As readers everywhere put up their feet, sigh and crack the spines of their summer books, let us not forget that these luxurious escapes are the fruits of many years of persistence, labour and stiff drinks on the part of their creators. The Globe and Mail asked four fiction writers to tell the origin stories of their debut novel.

Elizabeth Renzetti: 'I’ve always been fascinated with liars'

I blame it all on Marianne Faithfull, and her drugs. Twenty years ago, I arrived in a Toronto hotel room to interview the singer about her just-released memoir, called, with no strain on anyone’s imagination, Faithfull.

She staggered a little on her high heels; it was after lunch, and lunch consisted of white wine and possibly not much else. She was smoking American cigarettes, and reading Osip Mandelstam, and nursing an abscessed tooth. “Marianne,” called the publicist, on the phone with a dentist, “is there any drug you’re allergic to?”

She paused just a moment, long enough for every eye in the room to turn her way. Then she answered, in a voice like a fur coat snagged on a nail, “No, darling. There’s no drug I’m allergic to.”

I was entranced. She was precisely the age I am now, and she seemed impossibly glamorous and world-weary. She dismissed the memoir she had written the way you might dismiss a particularly noxious one-night stand. The only reason the publisher had wanted it, she said with a combination of pique and exasperation, was that she had once been The Girl in the Fur Rug whose heart was broken by Mick Jagger.

“It’s the Mick and Keith book, and that’s all. I told exactly no more, no less than was requested.” As she sat with a cigarette burning close to her pale fingers, she broke every rule of the publicity trail: She had loathed writing the book; there may have been truth in it, but it was not hers. “It was horrible,” she said. “Any normal person puts a lid on these things and never goes back.”

By the time I left, I was reeling, and more than a bit in love. Over the ensuing years I would interview dozens of people who’d written autobiographies – novelists and singers and astronauts – and I became fascinated with the self-imposed geometry of their lives, how they rounded off corners and ignored inconvenient angles. Which truths they told, and which they shielded their eyes from. And ours.

“Why do people write books anyway? To win. So your side of the story can win. Because they last forever. Longer than movies. Longer than music. Much, much longer than love.” That’s the main character in my new novel speaking. I say “new novel” as if it’s something I do all the time, but really it’s the first one, and possibly the last unless I get over the pain of a childbirth that took four years, and did not qualify for any hospital-grade medication.

The novel is called Based on a True Story and it’s the story of a faltering actress, Augusta Price, on the losing end of a fight with drugs, alcohol and the truth. When the story begins, she’s written a memoir, commercially successful but tethered only tenuously to reality. She discovers that her former lover is writing a book about her – one that will, presumably, expose the secrets that she’s been so desperate to hide. With the help of a failed young journalist, Augusta sets out to ruin the life of the man who will ruin hers. It’s a comedy, by the way. A comedy involving cats, fake vampires and tranquilizers (but not all at the same time.)

I’ve always been fascinated with liars, which is perhaps an occupational hazard since, as a journalist, I’m expected to tell the truth for a living. Take down what this person says, and report it verbatim. Do not guess at motive. Do not try to imagine what early-morning marital spat or unexpected diagnosis led to the grim face at the press conference. Do not try to worm yourself into their brains, or see through their eyes.

I think this explains the appeal of fiction for journalists. It’s like putting on the lightest muumuu after decades in a corset. Suddenly you’re invited to imagine the inner life, the inner lie. You’re expected to peek under the public veil, and interpret what you see, and make sense of what is hidden. Because it’s in the space between that the story lies.

There is an astonishing (and also slightly pants-wetting) moment when any journalist looks at the blank screen for the first time, fumbles for her notes, and realizes there aren’t any: “Wait, I’m supposed to make this stuff up?” Then she cries for a little bit, gives herself a slap, and sits back down. At this point, research must have been done. Novelists build their fiction on a foundation of fact: Zola climbed down into the mines, and Hemingway lowered himself into several highball glasses, all in the quest for authenticity. Me? I’d braved a lot of interviews over the years.

It’s amazing what patterns emerge once you’ve asked enough people to open up about themselves. The British really are more self-deprecating and naughty than their North American counterparts; film stars are usually “on,” and have disproportionately large heads, like golf balls on a tee; and memoirists are almost always squirmy, aware of the delicate striptease they’re performing in public. Too much? Not enough? Fact, or fantasy? Who from their past is going to step out of the shadows and scream, “lies!”

