Darwyn Cooke’s masterwork DC: The New Frontier brought his fascination with the United States’ Camelot age to the fore.

DARWYN COOKE/DC ENTERTAINMENT

Much as you'd expect from someone who made a living bringing superheroes to life on the page, Darwyn Cooke was not afraid to stand up for what he thought was right. He spoke his mind about the dark state of comics franchises and in the end managed to breathe new life into the medium, redesigning classic characters and imbuing his work with the optimism of bygone days.

After working for more than 30 years in animation, comic books, graphic design and illustration, which included characters from Batman, Wonder Woman and Lois Lane to Wolverine, Parker, the Spirit and The Watchmen, the virtuoso Canadian artist and storyteller died at his home near Tampa, Fla., on May 14 at the age of 53. The cause was lung cancer.

Although he was a proud Canadian, it was John F. Kennedy's Camelot – with its Cold War tensions, social upheaval and cool aesthetics – that held an enduring fascination for him. His masterwork

DC: The New Frontier (2004) sets the origins of the Justice League and the characters of the DC Silver Age into a powerful narrative set in the America of that era. The six-issue comic book series, named for the JFK's 1960 Democratic nomination acceptance speech, would win Mr. Cooke the first of his 13 Eisner Awards, the industry's most prestigious accolade, and he won many of its others – Reubens, Harveys and several Shusters, the Canadian comics awards named for the Canadian co-creator of Superman. (When the Justice League: The New Frontier animated movie adaptation came out, it was nominated for an Emmy.)

His dynamic illustration, panel design and thoughtful approach to writing transcended mere nostalgia, whether he was telling hard-boiled stories of anti-heroes or exploring heroism through superheroes. Though whenever it was suggested to Mr. Cooke that he was an auteur he'd reply, "I'm more like John McTiernan," the director of Die Hard, one of his favourite movies. "That's the kind of creator he thought he was," his friend Michael Cho says. "An entertainer."

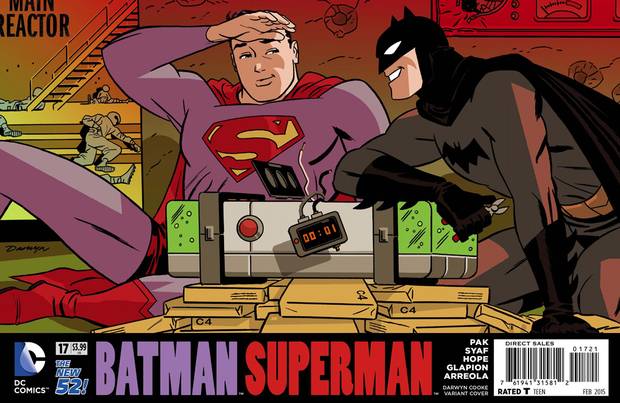

One of several ‘widescreen’ variant covers Mr. Cooke did for DC Comics in 2014.

DARWYN COOKE/DC ENTERTAINMENT

Darwyn Grant Cooke was born on Nov. 16, 1962, to Grant, a construction foreman, and Joanne, an office administrator and homemaker. He was raised in Etobicoke, Ont., with younger brothers Kenneth and Dennis. In many interviews, he said he wanted to work in the comic industry from the age of 13 when, bored while visiting his aunt and uncle in Sudbury, Ont., he had picked up a reprint copy of The Spectacular Spider-Man, studied it and copied it inside and out for weeks. He took art classes at his suburban high school and made a small start in the industry in his early 20s, when he placed a story in DC's New Talent Showcase. But Mr. Cooke would not publish another comic until 15 years later, with Batman: Ego.

Expelled from George Brown College's design program after his first year (he spent more time in college enjoying himself than he did working on assignments, he said), he first swerved into graphic design. While waiting tables at the Madison Avenue Pub in downtown Toronto, he counted among his regulars the publisher and editor of Music Express magazine. One night they mentioned they needed an art director. "So I went out the next day and I bought a copy of the magazine," he told The Comics Journal in a 2007 interview. "Then I took a couple weeks at home using way-old markers and what I'd learned in college, and I redesigned the magazine." He presented it to them and for four years (1984 to 1988) he was the art director (and of its short-lived sister heavy metal publication Metallion), designing pages and overseeing shoots with David Bowie and Robert Plant.

