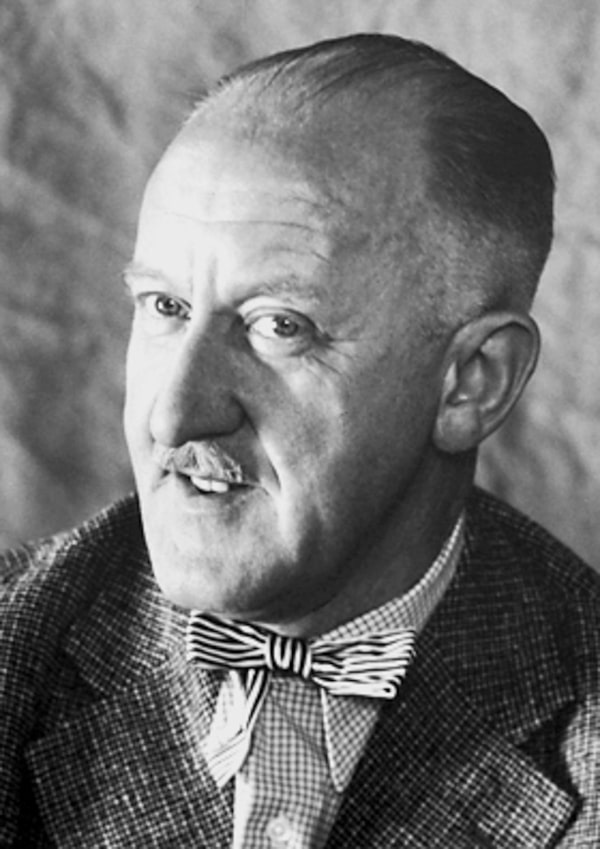

Icelandic author Halldor Laxness in 1955.Alamy

In 2016, the Musée d’art contemporain in Montreal exhibited three large video installations by Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson. One of these, called World Light – The Life and Death of an Artist, depicted a month-long, non-stop performance of an attempt to film a late-1930s series of novels by Icelandic author Halldor Laxness.

A year earlier, Kjartansson and 20 collaborators had occupied a Viennese gallery for four weeks, filming the artist’s 80-scene screenplay of Laxness’s World Light, as well as all of the rehearsals, multiple takes, set building and costume making that the cast did in front of gallery visitors. This was the video record shown in Montreal, in a four-screen display that bombarded the visitor with simultaneous views of different parts of the performance. Kjartansson also presented Montrealers with a 50-minute, impressionistic and unpeopled staging of World Light, which he called “an impossibly big story on beauty,” and “my Bible.”

Not many artists devote so much energy to celebrating other artists. I decided I had to find out more about Laxness, beyond the crossword-puzzle clue that he won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1955.

Soon afterwards, in a Toronto bookshop, I spotted, and bought, a copy of Wayward Heroes, another hefty Laxness narrative from 1952. It’s about a poor, 11th-century ruffian who vows to become a true Icelandic hero, which to him means killing as often as possible and accepting help from no one. A friend offers to record his bloody deeds in verse, in the tradition of skaldic poets who celebrated the conquests of warriors and kings, and were often paid by those heroes to do so.

The style of writing is blunt, descriptive and earthy – a parody, in fact, of the heroic sagas which Laxness aims both to memorialize and debunk. His unstated premise is that a hired eulogist is really just a propagandist. Much of Wayward Heroes is a ferocious retelling of the story of Olaf Haraldsson, the real-life man of war who battled his way to the throne of Norway in 1015, and was canonized after his death as St. Olaf.

In Laxness’s telling, Olaf is an intolerant, self-serving butcher. Much of what he and his mercenaries do would qualify, nowadays, as war crimes. Rather than signal condemnation of Olaf’s deeds, Laxness recounts them with a relish that often borders on the comic. His fictional pauper-warrior bumbles along in Olaf’s train, lost in fantasies of heroism like a belligerent Don Quixote. Wayward Heroes is the blackest tragicomedy I’ve ever read, and a brilliant, postwar parable about murderous deeds done in the name of some higher principle.

After that, I read Independent People, Laxness’s 1934 novel about a poor crofter with a mania for self-reliance. The novel opens with the tale of a wizard king and his acolyte, a woman who feeds on human blood and marrow, and who lives on after death as a malign spirit. Bjartur, the poor crofter, settles in a place said to be cursed by this spirit; but rather than try to placate her in the customary way, he spits on her cairn, and vows allegiance to nothing but his own freedom.

Laxness’s unvarnished account of Bjartur’s hard-scrabble life alternates with passages of radiant pastoral beauty. While knitting, Bjartur’s second wife tells her son elfin legends, including one about a poor foster child who has a religious epiphany at a Fairy Rock. Laxness then writes: “From the white heaven of mist where the sun was hidden like a delightful promise there dropped into her hair a thousand precious glittering pearls as she told her stories. She pursed her lips at the end of each solemnity, almost with adoration, as if they were sacred chronicles. Gently she smoothed the loops on her needles; the landscape was shrouded and holy.”

Bjartur pursues his self-reliance with brutal efficiency, insulting his neighbours and trampling on his family’s feelings. He nearly dies of exposure while trying to find a lost sheep in winter, at one point hitching a fantastic ride on a terrified bull reindeer. Bjartur’s sole indulgences are coffee and poetry, the more arcane and rule-bound, the better. His undoing comes with the sudden economic boom caused by the First World War, and the bust that ensued after the armistice.

“Laxness’s heroes never triumph, yet failure never completely destroys them,” critic James Fadiman wrote in a 1990 essay. “He writes not about hope but about the striving that continues after hope has been abandoned.”

The first English edition of Independent People in 1947 was a huge success in the United States, as a Book of the Month Club selection that sold nearly 450,000 copies. But Laxness’s socialist beliefs and ties to the Soviet Union, which he visited twice in the thirties, marked him out for attention by the FBI and State Department. It was the period of the Red Scare and the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Laxness sealed his own fate with The Atom Station, a 1948 satire about Icelandic politicians selling out to American wishes to establish a missile base on the island. In 1953, he accepted the Stalin Prize for literature.

His American publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, issued no more of his novels, not even after he won the Nobel in 1955. The New York Times recorded that event under the headline, "Anti-American Writer Wins ’55 Nobel Prize.” Laxness’s later novels appeared in translation only in England, and only from small presses.

Random House reintroduced Laxness to English readers in 1997, the year before he died at the age of 95, with a Vintage Classics reissue of Independent People. Five other titles followed in the same series. That’s a fraction of his prolific output, which also includes plays, poetry and stage adaptations of his novels.

My favourite so far is World Light, which is based on 20 manuscript volumes by an obscure Icelandic folk poet about his life and work. Laxness’s hero Olaf Karason is another rural pauper, whose miserable existence is brightened by his belief that he will become a major poet. The novel details with clarity, and sympathy, the gap between his sordid daily life and his faith in a beauty which is almost too powerful to be endured.

“Every transgression is a game,” Laxness writes, “every grief easy to bear, compared with having discovered beauty; it was at once the crime that could never be atoned, the hurt that could never be assuaged, and the tear that could never be dried.”

In his Nobel acceptance speech, Laxness thanked his grandmother, “who taught me hundreds of lines of old Icelandic poetry before I ever learned the alphabet,” and who encouraged him to love and respect “the humble routine of daily life.” In those lines is a rough summation of his work as a novelist, which resonates with echoes of Iceland’s rich poetic heritage, and with the highly textured realism of a socially conscious writer.

Live your best. We have a daily Life & Arts newsletter, providing you with our latest stories on health, travel, food and culture. Sign up today.