Toller Cranston’s irresistibly bonkers autobiography Zero Tollerance had been thoroughly lawyered when I went to interview him in 1997. Although it was filled with gossip and a viper’s sting, he declared “this is not a tell-all book, because if I told all I’d be arrested. There is nothing more boring than a person who tells everything.” He had a title picked out for the sequel: When Hell Freezes Over, Can I Bring My Skates?

Like Marianne Faithfull, he found the whole process excruciating. Every memoirist says this: It nearly killed me. So why do they do it? Sometimes for money, as Faithfull blithely admitted. Sometimes to make sense of a chaotic life. Sometimes for revenge: See Sir Vidia’s Shadow, Paul Theroux’s evisceration of his erstwhile friend, V.S. Naipaul. Why, I asked Theroux when I interviewed him, would anyone befriend a writer? “If you’ve got a writer for a friend, you’ve got a major headache,” he admitted. “And if you’re married to a writer – God almighty!”

Sometimes, as my fictional heroine Augusta argues, autobiography is a way to control the story that will live in people’s memories (for once, she is telling the truth). It can be a battleground. History is written by the victors; they write the memoirs, too.

Autobiography is the place where fact and fiction blend; the best ones are written by people who realize that a story, especially a life story, is only as compelling as the characters it contains. “This young man is no longer myself,” the Montreal poet John Glassco writes at the end of Memoirs of Montparnasse, his glorious reminiscence of life in 1920s Paris. “I hardly recognize him … he is less like someone I have been than a character in a novel I have read.” So said the man who told little fibs, and painted with brighter colours than he was given. Who cares? A stretched truth is still truth, just in more captivating form.

Elizabeth Renzetti is a columnist and feature writer at The Globe and Mail. Her novel, Based on a True Story, comes out June 14.

Roxane Gay: 'I was staring into very dark, nearly hopeless moments'

In some ways, it felt like I was cheating because my first novel, An Untamed State, was inspired by a short story I had written some years ago – Things I Know About Fairy Tales. In the short story, a woman is kidnapped and held for 13 days because her father is reluctant to pay a ransom for her release. The story ends when she and her husband are flying back to the United States. She is alone, in the cramped airplane bathroom, staring at a woman she doesn’t recognize in a small, dingy mirror.

The story had ended but I was haunted by the image of a woman feeling so lost and abandoned, feeling so terribly broken and unable to hold any sense of who she was or who she had been. There was more to be written, but at first, I was nervous. As a writer of short stories and essays, I did not think I had the ability to write a novel. There was something quite intimidating about the prospect of producing a 100,000 or so words that belonged together. I nearly talked myself out of the endeavour but I’m stubborn. I don’t like feeling defeated so I entered unto the breach.

I told myself I would write 100 very short stories and cram them together somehow. Something interesting happened as I began writing, though – I didn’t need to write 100 short stories. I simply needed to write one story and I needed to write that story as fiercely and honestly as I could. I needed to tell Mireille’s story. I needed to show how trauma often affects people far longer than we are wont to acknowledge in fiction. For a summer I wrote every day, all day. I became fully immersed in Mireille’s life – the beauty and brutality of it. There were times when it was hard to pull myself out of the world I created. There were times when I had no choice but to walk away to clear my head, to clear my heart because I was staring into very dark, nearly hopeless moments.

Fairy tales have always intrigued me. Though I didn’t have a real plan as I wrote, nor did I work with an outline, I was always thinking about fairy tales, how they are structured, and why they are so prominent in the cultural imagination – because they are, in ways great and small, stories about hope. In An Untamed State, Mireille is kidnapped and what she endures changes her; it changes everything about her life, her marriage, her motherhood. She must find a way to pull what remains of her life back together. She must find her way back to herself. The most challenging and the most exhilarating part of writing this novel was creating the story of a woman who finds the strength to survive an experience where a fairy tale is shattered; happy endings aren’t promised; but hope remains.

