Crad Kilodney sold his self-published short stories and novels on street corners, in blistering summer heat or frigid snowstorms.1996-2004 AccuSoft Co., All righ/Handout

If you spent any time around the literary community in downtown Toronto between 1976 and 1996, you eventually ran into Crad Kilodney: the cranky, pipe-smoking, helmet-haired writer and sworn enemy of the Canadian literary establishment who wore giant hand-drawn signs around his neck (“Shabby No-Name Writer,” “Literature for Mindless Blobs”) and sold his self-published short stories and novels – Lightning Struck My Dick, Excrement, Blood-Sucking Monkeys From North Tonawanda, to list a few of his better sellers – on street corners, in blistering summer heat or frigid snowstorms. You might even own one of his books, for which you probably paid $2 to $10, and which (this is a tip) you should hang on to.

Anthony Stechyson, on the other hand, is a 35-year-old millennial, and had never heard of Kilodney until April 14, 2014, when he read an obituary on the Literary Review of Canada’s website. “Cult Writer Crad Kilodney Dies” the headline declared, next to a photograph of the author standing on the street wearing a sandwich board advertising Putrid Scum and “looking very angry,” Stechyson recalls. A filmmaker and student of countercultures, Stechyson had never heard of him. Then again, obscure outliers who swim outside the mainstream are not a species we fuss about these days.

A few weeks later in a second-hand bookshop, Stechyson spotted a first edition of Putrid Scum, Kilodney’s takedown of the publishing industry. “I need to read that book,” Stechyson thought.

Today, six years later, he has assembled a rough cut of the first full-length documentary about one of Canadian Lit’s least loveable eccentrics. Stechyson is planning a GoFundMe campaign to finish the film, having weathered Kilodnean setbacks. Government financing bodies turned him down. So did R. Crumb, the legendary Zap Comix illustrator who once blurbed Putrid Scum (“The life he describes is so depressing. But I couldn’t stop laughing”), and urged Stechyson to make his film, but declined to be in it. “It’s like the curse that looked over the hapless life of Crad Kilodney has been passed on to you somehow,” Crumb told Stechyson, who is eager and friendly and therefore the polar opposite of Kilodney. Even W. P. Kinsella, another Kilodney fan, died just as Stechyson was scheduled to interview him. Bohemian artistic misfortune – the talented but unhappy artist fighting the callow, profit-minded establishment – was apparently contagious.

But Stechyson stuck with it because he wanted to answer a particular question: Was the curmudgeon’s legendary unhappiness real? Yes. Or was it an act Kilodney put on for posterity? Also yes. If you intentionally create a life that specializes in rejection and unhappiness, how rejected and unhappy can you really be? And isn’t that more interesting than a life of mere success? Possibly.

Stechyson’s one stroke of luck was the Crad Kilodney Literary Foundation – an unexpected legacy from a writer who plugged his books on street corners. Five minutes after leaving a query on its website, he received a call from Lorette Luzajic, the self-appointed keeper of the Kilodney flame. “Crad believed in fate,” Luzajic told Stechyson. So when she discovered Stechyson lived across the street from the foundation, in midtown Toronto, that was the sign she needed to grant him access to the Kilodney secrets.

