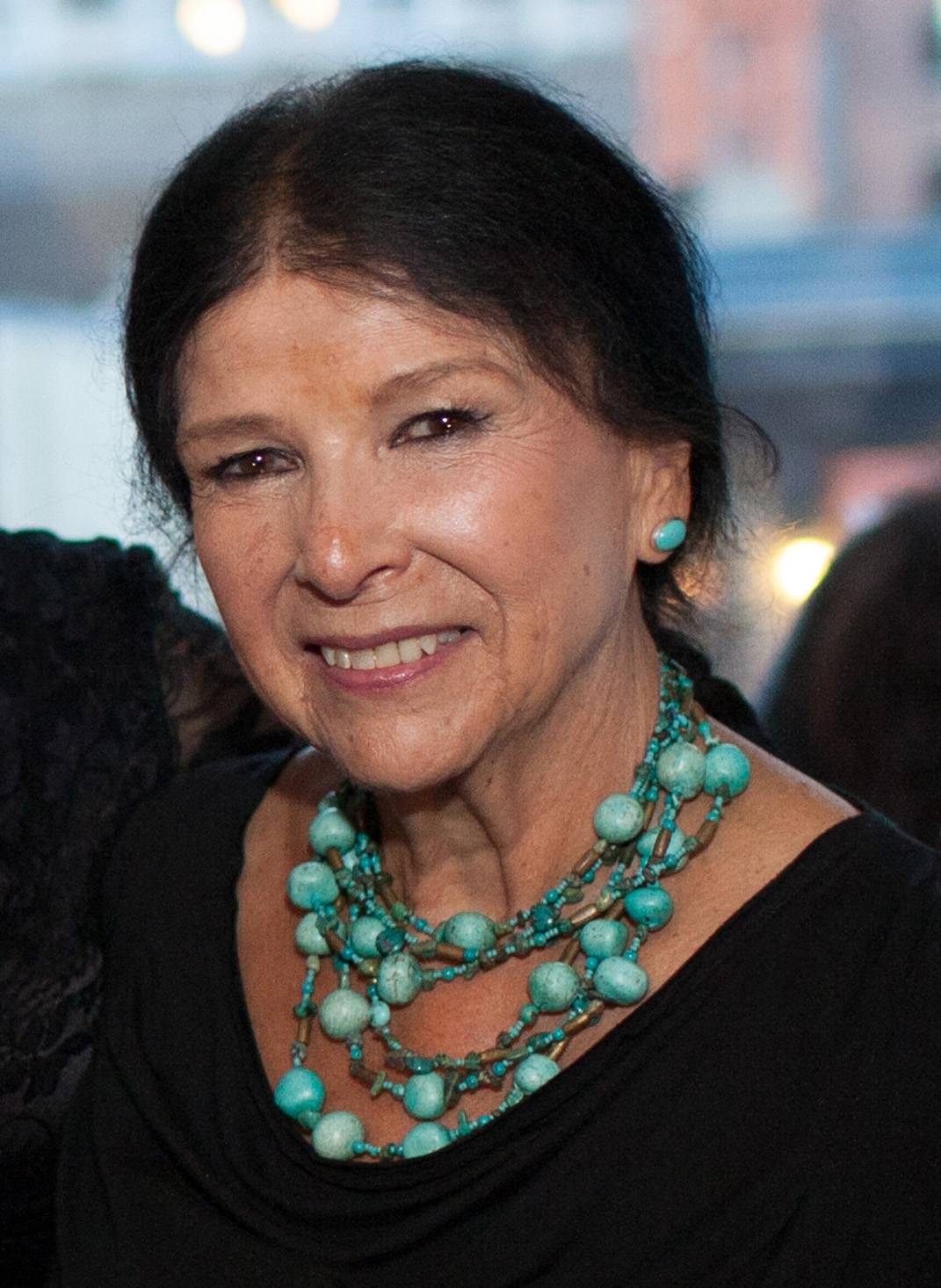

The documentary filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin has visited hundreds of Canadian schools over the years. As a young woman of Abenaki descent, she worked as a performer, taking traditional songs and stories across the country in an effort to give both Indigenous and non-Indigenous children a positive image of Aboriginal culture, and she has continued visiting schools with her documentaries. But she had never been in a place as impressive as the Helen Betty Osborne Ininiw Education Resource Centre at the Norway House Cree Nation in northern Manitoba.

"The children are so happy; they love their school. It's so encouraging. The children are kings there," she said in a recent interview as she prepared to both launch her 50th film, Our People Will Be Healed, at the Toronto International Film Festival and celebrate her 85th birthday. "It's a model for other communities."

