The last time we went to the Gelmans for Christmas there were still forests north of Steeles Avenue. Philip and Bun lived in an old house at the bottom of a hill with a pasture on one side and a wall of pine behind it that concealed both a small lake and a ghost town.

Their house was hidden below the road. You went down a long driveway and did a hairpin turn to park under an awning. The entrance to the house was through the basement and the house loomed over the doorway like something on a hill. They'd flick the lights on when they heard our car and come thundering down the stairs. We only saw them once a year, which was the optimal interval to visit the Gelmans, a strange family comprising a Jewish father, a Catholic mother and adopted fraternal twins, George and Jeanette. I'd known twins before – they cropped up in my mother's line like mushrooms – but a Jew married to a Catholic? Never.

It was 1978 and the Toronto Maple Leafs were second in the Adams Division. Philip, being a Mancunian football enthusiast, respected that I was passionate about the Leafs but he knew nothing about hockey. He called checking "tackling" and claimed there was no holier experience in all of sport than a nil-nil at full time. Over roast beef, he clinked his fork against the crystal and called on someone to entertain the table. This meant concerts performed by his freakishly intelligent twins, or, if any of the five of us were called on, imitations, fun facts or singing. Yearly, George, when named, left the room and returned with either a French horn or an accordion. Jeanette played piano.

It was my talent to stand and produce the sound of an angry elephant, but this year, when Philip called my name, he forbade me to make animal sounds. "You must have started your bar mitzvah lessons by now. Give us a taste."

Bun put her hand on his arm. "Don't make him chant Torah on Christmas Eve," she said tenderly.

For as long as I could remember, which at the age of 12 was almost my whole life, our dinners with the Gelmans ended with the adults groaning in chairs with snifters in their hands and the children banished to the basement where the games were. The twins were 14 but so different they might have been years apart. George had a soft, boyish face atop huge shoulders, and Jeanette was delicate and poised. Their personalities were reversals of their bodies, though. George was shy and gentlemanly; Jeanette direct. I felt something for Jeanette that was almost like fear.

My sisters endured George's trains while his sister ignored us all, reading a heavy book in a chair. I stood near the fireplace and warmed my hands. Through a window, the light from upstairs lay in a yellow pool on the gravel. I heard a burst of rude laughter and then footsteps. Someone put on an LP.

"Can you see without your glasses?" Jeanette asked me.

"Not so good. Shapes and things, but I can't read."

She took my glasses from my face and held the spine of her book up to me. "What's that say?"

"War and Peace?"

She handed back the glasses. "I have 30/30 vision," she said. "That means I can see parts of the spectrum other people can't."

"What's that look like?"

"Can you think of a colour you've never seen?"

I thought about it. "I guess not."

"That's what it looks like," she said.

Bass tones thrummed from the ceiling. Our conversation stalled because it was my turn to come up with something interesting, but I had nothing. Jeanette swivelled back and forth on her heel.

"You want to see my mother's comic books?" she asked. "She has really old ones. Her dad gave them to her after he died. She keeps them in her office." She led me to a door under the stairs that opened on a cramped room. A pull-chain lit a naked bulb. I saw my sisters' little eyes following George's trains around the track. "Come on," she called to me. "You can sit in her chair."

The desk and chair faced the bottom of the stairs and the area behind it was big enough for one normal-sized person to stand up. A typewriter sat perfectly centred on the desk, a bean-bag ashtray beside it full of ash. The tiny room smelled like stale smoke. Jeanette pulled out a white box with a tight lid. "Is it okay that we're in here?" I whispered.

"They're sauced to their teeth," she said. "Hold this." She passed me the lid. In the box, standing up, were about 50 comic books in plastic bags. She pulled one out at random. Batman and Robin trapped in a cage and the Riddler laughing maniacally. "He's probably mentally ill," she said. "Do you know what mentally ill is?"

"Yeah, you. What does your mother do down here?"

"She writes stories."

"About what?"