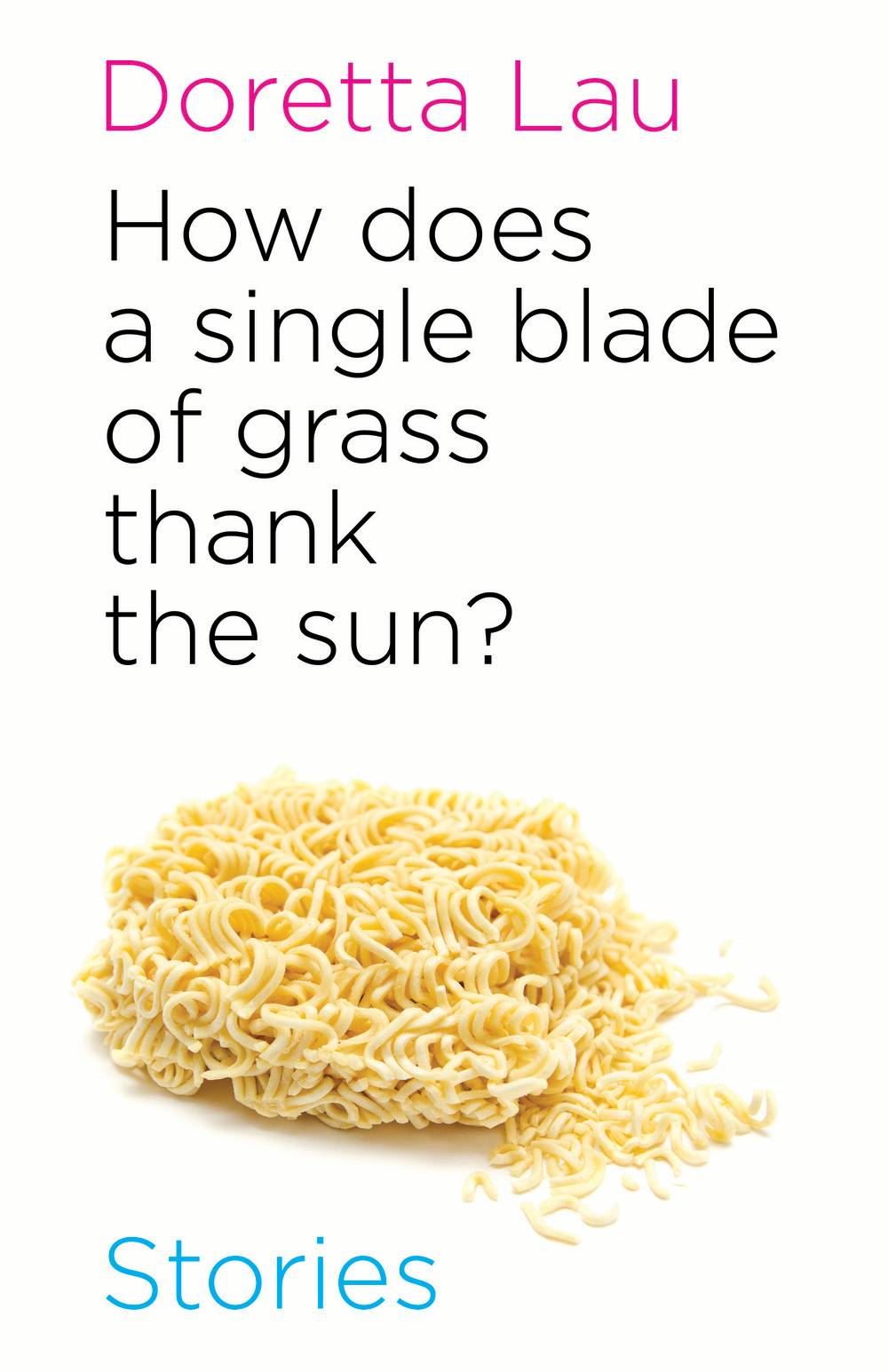

Doretta Lau: 'I have a problem with perfectionism'

Dorothy Parker said it best: “I hate writing, I love having written.” Perhaps this is why I decided to work on short stories rather than a novel; I wanted to experience the high of finishing a project over and over again, the having-done rather than the doing. I was a sprinter, not a marathoner. There were so many ideas to explore, myriad characters to love. How could I just stick to one?

