Even if the sky isn't pounding non-stop sparkling snow onto the winding highway in the dark, dark evening, Atlin, B.C., isn't the easiest place to reach.

Not that a difficult road has ever stopped Kate Harris from getting anywhere. Growing up in small-town Ontario, she was enchanted with Marco Polo's travels along the fabled ancient network of trade routes known as the Silk Road, linking Asia with the Middle East and Europe. After completing her undergraduate degree in biology, Harris finally set out on her own adventure across the Silk Road – on a bicycle with a friend, their panniers loaded down with gear, supplies and Moleskine notebooks as they slogged through often punishing conditions.

Harris's new book recounts those travels – first in western China, then their return in 2011 when they rode from Turkey to the Himalayas, over nearly 11 months.

So when I arrived in the northern B.C. village of Atlin, where Harris lives, to meet her, it seemed a little ridiculous to feel any sense of accomplishment about my slower-than-intended, white-knuckle drive south from Whitehorse in my Ford Focus rental. Still, she made me feel like a warrior for the achievement.

"I was going to go out looking for you," she said, in her duct-taped ski jacket. After reading her extraordinary debut book, I believed her. That's the kind of thing she would do. We sat down to dinner and our first of two interviews.

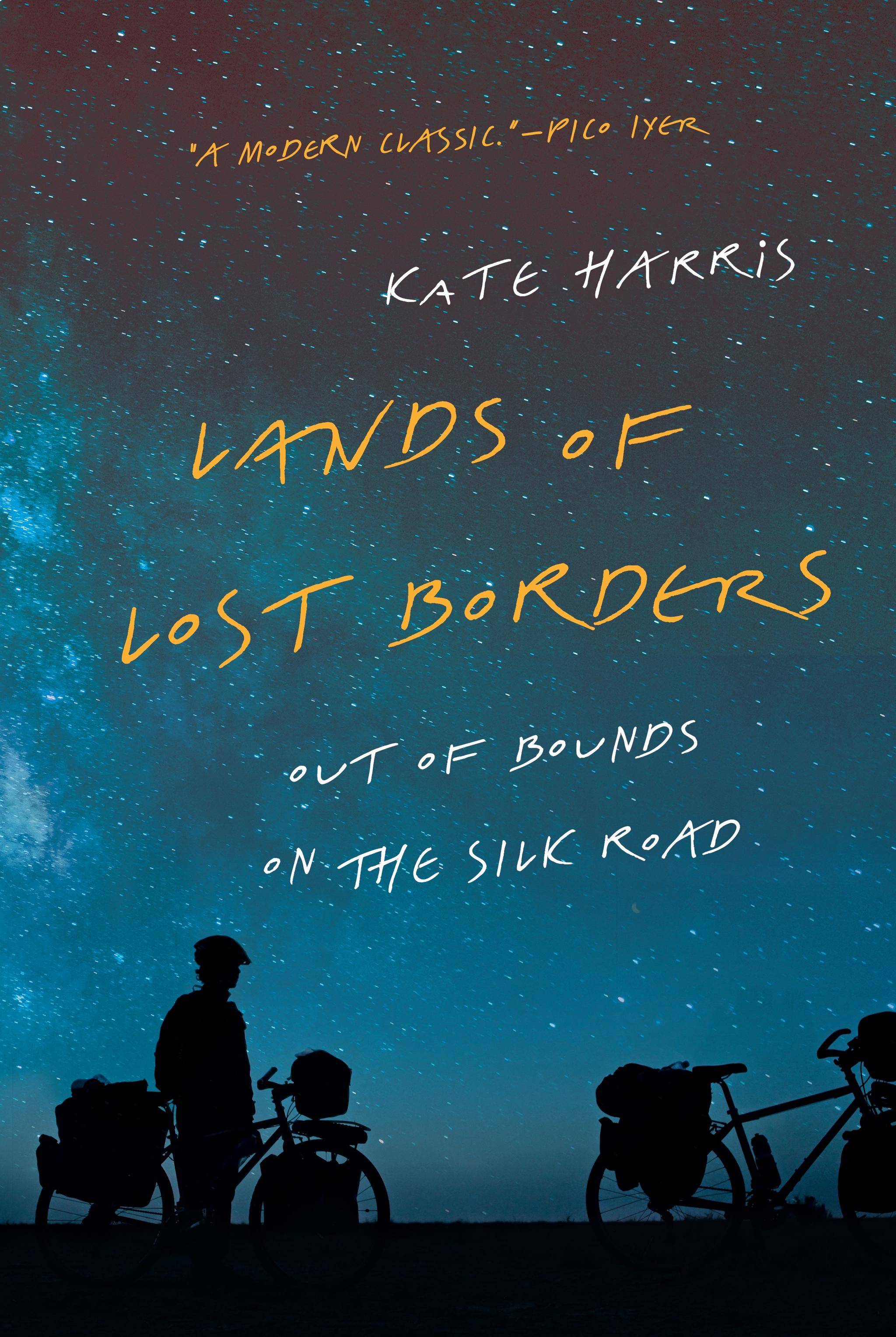

Lands of Lost Borders: Out of Bounds on the Silk Road is rich not only because of the adventures it recounts, but in the telling of them. It isn't so much a travelogue as it is a contemplation of what pushes us out the door and how we change out there in the world before we return to our own little corner of it.

This is not the type of book you want to motor through. Instead, it slows you down, so you can appreciate what you're experiencing – almost like a trip on a bicycle across an astonishing landscape. You find yourself wanting to linger, rereading passages built of sentences so beautiful they demand to be read out loud – even if no one else is in the room.