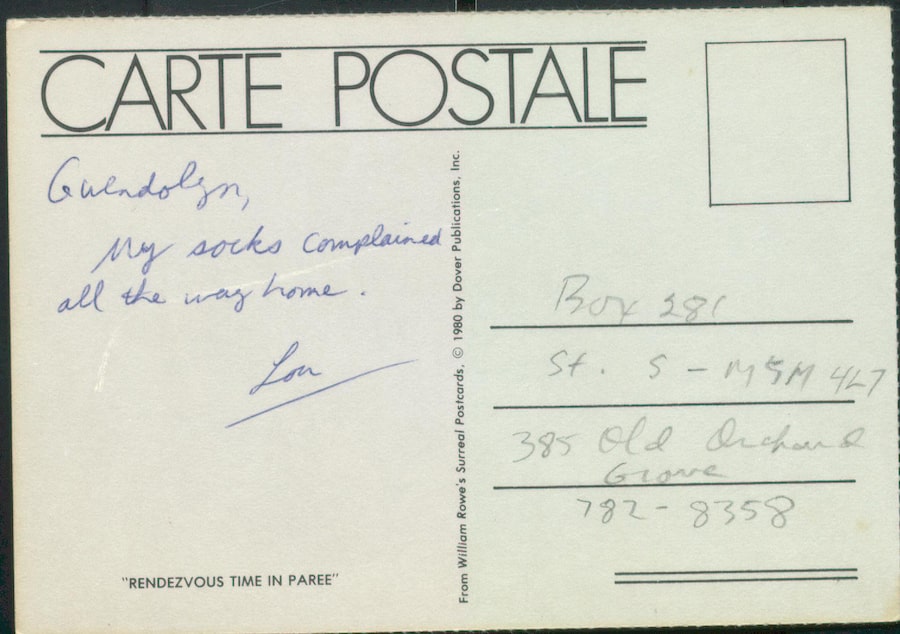

And what secrets they were. Kilodney left his papers to the Thomas Fisher Rare Books Library at the University of Toronto: 30 boxes, or about five metres of files of compulsively organized diaries (hand-written single spaced high-school exercise notebooks), daytimers, letters, reviews, carefully preserved rejection slips, longhand and typed (in duplicate) drafts of his books, plus meticulous daily sales records (day, time, location and weather), stretching over 20 formative years of Canadian culture. Among their revelations were letters attesting to the famous loner’s secret love affair – this is Stechyson’s scoop, dear reader – with the acclaimed poet Gwendolyn MacEwen, with whom he was still involved when she died of alcoholism in 1987 at the age of 46. Kilodney also left the Fisher Library at least $500,000 – not bad for a writer who flogged his fables streetside. He was famously frugal, living for decades in the same tiny, book- and record-stuffed attic hovel in a run-down mansion-turned-rooming house at Isabella and Sherbourne Streets in deepest downtown Toronto. After he gave up selling on the street, in the late 1990s, Kilodney began to trade penny stocks, for which he had a talent.

But the greatest gift Kilodney left behind was his understanding of his value as a character in Canadian literary history. He arrived in Toronto in 1976 as a draft dodger from Queens, N.Y. His real name was Lou Trifon. The son of Greek immigrants, he earned a degree in astronomy, but went to work as an editor at a vanity press, and as the first unsolicited writer to be published in National Lampoon, the humour magazine. (The origins of the pseudonym Crad Kilodney are a mystery to this day.)

Gwendolyn MacEwen signed title page from book, Afterworlds.Handout

Once in Canada he followed the advice of his hero, Henry Miller, which was to avoid any thought of “literary standards” and “give us, in his own language, the saga of his woes and tribulations.” Putrid Scum, Kilodney’s magnum opus, is the compulsively turgid story of a writer trying to do that. “One day it came to him,” the narrator recounts: “he would publish small books of his stories and sell them in the street. He would find his audience by wearing signs that were shocking, amusing, or mystifying and just waiting patiently for his audience to come to him, one at a time and a few each day.”

That process turned out to be a form of slow death. The archives are packed with evidence that Kilodney knew he wasn’t the greatest writer, but that he might be the embodiment of resentful, success-starved late-20th-century literary bohemianism. He addresses his “Dear Future Biographer” in the margins of his manuscripts, prolonging his irony beyond the grave. “I nevertheless was possessed of a conviction,” he writes of his daily despair, “that this was all going to be very important some day.”

To hasten the process, he shamed the literary establishment into recognizing him. In 1989, rejected one too many times by the CBC’s annual short fiction contest, Kilodney retyped classic short stories by famous authors (Kafka, Faulkner, O. Henry) and submitted them under aliases. The stories were all rejected by Robert Weaver, the CBC’s all-powerful literary poohbah, whereupon Kilodney gleefully revealed the hoax to the media. His point: literary fame was subjective and arbitrary, a product of personal preferences within a cultural establishment – ”a circle of dogs sniffing each other’s [insert appropriate but unprintable detail of canine anatomy].” But Kilodney was devastated when Weaver later banned him from attending MacEwen’s invitation-only memorial service.

Like stand-up comics, satirists tend to be angry, and make people angry. Kilodney was well-read, highly intelligent, often funny, unafraid of seeming racist – he kept letters he was sent by Ernst Zundel, the Nazi sympathizer – frequently sexist and always politically incorrect. But his stories are often too bitter to be affecting: His characters feel little else, and so the reader doesn’t either.

He was less guarded in his diaries about his underground affair with MacEwen, which lasted from 1983 until her death. Judging from their letters, they were deeply and desperately in love. “She was way funnier than I imagined her to be, which I figure was part of the attraction,” Stechyson says. She was way more successful, too. A prodigy, she produced two novels, six volumes of poetry, several plays and won two Governor-Generals awards. A park is named after her in Toronto’s Annex neighbourhood. She was also seven years older than her lover, and, by the time she met him, a raging alcoholic. Kilodney’s loneliness was unremitting, but that didn’t stop MacEwen from staying away from him, whether to write or drink. “Gwen and I went to bed, but she said she felt too tired to make love,” Kilodney scribbles one evening in his journal. “I am disappointed but accept the situation generously.” Later, MacEwen gives him a haircut but talks too much, and he snaps “just do it,” whereupon she leaves the apartment, without telling him. He then sends her a note: “Thanks for the disappearing act.” His mood goes dark (“even thought about killing myself or getting a job, which would be about as hard”), but he decides instead to set up his books and sign on Bedford Road, “hoping Gwen might pass by.”