"I don't know." She opened the desk drawer. A neatly squared stack of paper lay centred in it. She took the top page off and turned it over. Black type ran from margin to margin. " 'Elvira's cheeks were flushed and hot,' " she read. "'Her tummy did a flip and she realized she wanted Marcel's big hands all over her.' " She put the page back onto the pile but pulled her hand away quickly. A dash of blood appeared on her fingertip.

"Your mother is a piano teacher," I said.

"People aren't just one thing, Nathan." She peeled the plastic tape off the back of the comic bag, leaving a translucent red smear on it. "She says these are worth, like, more'n a hundred dollars each. I happen to know this one is worth a thousand. Do you want to smell it?" She took the comic out of its bag and spread the pages. "Smell it." I leaned down and put my nose to the paper. It smelled like my father's toolshed. I liked it. I felt Jeanette's face in my hair and heard her breathing. In my ear, she said, "Because you're Jewish, you don't have to kiss under the mistletoe."

I took my nose out of the comic book.

"Mistletoe," she repeated, pointing up. A sprig of it was tacked to the underside of the stairs. "But you can if you want to." She smiled at me and then I heard our names being called.

I burst out of the room and instantly the air felt cold on my skin. "Here!" I shouted. George had already taken my sisters upstairs.

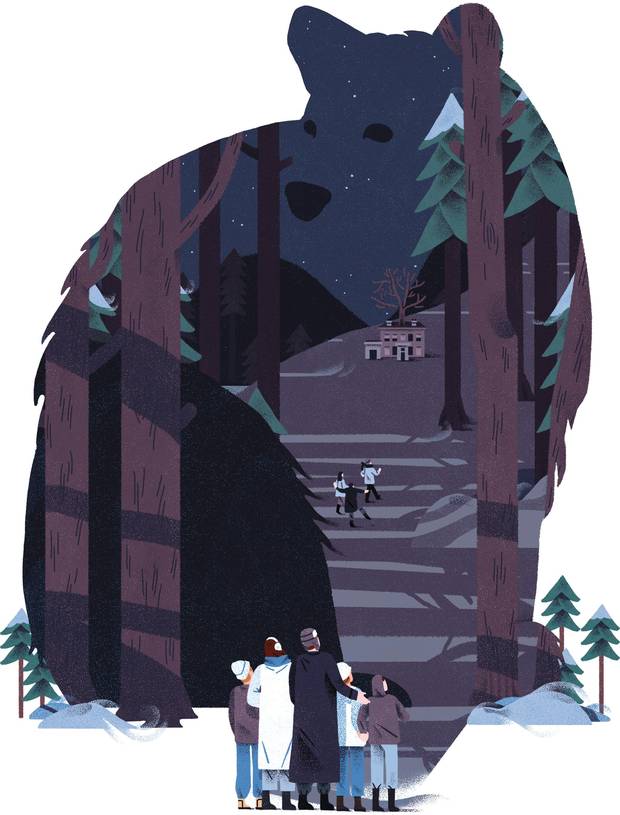

It was time for the Christmas hike. There would be a flask and my father would make jokes about something called "cockles." I'd always liked forests and walked in them alone and unafraid from a young age. I'd been immune to Grimms' fables and didn't fear the woods except the ones behind the Gelmans' house because of the ghost town. Bun, being from the nearby town of Maple, had told us that the collection of buildings used to be part of a place once called German Mills.

Philip and my father passed the flask back and forth as my mother and sisters walked ahead with Bun, who held the flashlight. It made a bright, granular cone on the hardpack.

The twins walked with me. "I hope you didn't disturb Mummy's papers," George said.

"Mummy's papers are already disturbed," Jeanette replied. "Nathan was quite taken with them, weren't you, Nathan?"

I ignored her and asked George if he'd read any of it. "I don't snoop," was his answer.

Up ahead, my father and Philip sang Popeye the Sailor Man, the version where he goes swimming with bare-naked women. Every year I forgot how far the walk was. When I turned around, I saw the forest had already closed in behind us. Philip was a tripper and carried a compass on his keychain so he'd never get lost, but I didn't feel safe walking in the dark with him, or the other drunk adults.

