Author Elamin Abdelmahmoud.Kyla Zanardi/Handout

When I was young I thought “Africa” was a sad place. I had travelled from Canada to my home country of Sudan to visit family only a handful of times. And in my child’s eye, I remembered Sudan to be a place of dust and wasteland, which I thought – from listening to the world around me – was indicative of all of Africa, a place that was suffering and in need of help. Compounding these ideas were the stories about Black people that I learned in school history books. Oh, poor Black people, I thought, look at what they’ve had to endure.

Looking back, it hurts to see how narrow my thinking was. I was laser-focused on the sadness I thought I saw around me, completely oblivious to the joy that radiated from the people and places I had visited. It wasn’t until I started doing my own research, reading books by Black authors telling their own stories, such as Leila Aboulela and Nnedi Okorafor, that my eyes opened to the realities of what Blackness could be, and I realized that ideas I had of Sudan, Africa as a whole, and by consequence, Black people themselves, were nothing short of detrimental.

Black trauma and tragedy are prevalent in our television shows, books and movies. We are saturated in stories of violence on the news and social media, with few tales of positivity, even though they certainly exist. This is especially true when it comes to media that’s promoted during Black History Month. We’ve all seen it. The book lists that are hyper-focused on Canada’s history of slavery and, especially post-George Floyd, works about racism. And when we’re done consuming them, where do our ideas of Black people go? Do they stay within those stories? Or do they end up somewhere different?

These painful stories are so important to our everyday understanding of the Black experience. But many of the resources that fixate on trauma cater mostly to the white gaze and ignore the full picture of what it means to actually be Black. Black History Month then presents an opportunity – though it is rarely used – for us to take an equal look at the joy of being Black in our stories of falling in love, connecting with family, finding pleasure and purpose within ourselves and our communities.

Three Canadian writers are bringing such stories to the forefront, each with their own country’s culture informing their work: Trinidad, Nigeria and Sudan. Their stories are told through their own lens. Liselle Sambury’s deep personal interest in her family and the genre of fantasy, Jane Igharo’s passion for Nollywood movies and romance, and Elamin Abdelmahmoud’s intrigue with defining his identity. These books are great representations of Black joy, in how each author sees it themselves. They’re varied, nuanced and wonderful.

Elamin Abdelmahmoud (Son of Elsewhere: A Memoir in Pieces)

It’s a special moment when you read a book that not only speaks to your interests, but also your identities, or even better, the intersections of your reality. Abdelmahmoud, a BuzzFeed writer and CBC podcast host, offers exactly this in his upcoming memoir, Son of Elsewhere (out May, 2022), which cuts between vignettes of Sudan’s colonial history, Abdelmahmoud’s childhood in Sudan and his memories growing up in Kingston, Ont. For Sudanese people, Abdelmahmoud tackles what it means to be from Sudan and “Black,” and the messiness of their colonized Arab identities.

He talks about his yearning for a “Blackness” that he had never known: “Am I still hesitant to own that I am Black – still protective of aspirational proximity to whiteness?” asks Abdelmahmoud in his book, “The short answer is ‘maybe.’ The long answer is that I am still discovering the ways I learned to hate myself.”

Handout

Abdelmahmoud’s “memoir in pieces” is just that: stories from his life put together in discovery and questioning. In particular, he explores how his interests in wrestling and listening to rock music – two distinctly Kingstonian pastimes, first taken up with an intention of assimilating to white culture – became part of his search for Blackness.

As Abdelmahmoud understood and redefined his relationship to his race, it enriched his life in immeasurable ways. “It gave me access to a profound archive of struggle, grace, friction and joy,” he said in an interview. “I’m still spending time getting to know that archive. So right now, I just have a lot of gratitude.”

As an adult and father today, he is able to bring more context to stories and images from his past. The joy and tenderness he radiates when he describes his family in Sudan and the relationships he’s cultivated in Canada to places, people and things really ground the memoir. “Black joy is being held in community by people you know, people you love, people who thrive on seeing you thrive. It’s something to cultivate, something to carefully plant and water and tend to. It takes time and energy and intention to care for your people and let them care for you,” Abdelmahmoud tells me.