He then worked as associate art director at Flare (and later, briefly, at Chatelaine). Shelley Black, Flare's editor-in-chief at the time, remembers Mr. Cooke as a hip, young guy who was always wearing a black motorcycle jacket. "He wasn't a corporate sort of guy, or like every other mild-mannered art director – he had an edge to him," she said.

For much of the 1990s, he then worked as a creative for Toronto ad agencies such as Doner Schur Peppler and Brotherhood, where he won awards for packaging and TV commercials. His clever and graphic 1960s-inspired advertising sensibility later contributed to his dynamic comics pacing and design, as did the cinema theory and frame composition he absorbed through his love of movies.

Mr. Cooke resisted the pull of comics until an opportunity came along to work on Batman, which had been his earliest comics-related love as the boy who sat riveted to the campy Adam West TV series. After answering a trade ad placed by director Bruce Timm in the late 1990s, Mr. Cooke began drawing the caped crusader as a storyboard artist in the Warner Brothers animation department, later taking a turn as a director on Men In Black: The Animated Series.

Artist Steve Manale became friends with Mr. Cooke when they met in Toronto in those years, while Mr. Manale was still in art school and working at the Silver Snail comics shop, on Toronto's Queen Street West. Mr. Manale began working as an animation assistant and the two eventually shared a studio for several years. Every Wednesday at lunchtime, Mr. Manale says, they'd walk over to Dragon Lady, the nearest comics shop, to check out the week's new arrivals. The store also sold ephemera, including the old Life and Time magazine tear sheets and ads that Mr. Cooke collected to use as period design references.

After browsing Dragon Lady, Mr. Manale and Mr. Cooke would go for lunch, discuss life and talk shop. Soon the Wednesday group expanded to include more young artists. "We were total nerds," friend Michael Cho laughs. "He was, too. He was just the coolest of us. But he was still the kind of nerd who could spot who inked what from the corner of a [Jack] Kirby panel." One day, when their regular waitress overheard them talking about comics yet again, she dubbed them the Superman Club. The name stuck (although when Mr. Cooke was out of town or missed a week, they jokingly called themselves the Jimmy Olson Club).

It was one of the old magazines Mr. Cooke found at Dragon Lady – Look magazine from November, 1954, with Gina Lollobrigida on the cover – that inspired his revamp of Catwoman, with writer Ed Brubaker in 2001.

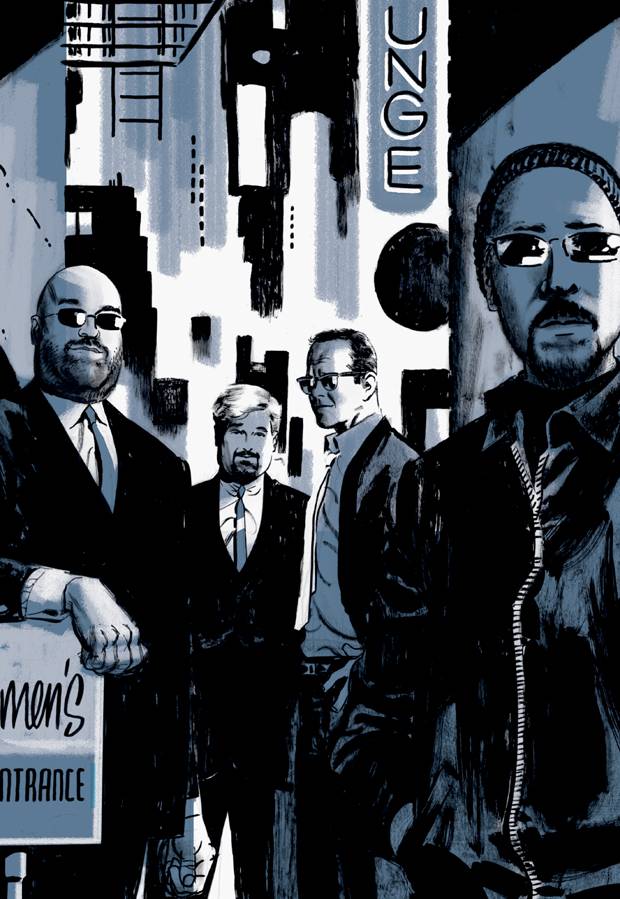

Mr. Cooke, second from right, and writer Ed Brubaker, right, are shown in a portrait used in a deluxe edition of the Parker books. At left are comics journalist Tom Spurgeon and IDW Publishing special project editor Scott Dunbier.