Anthony Stechyson and Margaret Atwood on street.Handout

“I think Gwen and Crad would have had a lot to talk about,” the writer Margaret Atwood, who knew both of them, told me the other day. “Like, how rotten everybody was [to both of them] by that time.”

MacEwen encourages his writing – “That’s the Crad Kilodney voice! The other voice was Lou, not Crad” – but she’s skittish. She lets him store some stuff in her house, but never lets him move in. For months after her death he prays to her every night, “to tell her I was never good enough for her.” There was no mention of any of this in biographical material about MacEwen. “They said she died alone,” Stechyson says. “That’s not true. She had Crad.”

His isolation wasn’t total: He had readers (mostly young writers) and acquaintances. Greg Gatenby, the founder of the Toronto Authors Festival, knew Kilodney, as did Charlie Huisken, the co-owner of This Ain’t the Rosedale Library, one of Toronto’s first alternative bookstores. “All the people in the film came from that counterculture, and they understand that in Crad,” Stechyson says. “It’s that DIY mentality. That’s what I would like to remind people of: Crad took a chance, and we all can as well. We don’t have to be intimidated by failure. Which is not a point of view encouraged by the Canadian literary establishment.” We celebrate success, not effort.

By the end of his stint on the streets Kilodney was recording the bitter details of his failures as triumphs. He sells 522 copies of his novel Excrement, which earns him $3869.65. One July his total sales are $191. Even his rejections become statistics: number of times ignored by [well-known writer] June Callwood, 15 (approx.); number of times sexual intercourse in past year, 0. He writes at night, never sleeps more than five hours, and swallows 190 tranquilizers and sleeping pills a year; his feet ache from standing and selling all day. By the mid-1980s he has sold 27,000 books, with one refund. His occasional sexual companions are never more than first names: Carol, Pam and Glenda, an older, wealthy and very prim Scot. “She looked like the sort of public-school principal you always secretly wanted to see naked.” But his certainty of judgment never wavers: “Likelihood of my posthumous fame: 98%.”

The crack of inauthenticity in his project, of course, is that he wanted to be famous for disdaining fame. “The irony is that Crad, although playing the role of the perennial outsider, wanted to be an insider, too,” Stechyson says. The attention span of passersby in the street is too flickering to fuel the long-distance goals of a writer, and their callousness defeated even the iron-hearted satirist. Atwood – one of the most famous and successful writers in the world – agreed to appear in Stechyson’s movie, gamely wearing a placard and trying to sell her books on Bloor Street in Toronto in June, 2017. “She stood there for an hour, wearing a sign that said ‘No-Name Canadian Writer,’ and no one knew who she was,” Stechyson says. A young woman finally recognized her, but said she’d borrow her books from the library. “It’s always chancy doing a thing like that,” Atwood said, “because people just think you’re slightly crazy.”

Stechyson finally decided it was not the establishment that stood between Kilodney and success, but Kilodney. “He let the street affect him. He started out wide-eyed and bushy-tailed. And the days when no one stopped, it rotted him from the inside out.” If you are going to make a career outside the mainstream, you can’t tie your satisfaction to mainstream success. “He and Gwen were both very smart,” Atwood said. “And there are a lot of people like that in the world: They’re very smart. But there’s no part of their smartness that engages with what’s available.”

Kilodney’s only close friend was Lorette Luzajic, a writer, painter and editor of The Ekphrastic Review.Handout

In the last eight years of his life, before he succumbed to a third bout of pipe-induced oral cancer in 2014, at 66, Kilodney’s only close friend was Lorette Luzajic, a writer, painter and editor of The Ekphrastic Review. Luzajic – who describes herself as “pretty eccentric too, though in a completely different way” – had written a story about Kilodney; he got in touch to tell her “he was impressed it had no typos.” They were never lovers, but ate dinner together once a month, alternating between one another’s apartment until Kilodney’s last nine sickly months, when Luzajic visited him every day, even on his deathbed. Shortly after they met, she bought him a second-hand computer on Kijiji, but was rebuffed: instead he began to use a local internet café to type up the longhand draft of his last project – “a rewriting of Shakespeare, for white trash.” She got him out of his or her apartment precisely three times before he moved to a hospice to die: once to visit a museum, once to eat at a Swiss Chalet and once to a stock promoter’s convention, to which Kilodney wore a suit, and called himself Lou. “But he seemed to be making that character up,” Luzajic says. His most authentic identity, she feels, was the one he describes in Putrid Scum: “ ’my life is a satire of a writer’s life.’ And whether he made himself into that, or whether he was that, the difference is negligible. Yes, in a way, the whole thing was constructed. But I don’t think it was a fake. For such a logical guy, he really believed in fate. And his fate was that character. Not everybody gets to be happy.” Someone has to pay attention on the way down into the obscuring darkness.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.

Ian Brown

Ian Brown