As part of the pioneering Frontier School Division that covers northern Manitoba, the provincially funded school teaches the Cree language, Indigenous studies and a lot of fiddle music alongside the usual classes in math, science and English – and it was the starting point for Obomsawin's new film, the latest in a long career making point-of-view documentaries from an Indigenous perspective at the National Film Board of Canada.

"The biggest reason is to show how possible it is to change the system of education and make it healthy," she said about a film that then branches out to reveal how all of Norway House is successfully battling the legacy of the residential schools. "The root of it all is love of the children, love of the people. And to pay attention to what our ancestors went through and these traditions. You take the best of it and apply it. My God, there has been so much suicide and such a history of alcohol and drugs, but there is a strong movement with young people saying no … a strong movement of young people helping other young people who still have problems."

Our People Will be Healed reveals how Norway House is successfully battling the legacy of residential schools.

Obomsawin had originally visited Norway House to document the story of Jordan River Anderson, a local child with a rare muscle condition who spent the entire five years of his short life in a Winnipeg hospital because the provincial and federal governments could not agree who would pay for home care if he was discharged and returned to the reserve. (His story is included in Obomsawin's 2016 film We Can't Make the Same Mistake Twice, which covers the human-rights suit against the federal government over social services for children on reserves, and she currently has a second film, exclusively about the boy, who died in 2005, in production.)

Anderson's death established Jordan's Principle – pay first, argue later – but the social-service issues don't make happy stories. Yet when Obomsawin visited Norway House, she found, as is often the case in a documentarian's life, that there was another story waiting there, too, that of the school and of the community's efforts to reground itself in tradition. Her film ends in a poignant moment where people gather to revive the sun dance, a traditional ritual of sacrifice and prayer that was largely suppressed by the federal government until 1951, but kept alive through underground practice. Unusually, Obomsawin was allowed to film some of the ceremony – although she kept a discreet distance during the shoot.

"I was touched that I could film there, but I would not be aggressive. I felt you have to restrain yourself, but at the same time I want young [Indigenous] people to know that it's there and it's theirs, and they would be welcome."

And so, Our People Will Be Healed – the title is a quote from a person interviewed in the film – marks a particularly optimistic moment in Obomsawin's long career.

"I really think we are going somewhere where we have never been before. I don't even know how to express how rich it is. It is more than hope, it is higher than that," she says, speaking of both Indigenous people's resurgence and settlers' increased sensitivity. "I am so thankful I am still alive to see the change. Everywhere I go, I feel respect."

Obomsawin, who has no plans to retire as long as she is healthy and has several more films in the can, feels she was chosen to live and destined to work: She almost died at six months and her parents lost four other children in their infancies; her father died of tuberculosis at the age of 42. Born in New Hampshire, Obomsawin grew up on the Odanak reserve near Trois Rivières, Que., but her family moved into town when she was 9. She remembers that in those years the school books taught her classmates that she was a savage whose people scalped their enemies.

"The education system was designed to create hate towards First Nations, Inuit and Métis people … Every time it was 'histoire du Canada,' I knew I couldn't get home without getting beaten up," she recalls.

‘The education system was designed to create hate towards First Nations, Inuit and Métis people,’ Obomsawin says. ‘Every time it was ‘histoire du Canada,’ I knew I couldn’t get home without getting beaten up.’

National Anthropological Archives

She began her career determined to change the narrative with her work as a singer, and was fundraising for a swimming pool on her reserve in the early 1960s when her crusade was filmed by the CBC and she came to the attention of producers at the NFB. In 1967, she signed on as a consultant but felt she was mainly being used to gain access to reserves. Instead, she began working on educational materials, producing the NFB filmstrips that used to be shown in schools, and made her first NFB short, Christmas at Moose Factory, about children's experience of the holiday in that northern Ontario community, in 1971.

Since then, she has produced films at the rate of about one a year and is still probably best known as the filmmaker who stuck it out for the entire 78 days of the blockade at Oka, Que., in 1990, producing her classic Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance.

Asked if that dispute triggered by the town's desire to expand a golf course into traditional Mohawk territory could happen today, Obomsawin warns that the land claim was never fully resolved and there are further plans for development in the area. But more generally, she feels the relationship between First Nations and other Canadians has altered significantly.

"With reconciliation, Canadians have learned a lot of that history; you have a feeling that they are listening to you. That they want to know and that they want to see justice," she said. "I have a great feeling."

Our People Will Be Healed screens at TIFF on Sept. 9, 11 and 15 (tiff.net/festival). It will also screen at the Calgary International Film Festival, which opens Sept. 20, the Vancouver International Film Festival, which opens Sept. 28, and at the imagineNative Film and Media Arts Festival in Toronto, which opens Oct. 18.