DARWYN COOKE/IDW PUBLISHING

Catwoman's art and stories had turned salacious and as a condition of his participation in the project, Mr. Cooke insisted on redesigning the character; he also made it clear he wouldn't titillate. In biker boots and a modified aviation helmet and goggles, she would be a positive female character – equal parts adventurer and detective, both in the Catwoman comics series and Mr. Cooke's later hit graphic novel, Selina's Big Score, a heist story.

When Mr. Cooke's long-time girlfriend, Marsha Stagg, and their beloved black lab, Bud, moved to Nova Scotia's Eastern Shore in 2005, the Superman Club's assorted artists sent him off in style by drawing a tribute comic. Many of them had inked or collaborated with him in some way over the years, or received job recommendations from him. "Everything he did was in life," artist and friend J. Bone recalls. Aside from an occasional blog post, "he didn't live on social media at all. And I think that goes into why his characters are so good. He hung out and really listened and talked with people." From Nova Scotia, that meant two- and three-hour-long phone conversations, a couple of times a week.

After his Catwoman redesign (the template is still in use today), other projects such as Marvel's X-Statix and work on Spider-Man followed until Mr. Cooke embarked on an ambitious project, later named DC: The New Frontier, involving what he felt was a return to the true origin of superhero stories.

The joy in his work feels different from today's grim and cynical superhero franchises. It was a sincere vision, of superheroes as our best selves. "We drift back and forth in the last three decades between wanting to poke holes in heroes and wanting to celebrate heroes in the comics," says Paul Levitz, the comics writer and long-time editor at DC Comics who was president and publisher from 2002 to 2009. "Darwyn's material was certainly the more cheerier and optimistic," he adds. "It was the superhero flying down smiling the whole time, kind of magic. And he does a really sweet Wonder Woman – you want to meet that gal." The powerful warrior Wonder Woman towers over Superman, as an Amazon should – a detail Mr. Cooke delighted in pointing out.

Mr. Cooke’s art stood apart with its joyous, optimistic tone, like this tableau of DC Comics heroes enjoying a night out.

DARWYN COOKE/DC ENTERTAINMENT/ASSOCIATED PRESS

A seasoned animator but still a relative newcomer transitioning into comics, Mr. Cooke had pitched it as a sprawling, complex story that would involve numerous key DC characters, with a non-linear narrative in the vein of The Limey and Memento. "When the presentation material came in pitching for what ultimately became the New Frontier series," Mr. Levitz recalls, "people aren't usually that good their first day! He was extraordinary. And he had a very personal vision, which not every creative person does. He had a deep and rich sense of the history, and of texture."

Later, DC tapped Mr. Cooke to work on Will Eisner's The Spirit – another good fit, Mr. Levitz says, because "Will always had his tongue planted firmly in his cheek about the heroicness of his Spirit. He was a Cary Grant sort of hero. With a lightness to it and a wit that very few superhero creators who followed could achieve."

In his work and life, Mr. Cooke had a similarly wry sense of humour – sometimes appearing at conventions in the red dress serge tunic and Stetson of an RCMP officer (at WonderCon 2010) or on another memorable occasion (Dragon Con 2009) wearing a plush Winnie the Pooh mascot costume.

Mr. Cooke also revelled in the complex amoral universe of the anti-hero loner of hard-boiled crime fiction. He was especially a fan of the Parker novels, which were set in the 1960s and written by novelist Donald Westlake under the pseudonym Richard Stark. Although it took some work, Mr. Cooke persuaded the author to allow him to adapt the Parker books into graphic novels. Mr. Westlake died shortly before the first, Parker: The Hunter, was published in 2009. Three other Parker adaptations followed.

IDW Publishing special project editor Scott Dunbier worked with Mr. Cooke at DC on The Spirit and was also best man at his Las Vegas wedding in 2012. Because the date fell on Mr. Cooke's 50th birthday, Mr. Dunbier wanted to arrange a special gift, so he contacted Abby Westlake, the writer's widow, with a particular request. She agreed to part with an important artifact. Mr. Dunbier recalls the moment when the groom realized the gift wasn't just any old, clunky Smith-Corona manual typewriter, but one of Mr. Westlake's very own, used to bang out his books. On an otherwise jubilant Vegas weekend it was a teary moment, since the adaptations had been Mr. Cooke's long-time dream project.

