Volunteers at federal prisons across the country are helping inmates foster a love of reading and the art of respectful conversation

In a nondescript lounge with cafeteria-style tables and a few vending machines, eight men have gathered to discuss a historical novel about a plucky housemaid fighting the plague in 17th-century England. The men quickly point to the parallels with the Ebola crisis and gradually tease out one of the book’s chief metaphors: Anger and betrayal spread through a quarantined village like a contagion.

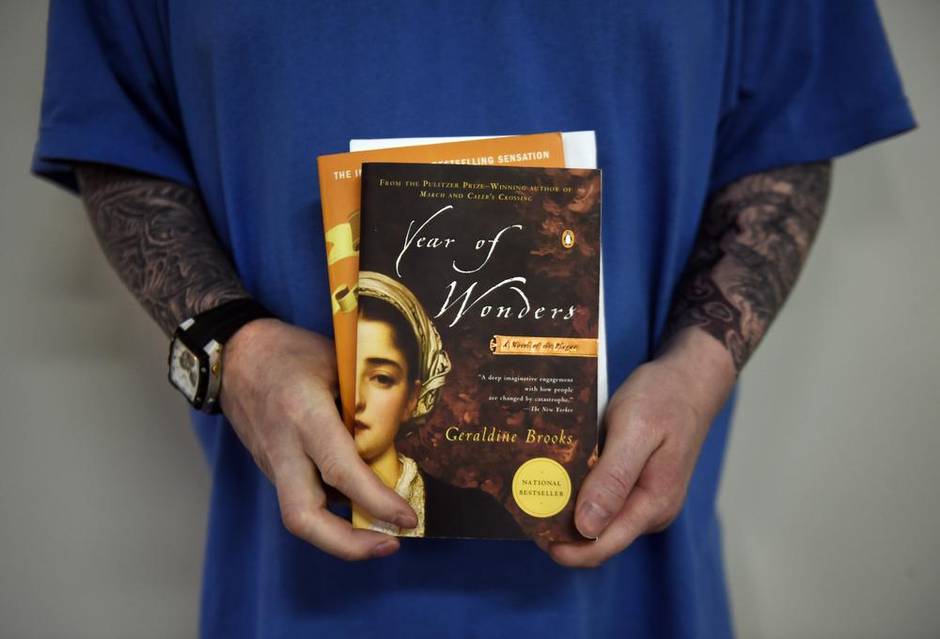

“The first pages got me. It shows you how much despair – and hope – there is,” one member remarks, describing a scene where the maid offers her stricken employer the thinnest slices of apple she can cut. After a thorough dissection of Year of Wonders, a 2001 bestseller by the American author Geraldine Brooks, they move on to lighter fare and a faster discussion of the popular Swedish novel The 100-Year-Old-Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared. There are two books on the evening’s agenda because the previous month the club members were in lockdown and couldn’t attend. They spent a week in their cells while guards searched the prison for contraband.

This is the book club at Warkworth Institution, a federal medium-security prison about two hours east of Toronto. Housing about 650 inmates including sex offenders, murderers and drug dealers, it’s the largest federal penitentiary in Canada. At some point, perhaps recently, perhaps years in the past, the men gathered in the visitors lounge have done horrible things.

But nobody here is talking about why they are here. They are talking about books and why they read them.

“Reading a book, sure, there is adventure, there is escapism, lifting yourself out of this reality, which isn’t always kind or welcoming,” says one inmate, a tall man who looks to be in his 30s. “[But] it’s in a purposeful and productive way. It’s better than drugs. It’s better than banging your head on the wall. It’s safe and builds something, knowledge, empathy.”

He makes it sound as though drugs and head-banging might be the real alternatives.

The book club at Warkworth is one of 17 in 14 federal prisons run by a Toronto organization called Book Clubs for Inmates. The group, a non-religious charity, sends volunteers into the institutions to lead monthly discussions and gets private donors to cover the cost of the books. The idea began in 2009 when executive director Carol Finlay, a retired Anglican priest and English teacher, began a club at the Collins Bay Institution, near Kingston.

“I went into Collins Bay. … I thought I would do prayers with the guys in segregation,” Finlay says, recalling how she discovered that nobody in prison needed any more religion. “I had to find something that was small ‘s’ spiritual: They are overwhelmed with volunteers evangelizing them. … I have always been interested in book clubs as a way of forming community. You may not like the book but you get together with people and discuss it.”

Armed only with a template from a prison book club in Britain, Finlay found herself in front of 20 tough-looking, monosyllabic male prisoners who, at the most literary end, had read a bit of pulp fiction. Others had not read any kind of book in years. Nonetheless they agreed to give the club a try. It quickly took off – although at one early meeting, Finlay and a volunteer had to separate two men who got into a fist fight over the book.