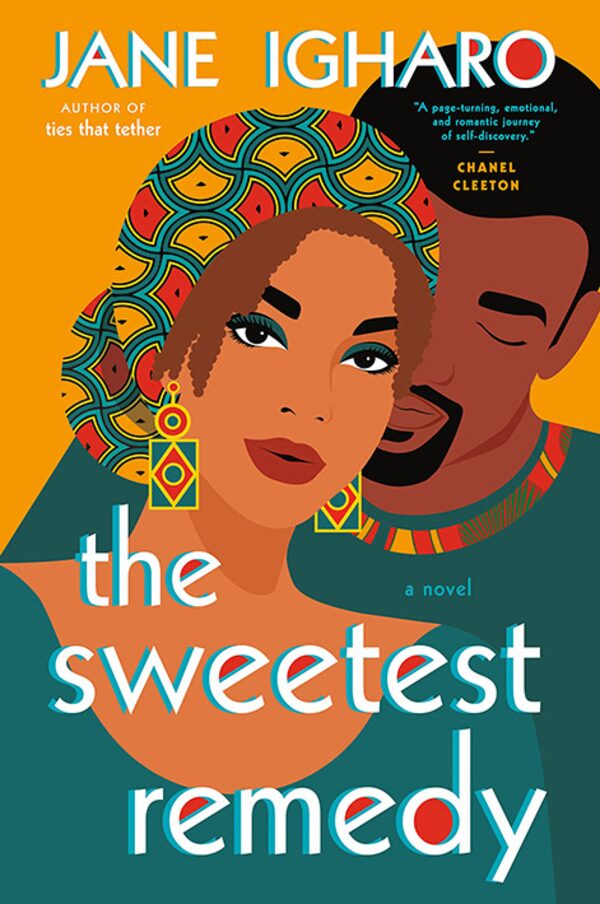

Jane Igharo (The Sweetest Remedy)

Author Jane Igharo.Borada Photography/Handout

“I study love, and explore all the things that it is – and all the things that it’s not,” Jane Igharo says as we chat about her book, The Sweetest Remedy. The novel, which introduces us to the larger-than-life Jolade family in Nigeria, is loosely based on her favourite Nollywood movie, Chief Daddy. Igahro offers a fresh look at romance with Hannah, a biracial American who barely knew her rich Nigerian father, of the Jolades, and smooth-talking, sensitive Lawrence, who soothes her worries and quickens her heart.

Handout

“For this book it was important to show that aspect of Black people and Nigerians – that they’re so multi-layered in their talent, ideology, in their fear and vulnerabilities and in how they love…all the characters have their issues going on, but they love each other.”

A delight to listen to, the audiobook version has the narrator switching between Nigerian Pidgin, Brooklyn and London accents in ways that seem natural and enriching to the story. The complicated relationship between Hannah and her half-siblings adds a different layer to the romance novel. In her book, Igharo strives to showcase how people experience Black joy in simple ways, including the way they interact with each other. “Black joy is Black people experiencing joy and happiness in the little everyday things, in their relationships with each other.”

Liselle Sambury (Blood Like Magic)

Author Liselle Sambury.Stuart W/Handout

Born and raised in Canada, Liselle Sambury didn’t know much about her Trinidadian ancestors. When she began writing her debut novel, Blood Like Magic, she started asking questions, and eventually traced her ancestry back to enslavement.

“How would it feel to be someone living in the near future to try to connect with someone whose past seems so far away from them?” she asked herself after the revelation of her family’s history.

Sambury brought this historical perspective to Blood Like Magic, a blend of the old, the new and the imagined in what some would call an iteration of Afrofuturism. She writes about a young witch, Voya Thomas, who needs to kill her one true love in order to save her family’s magic. Voya’s ancestors passed along traditional Trinidadian practices informing the future in which the Thomas family lives in 2040′s Toronto.

Sambury flawlessly weaves in Trinidadian culture without explaining it, so the onus is on the reader – whether they’re familiar with it or not – to teach themselves. In that way, the book feels more like a fantasy, sci-fi story that just so happens to have a Trinandian main character.

Handout

Blood Like Magic opens up the discussion on what Black joy is to individual Black people, as shown in the variety of characters who are mixed-race and identify as LGBTQ. They are written with intentional nuance in their identities, personalities and the ways they enjoy life, with interests ranging from cooking, hair care and sewing. “Each character is free to be themselves and express their joy in their own way,” Sambury says.

When I ask her more about what Black joy means to her, she tells me, “It’s the ability to be yourself however you are as a Black person, and not have that taken away or diminished by struggles that exist in being Black.”

Sambury sees the lack of balance between trauma and joy during Black History Month – or what she dubs White Guilt Month – and says that it has trickled down into her experience as an author. “When I was first joining the writing community, there was very much this feeling of ‘Nobody wants your Black fantasy book,’ ” she says. “If you’re a Black author and want to get published – it was contemporary, it was trauma, it was pain.” Sambury says she was lucky to have a great agent and land a book deal without much push back but acknowledges that there is still a ways to go for other Black authors and the publishing industry as a whole.

She offers this advice to Black writers “Please write what you want, what you’re most passionate about and what you want readers to read. I know sometimes it’s hard to divorce yourself from what will sell, but we need people to do it.”

While we are seeing more wonderful stories by Black Canadian authors that balance trauma and joy, I think it’s safe to say that there is still a tremendous lack of nuance and context to the Black experience that needs to be confronted in Canada.

These stories of joy exist, even if they aren’t published yet.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.