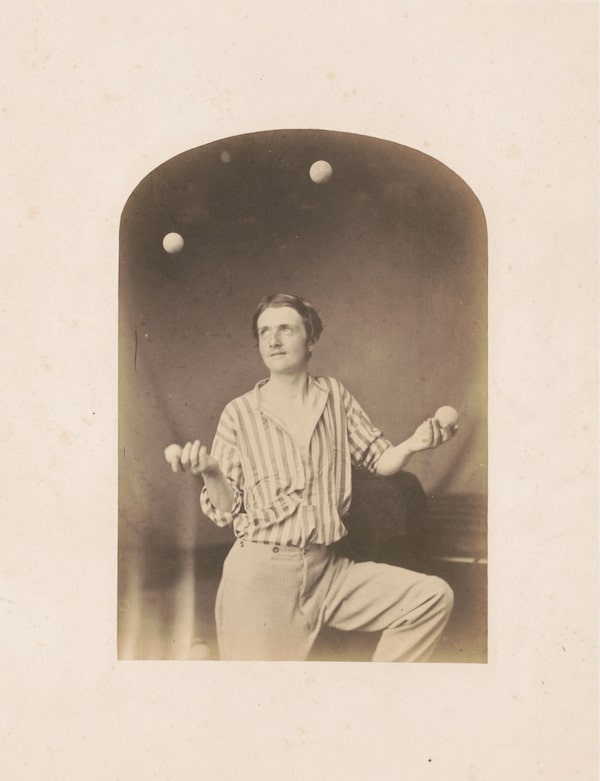

The Juggler, circa 1855-61, an albumen silver print by Oscar G. Rejlander.Courtesy of the Library of Congress/Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Rejlander trained as a painter in Sweden – there are a few small drawings here from his very early career – and immigrated to England in 1849. A portrait painter, he discovered photography in 1852, taking a few courses including some brief instruction in the wet-plate collodion method that was revolutionizing the cumbersome medium. His early genre pictures, such as Jane and Joe, Saturday and Jane and Joe, Sunday – showing a working-class couple doing the dishes one day and dressed in their best clothes the next – were highly popular with the public and now provide a document of Victorian life from wash day to tea time.

Early on, he saw how useful photography could be to the painter, especially for anatomical reference, and sold fellow artists his figure studies. He was an innovator in the darkroom, full of tricks to simplify processing, and a master of the multiple negative technique that had been invented by the French photographer Hippolyte Bayard, using it often to provide a backdrop for subjects shot in the studio. Two Ways of Life seems primarily to have been intended as a grand technical exercise – in defending it, Rejlander spoke about the moral aspect only in passing – but after its mixed reception, he increasingly turned to portraiture, from which he had always derived a good income. A commission from Charles Darwin, who asked him to record human expression, proved a life saver and offers another intriguing historical aspect to this show.

But it is the straight portraits of the same late period that will really strike a chord with the contemporary viewer, because of the way Rejlander’s humorous depiction of character and expression in genre subjects can now depict psychological atmosphere. There is no veil separating us from the spontaneity of his Portrait of A Woman seated at the piano or the delicacy of the familiar portrait of Charles Dodgson a.k.a Lewis Carroll. And the intensity with which Mary Constable and her brother stare, apparently into a flickering fire, is arresting. (The siblings were probably shot outdoors in broad daylight.) Here, finally, Rejlander’s love of humanity and his technical accomplishment seem to complement each other, rather than compete for our attention.

Oscar G. Rejlander: Artist Photographer is on view at the National Gallery of Canada until Feb. 3, 2019.

Kate Taylor

Kate Taylor