Lands of Lost Borders: Out of Bounds on the Silk Road contemplates what pushes us out the door and how we change out there in the world before we return to our own little corner of it.

"Every tree branch was fisted with buds and the air smelled of freshly chopped pine, earthy and warm, all those rays of sunshine released," Harris writes. "Every time I got on my bicycle after a long hiatus it was like riding back to myself, the only way there."

This book made me want to venture (!) to Atlin to meet Harris; it made me want to be a little like her, to go back and live my life differently – see different things but also see them differently. As she writes: "We're only here by fluke, and only for a little while, so why not run with life as far and wide as you can?"

Harris, 35, has always wanted to be an explorer. But for many years, her obsession was Mars. She built her academic and planned career path on becoming an astronaut, even attending a simulated Mars mission in Utah during her undergrad. There, she discovered an aversion to seeing the world through the Plexiglas of a space helmet. It should have been her first clue.

Harris had planned to become an astronaut, but ended up switching from studying science to the history of science.

While at Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship (an underachiever she is not), she switched from science – why spend your time in Oxford in a lab, she figured – to studying the history of science. This is where she found her groove, reading the journals of Charles Darwin and other explorers. When she returned to the lab, this time at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, she couldn't wait to get out. Instead of pursuing her PhD, she and her friend Mel Yule left for Turkey with their bikes.

They took videos, photos and mailed home their journals – snapping shots of each page for insurance – so they wouldn't have to lug them around. Years later, in her one-room cabin in Atlin, this reference material helped Harris get into the Silk Road headspace, looking out the window at endless trees from her desk, which is planted under a cathedral of built-in bookshelves; she calls it the skybrary.

The cabin is outside of town and off the grid, powered by solar energy and a backup generator. There's a woodstove, a propane oven and, a short walk away through the snow, an outhouse. There's no shower, no cell service; she drew a map in my notebook after our dinner so I could find the place again the next morning; a moose-hunting sign was one of the landmarks.

"It's nothing fancy," she said, not apologetically, ahead of my arrival.

Harris looks up at her ‘skybrary.’

So how does someone who has travelled all over the world choose Atlin, population approximately 400?

During her undergraduate years at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Harris could access summer travel grants. This was in part how she became a writer: She realized that words had the power to launch her anywhere.

In summer, 2004, she took part in a glaciology field program, skiing across the Juneau Icefield for six glorious weeks. The trip ended in Atlin. Harris fell in love with the place and never forgot. In 2012, she moved here with her partner, now wife, Kate Neville, who teaches at the University of Toronto, specializing in global environmental politics.

"I could pretty happily never go anywhere again. Atlin is situated in such a way that radiating out from this little community is wilderness … where nature is still just doing its thing and wildlife is doing its thing," Harris says.

Harris moved to the less-than-200-square-foot cabin in 2012 with her partner, now wife, Kate Neville.

"I can't see myself actually not travelling anywhere else," she clarifies. "But what interests me about Atlin is it's so easy to be dazzled when you go to a foreign land. Everything's dazzling; everything's new and odd and surprising. Every footstep's kind of like a new frontier. It's new territory. But there's a potential to be dazzled by a place where you live, day in, day out, that is so much deeper. … It's a much more profound acquaintance with a place than any sort of two-week flurry through a country on a bike can yield."

Harris compares the less-than-200-square-foot cabin to a haiku – five by seven by five (though she's not sure those are the exact dimensions). She wrote at the desk while Neville sat on the bench behind her working on her own book, an academic text about community responses to environmental land use, including fracking. They spent mornings writing with their black lab Daniel between them, afternoons out in nature.

"If you can't write a book here, you can't write a book anywhere," Harris says.

Over five years, Harris wrote and rewrote. For instruction, she read other writing that floored her – by Annie Dillard, Pico Iyer, Barry Lopez, Anne Michaels, Wallace Stevens, Virginia Woolf and others.

Their books and many others – including her mother's old copy of Marco Polo's Adventures in China – still line the cabin's ceiling-reaching shelves, the highest of which Harris can only reach by climbing onto her desk and standing on tiptoe (she plans to build a ladder).

What she finally produced is a book so good it drew both Iyer and Lopez out of blurb-retirement.

‘If you can’t write a book here, you can’t write a book anywhere,’ Harris says.

Iyer, who once wrote an anti-blurb essay, "Jacketeering," that Harris had been unaware of, nonetheless provided a glowing blurb, calling her book a modern classic. "Kate Harris packs more exuberant spirit, intrepid charm, wit, poetry and beauty into her every paragraph than most of us can manage in a lifetime," it begins.

"He wrote this gobsmacking blurb that made my life," Harris says, practically glowing next to the wood she earlier chopped. "Anything could happen with the book from here and it doesn't matter. If Pico Iyer thought it was a meaningful read, yes, that's enough. My life is made."

But what about Mars, I ask – is that still a dream?

"It's hard to convey just how evangelical I was about Mars as a kid. My whole mission in life was qualifying myself to potentially go there some day," she says.

But no more. "I think as the result of my travels I just have this deepening allegiance to the Earth. My loyalties are here," she continues. "It took a pretty naive version of me to prioritize space and Mars exploration above all else."

She thinks her next projects may be book-worthy: learning to fly (there are brick-like flight manuals among the poetry volumes) and learning to build. This summer there are plans to construct a second cabin on the property – for guests, especially writers. It will be lined with shelves, insulated with wall-to-wall books. What better way to keep a writer warm and inspired in a northern British Columbia forest?