"TOOT TOOOOT!" cried my father, and sat down in the snow. "Oh, look." He pointed at a snow-covered shack with a tree growing through its roof.

My mother pulled him out of the snow and we gathered together in a tighter group as we walked down what might have once been a main street. Beyond the tree-burst shack, a loose grouping of decaying buildings appeared, set at odd angles against each other.

Bun wrinkled her nose. "What is that?"

We all sniffed the air. A slight but detectable scent of rot. It got stronger the deeper we went. My mother wanted to turn back, but Bun put her arm around her and said there were rarely dead bodies in the woods. We all laughed, but we still sharpened our senses against what felt like an intrusion.

"I think Henry farted," Philip said. His laugh rattled off the flat surfaces. He gave my father a playful sock in the arm.

"It's much worse than that," said my mother, and everyone laughed. "It smells like an animal den!"

The moment she said it, I heard a growl.

"Nobody move," Philip said. The sound came from a shed with a missing door and a collapsed roof. "It's an animal."

"Let's go," said my mother.

Philip took the flashlight from his wife and pointed it at the shed. A glint of steel flared and behind it, a white eye. He dropped the flashlight.

Bun said, "God, Phil," and snatched it out of the snow. She had to rattle it back to life. "That's a cage in there!"

The adults crept toward the shed. Behind them, the children watched in complete stillness, scared out of our wits. "Dad!" I called in a low rasp. "Mum! Don't go in there!" But they weren't listening to us. We heard the rumble of the animal's fear, followed by a moan that admitted all was lost. Philip turned and gestured for us to come closer, quietly.

We crept up and they made space for us. It was a bear, a small brown bear, Philip told us. It kept snarling, but in a tone of surrender., and it tried to make itself tiny. "Someone's left it here for animal control to pick up."

"They'll put it down!" cried Bun. "Poor little dipper."

"Let it go," George said, and immediately my sisters, whose only knowledge of bears was stuffed animals, chimed in to release it too.

My father picked up a fallen branch and held it in front of him. "Everyone move back," he said.

My mother plucked at his coat. "Henry, don't."

"Georgie is right, hon." He waved the others away from the entrance to the shed. "It's Christmas Eve for heck's sake. Poor thing."

Against everyone's protests, my father went into the shed. Bun's flashlight beam made a circle against his back that spread like an eye widening. I suddenly imagined his face gashed with red stripes and the howling of animals. Someone tugged at my glove. It was Jeanette. She pulled it off and tucked it into her pocket and I felt her bare hand slide into mine. No one was looking at us. I hid my shivering in the cold.

My father dragged the cage from the shed and the flashlight's beam followed the animal's form into the open. Bits of its hair lay like iron filings in the snow. It was smaller than its growl. I felt awful for it.

"Its paw has been in a trap," Philip said. "Look at it."

We looked at the mangled paw. "Put it back, Henry," my mother said. "Someone means to pick it up."

The children wouldn't have it, though. It was too helpless. My sisters were already crying. "Let her go," said Jeanette. Everyone turned to look at us. I tried to pull my hand away, but she held it tight. "She'll hibernate and her foot will be better in the springtime."

The adults stood around silently communicating with each other. Then my father turned the cage toward the end of the dead town and pulled the steel pin from its gate.

"Get back, you idiot," my mother called to him. He took a few steps away, holding his stick in front of him. We stood as quietly as we could. The bear wouldn't accept its freedom at first, but after another minute, it tested the opening and emerged, smelling the air. My father clapped his hands and it broke into an awkward run toward the cover of the evergreens.

My sisters and father were fast asleep by the time my mother made the right-hand turn onto Yonge Street. I took my glasses off and tucked them into the pouch in the back of her seat, and through the windshield the traffic burst into blossoms of red and white. I wondered if the bear was going to find its family or if it was going to die alone in the woods, and I couldn't decide if my father had been a hero or a fool. It was a question I continued to have throughout my adolescence and into adulthood. I know the answer now, but it no longer matters.

In memory of David and Philomena Treissman.

Michael Redhill's novels include Bellevue Square, winner of this year's Scotiabank Giller Prize. Follow him on Twitter.