Genre writing is dense with tropes. They make the genus familiar and cohesive. They help set it apart from others, even though genres, like the tropes that help construct them, twist and bend and intersect. Heist writing is a genre of its own, but it crosses boundaries to connect with others. You have sci-fi heists, noir heists, romantic heists, mob heists, fantasy heists. Whatever sort you can possibly imagine. There’s always something to steal. And there’s always someone, or some crew, to steal it.

The brilliance of a good heist book – or film, television series, or game – is partly dependent on the characters (what endeavour isn’t?). But the heart of the thing is in the machinations of the steal and the relationships that shape the job before, during and, most importantly, after. If a mystery novel tends to ask “Who did it?”, a heist novel asks “How did they do it?”, followed closely by “What now?” After all, by the dictates of the genre, the thief or thieves are up against long odds, mismatched but interdependent characters, betrayals, distractions, unexpected twists, a distracting thirst for revenge and, of course, the lure of … one … last … job. And then they’re stuck with the loot. And each other.

In Six of Crows (Square Fish, 2015), Leigh Bardugo draws on familiar tropes built around an intricate fantasy realm – part of her Grishaverse – to tell the story of Kaz Brekker and his crew of young crooks who set out to capture a prisoner being held by a rival state in an impenetrable fortress. The man who has been taken holds the secret to a destructive discovery that not only alters the balance of power in their world, but threatens to utterly upend the realm and sow chaos.

Marketed as a young-adult novel and told from the alternating perspective of several characters, the book is brilliantly plotted, exquisitely written, properly paced and deeply compelling. The dialogue reads true. The characters and world are developed in tandem with the right mix of backstory, exposition and bits you’re left to figure out for yourself. Themes of class, prejudice, and justice add heft to the page-turning drive of the plot, and a subtle noir edge brings the whole thing together. In that morally ambiguous spirit, we find Kaz at the outset of the book extricating himself and his crew from a trap set by a rival gang. “You’ll get what’s coming to you someday, Brekker,” says Geels, as his plan fall to entrap his opponent falls apart. “ ‘I will,’ said Kaz, ‘if there’s any justice in the world. And we all know how likely that is.’ ”

Justice is a common theme in heist stories. It acts as a moral force, an argument, implicit or explicit, that the ends justify the means, which they do sometimes. Here’s the deal. These folks are going to steal this thing, but the victim of the crime had it coming. There’s a greater good in the mix. In Portrait of a Thief (Tiny Reparations Books, 2022), Grace D. Li relies on this force to animate her story of a series of amateur thieves, college kids who take on a job they have no business trying – to steal precious pieces of Chinese art held by Western museums around the world and turn them over to a collector in China. The score promises a big payday, but the crew is also chasing justice for their homeland as they reflect upon and seek to right, in some small way, the looting and burning by the British and French of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing during the Second Opium War.

Portrait of a Thief follows the familiar heist tropes itself. Assembling the crew. An impossible score. Twists and turns and failures (or are they?). The premise of the book is excellent, but the characters are underdeveloped while their connections to one another often feel tacked on. The heist bits are thin and amateurish, but that may be by design. The crew is, after all, amateurish. The recurring exploration of familial pressure, the drive to succeed and striving for justice – a form of vigilante reparation – in the face of past and present colonialism adds welcome depth to the story, though. As the crew’s leader, Will, thinks on what he’s about to do, he reflects that he “had always known history was told by the conquerors.” The book collapses history into the plot, and thus into the heist, and is all the better for it. Indeed, that bit probably saves the book.

Lest anyone think the best heist stories are fictional, enter The Feather Thief (Penguin Random House, 2018) by Kirk Wallace Johnson. You might expect the tale of a heist of rare birds from a British museum is the stuff novels, but it happened. You might think it would be dull. Birds? Who cares? But it’s rivetting. The story is wild, not unlike the birds themselves, and even more so when you consider the fact the avians were stolen for their feathers, which are coveted by fly tiers, many of whom don’t even fish.

The author himself puts it best as he reflects on being pulled into the mystery – and its resolution. Near the beginning of the book, Johnson writes, “Little did I know, my pursuit of justice would mean journeying deep into the feather underground, a world of fanatical fly-tiers and plume peddlers, cokeheads and big game hunters, ex-detectives and shady dentists.” I was hooked by the end of that sentence. But Johnson brings the point home, a point explored throughout the book, concluding, “From the lies and threats, rumours and half-truths, revelations and frustrations, I came to understand something about the devilish relationship between man and nature and his unrelenting desire to lay claim to its beauty, whatever the cost.” The book is a classic heist tale and assessment of theft, greed and the desire to possess what isn’t yours if there ever was one.

Can’t get enough of heists? Here’s more:

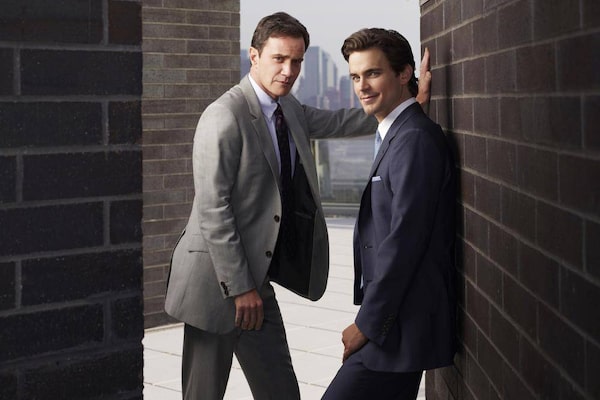

FBI agent Peter Burke (Tim DeKay) and Neal Caffrey (Matt Bomber) in White Collar. The show tells the story of a con man released from prison into the custody of a white-collar crime division FBI agent.Bravo

Television

When it comes to heist films, I like to pay attention. Phone down. Eyes up. For whatever reason, when it comes to their television counterparts, I like to have them on as background. But not all backgrounds are created the same. White Collar tells the story of a con man released from prison into the custody of a white-collar crime division FBI agent. Each episode is a mini-con or heist of its own wrapped inside a broader game of cat and mouse. It’s not art but it’s a tropey good time.

In Thief, James Caan delivers a rare understated performance as the professional thief Frank, whose successful Chicago businesses are a front for his real vocation of stealing things.United Artists

Film

There are dozens upon dozens of top-shelf heist films. Too many to list here. The internet is full of lists of must-sees. But one title that ought to be on each list is Michael Mann’s feature debut, Thief (1981). A neo-noir starring James Caan, Tuesday Weld and Jim Belushi, and featuring Willie Nelson, the film traces the late career of a safecracker who takes on one last job. It’s heavy with moral ambiguity, pathos, crackling dialogue and, of course, an anti-hero or two. It’s near perfect.

Video game Payday 2 ranks among the best heist games as players assemble a crew to commit heists.Handout

Video Gaming

Heists are a big part of video games, appearing frequently as side quests or main missions. There are a few games that are fundamentally about heists, of which Payday 2 is probably the best. The game is a co-op undertaking in which you assemble a crew and, you guessed it, commit heists. The game is several years old, but it holds up. If you prefer something newer, Payday 3 is due out in 2023 on console and PC.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.