Mr. Cooke's recent winters were spent in Florida, a place imbued with fond childhood memories of family vacations poolside in Kissimmee. He also maintained close ties to his hometown, regularly attending FanExpo and the Toronto Comic Arts Festival. Mr. Cooke told Quill & Quire last year that he was planning a new three-issue comic called Revengeance, a noir thriller that would have been his first creator-owned foray. It was set in the familiar 1980s downtown Toronto art scene of his youth.

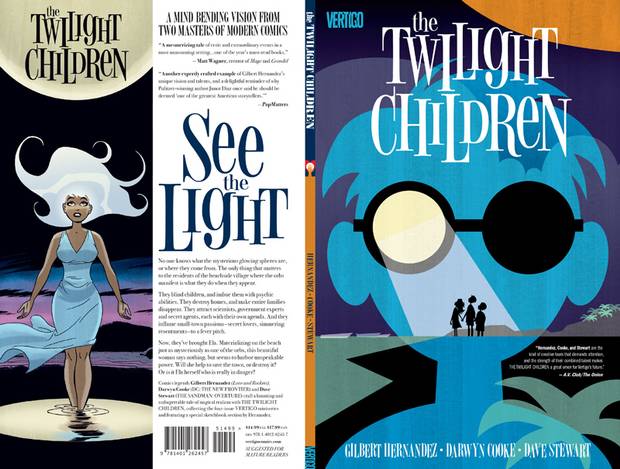

Twilight Children was the last completed Darwyn Cooke project before his death.

DC ENTERTAINMENT

Mr. Cooke's last completed project was The Twilight Children, a science fiction saga co-created with Gilbert Hernandez and in the weeks before his death at his beloved kitschy Florida bungalow, Mr. Cooke was still occasionally drawing covers and reading comics (the very last, the new Mr. A #18, by Steve Ditko). He is survived by his wife, Marsha Cooke, brother, Dennis Cooke, and extended family.

Mr. Cooke admired test pilot Hal Jordan and alter-ego Green Lantern – one of the cornerstones of New Frontier – as much for the character designs as for their heroism. Having recently rekindled his interest in pilots and the space race, Mr. Cooke visited the SpaceX rocket manufacturing and launch facility headquarters in Hawthorne, Calif., with his wife last year. They became enthralled by the idea of space travel and he spoke of little else.

In addition to planning memorials in Toronto and Los Angeles in the coming months, Mr. Cooke's friends and family are hoping to transport his ashes into orbit.

Space, the final frontier.

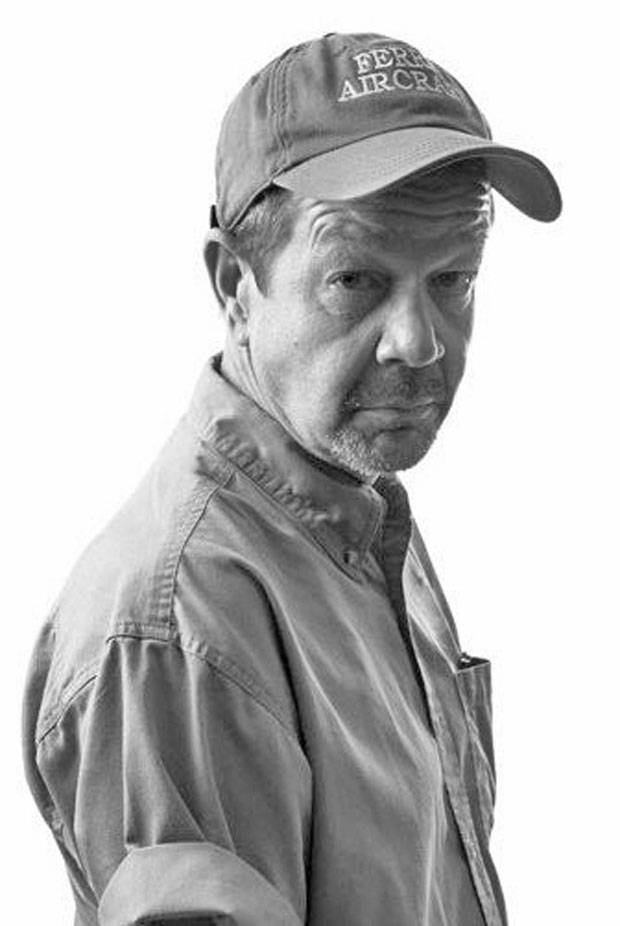

A self-portrait of Darwyn Cooke: He had a vision of superheroes as our best selves.

DARWYN COOKE/IDW PUBLISHING