“They didn’t know how to listen respectfully,” Finlay says of the Collins Bay inmates. “We realized we had something to give them; what they call ‘pro-social skills.’”

Today, the clubs are operating across the country and now, with new additions in Fraser Valley, B.C., and Truro, N.S, in all the institutions for women. There’s also a recently formed francophone group in the women’s prison in Joliette, Que. The groups vary widely in their tastes and ambitions – at Fenbrook (now part of the Beaver Creek Institution in Ontario) the inmates have read The Odyssey – but Finlay figures whatever the inmates are reading the discussion is a more effective way of teaching social skills than mandatory anger management courses.

“All these guys are in prison because they thought only about themselves,” she says, noting most inmates grew up in dysfunctional families. “Because of how they were raised, it was everyone for himself. They don’t care if somebody’s life is ruined by the drugs they sell or if someone is shot … The book clubs teach them they belong to each other. It’s a community value they need.”

If the point of the project is teaching the art of respectful conversation, you could not ask for a better example than the book club at Warkworth where the inmates discuss whether Year of Wonders is a feminist novel and dispute the idea that the 100-year-old man should necessarily be compared to Forrest Gump. The conversation is often indistinguishable from what you might hear at a book club gathering over glasses of white wine in a suburban home. The inmates provide the tea and cookies.

“I belong to two other book clubs and I often feel the conversation at the prison is just as stimulating,” says Erin, one of three volunteers who goes into Warkworth every month to lead the group discussion. The only difference, laughs Judy, another volunteer, is that this club always discusses the book.

It’s the volunteers’ job to keep the discussion on track; they come prepared with various themes they want to raise if the inmates don’t cover them. On the instruction of the Correctional Service of Canada, they don’t share their last names with the club, while Finlay provides them with guidelines about respectful conversation that are to be read at the start of each meeting. At Warkworth, the volunteers don’t see the need and have dropped the practice. Their club takes place without any guards in the room but under the watchful eye of Warkworth librarian Bob Fasching; he has a silent alarm on his belt, which, the volunteers say, he once pressed inadvertently – to the great amusement of the inmates when guards burst in on their literary discussion.

The inmates vote on what titles to read from a list compiled by the volunteers based on both their own reading and Finlay’s suggestions from other clubs. The volunteers try to balance fiction and non-fiction and find the inmates are looking for substantial if not overly lengthy reads. Crime fiction is not popular; novels about unhappy families are. Warkworth has had animated discussions about Jeannette Walls’s poverty memoir The Glass Castle and Lawrence Hill’s slavery novel The Book of Negroes. This year their reading list includes a memoir by baseball pitcher R.A. Dickey (Wherever I Wind Up); a biography of Muhammad Ali (Ali) and a novel told from the perspective of an autistic boy (The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time.)

“I came here from another prison where we used to hoard magazines,” says one inmate. “I had to go through several grievances to buy a dictionary. That’s how hard it was to get any sort of book. You could get a basic cowboy novel, stuff like that. Here, it’s books galore.”

The books have to be purchased new and shipped directly to the prison; donated titles would create security problems, Finlay explains, because books are a perfect place to hide contraband. This makes the book clubs, which operate 12 months a year since the inmates don’t take vacations, an expensive proposition. Finlay tries to secure a single sponsor for each club at the cost of $5,000 a year, seeking out philanthropists who grasp the concept of rehabilitation.

Erin, who never asks what crimes the book club members have committed, says she very occasionally meets someone on the outside who doesn’t get it.

“I have people who say to me these inmates are not deserving of a book,” she said, “People have to realize some day these inmates will get out and will be sitting beside you on a bus or chatting to your kid on the street. Everybody deserves a chance to get themselves back together.”

The inmates themselves say they value the social aspect of books – the man who fought for a dictionary gets his wife to read the same books so that they have a common experience to discuss – but also they see books as a way of gaining access to themselves.

“I usually read non-fiction. The books we read in book club I wouldn’t necessarily pick up,” one older prisoner says. “But I am really glad I read them, and each and every one I have more insight into myself.”

“Feelings aren’t really popular around here,” explains the inmate who prefers reading over drugs. “[Reading provides] a kind of freedom that we can’t access at the point in our lives where we are and really taps into a bunch of emotions. Groups like this, little pockets of honesty, expression, are at a premium.”

Others say they read books simply to stay sane inside.

“This is heaven for me,” one enthusiastic newcomer to the group says. “It’s a place where I feel like a human being.”