Still, it took me more than 10 years to complete my collection – I have a problem with perfectionism. (I underwent hypnosis to deal with it.) I knew that I wanted to title my book after a line of Tang dynasty poetry about maternal love. In my mind the stories would salute the Asian Canadian writers who had written narratives about immigration, trauma and nation building. I had been afforded the freedom to write about anything I so desired because they had blazed a path for me. So I experimented with genre and form and wrote about neurotics, aspiring competitive eaters, former child stars, film students and ghosts.

During the last decade, I moved to three different countries. I earned an MFA in writing. I worked as a video store clerk, university admissions officer, research assistant, production editor, magazine editor and freelance journalist. I wrote in break rooms and hotel rooms. Every time I interviewed a writer, I asked about process. I read a lot of contemporary fiction because I fancied myself in dialogue with other writers when I wrote. That, I decided, was the entire point of writing – to be part of a community. Yet, whenever anyone asked me what I did, I rarely said I was a writer because I had not published a book and I was incapable of securing an agent.

To my surprise, I sold my collection before it was complete. I remember going to the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in Hong Kong to tell my friend Sam what had transpired – was it real? On the day I received my book contract, my publisher at Nightwood Editions, Silas White, asked me who might be willing to blurb my book. I named a few friends and sent off e-mail requests.

Last summer, I met the writer Gary Shteyngart at a dinner party. He entered my friend’s kitchen wearing a strange pair of glasses, which I thought were for driving. Soon, I discovered they were Google Glass – he was writing an essay for The New Yorker. Every time he looked something up he twitched like a malfunctioning robot. “Are you recording this?” I asked. “Where is Edward Snowden? Can you look up Octomom?” I had a lot of questions. Really, I was working up to the most important one: “Will you blurb my book?” He agreed to do it.

Now that my collection is out in the world – in bookstores, on nightstands, and floating in the electronic ether – I’d like to amend Parker’s statement to, “I hate writing, I love having published.”

Marissa Stapley: 'Don’t give up'

As I write this, my debut novel, Mating for Life, will be released in North America in just under one month. It’s been almost a year since the book sold to Simon & Schuster Canada and Atria Books in the U.S. The day the offers were to come in, my agent, Samantha Haywood, instructed me to stay by the phone. I kept thinking, “What if no one calls?” But the calls did come. On the surface, what happened to me looked like one of those publishing success stories, a rare but perfect moment when it all comes together for a first-time novelist.

In truth, my path to getting published has been anything but simple. In 2010, I wrote a novel that sold to Key Porter Books. In 2011, Key Porter declared bankruptcy, mere months before my novel was to be released. My agent tried to shop the novel to publishers again, but most had already seen it and declined the year before. I felt embarrassed when people asked me when the book I’d told them about would be in bookstores. Don’t give up, I told myself. I rewrote the novel into a Young Adult version, and still, the general consensus was, “Thanks, but no thanks.” Don’t give up. I wrote another novel. Getting published had become my sole ambition. It was all that mattered. It was my reason for writing.

When the second book didn’t get any offers, I couldn’t help it: I gave up. I stopped writing fiction and focused on my freelance writing career, which was going just fine. I was offered a job as the editor of a beauty magazine, and I took it. I missed using my imagination, I missed chasing my dream, but I told myself it was over. I told other people it was over. Then I stopped talking about it altogether.

Except I had a secret: late at night, after I got home from work, after the children were in bed, after my “real” writing was done – the kind that was not a pipe dream, the kind that paid the bills – I was writing short stories, stories about women who had grown up and were living the lives they thought they had always wanted, but were learning that happy endings didn’t always come easily. I wasn’t writing for anyone else, just for me. I certainly wasn’t writing these stories with the hope of getting them published. Sometimes the writing was painful; sometimes, it felt better than anything I had ever done. But I was so afraid to fail again that I kept it to myself. Finally, I worked up the courage to show the stories to my agent. I thought she would say it was time for our relationship to come to an end, but instead, she said, “These are good. I think you have a book here. Keep writing.” I did. (I had to. I couldn’t not write.) The characters started bumping into each other in new stories. Their lives connected, and eventually there was indeed a book: Mating for Life.

Now that I’m a soon-to-be-published author, I’m often asked for advice on getting published, and I still don’t know the right answer. There is talent involved, there is hard work involved, there is definitely luck and timing and serendipity involved, but there is also this: Don’t give up. Sometimes, in the darkest moments, only one thing can save you: writing it all down.