The Globe and Mail

On Monday, one of five books will be named the winner of this year’s Scotiabank Giller Prize. Ahead of the (much smaller than usual) gala, we asked the five authors on the shortlist a short list of questions.

Nathan Howard/The Globe and Mail

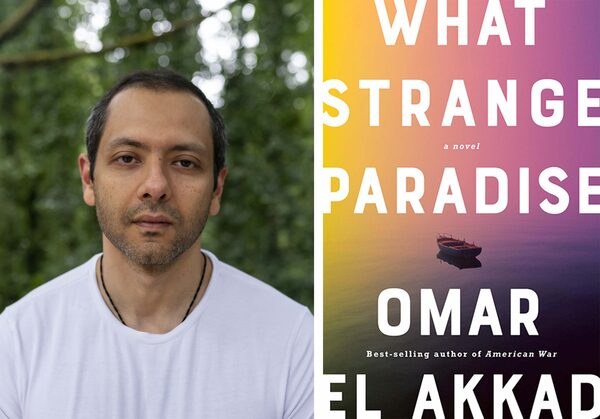

Omar El Akkad, What Strange Paradise

Born: Cairo, Egypt

Lives: Portland, Oregon

Age: 39

The former Globe and Mail journalist imagines a boat full of refugees fleeing difficult lives for what they hope are better options in the west. When the boat’s journey ends near a Greek Island, the story unfolds through the eyes of Amir, a nine-year-old Syrian child on board the doomed vessel.

Are you able to recall the spark, if there was such a thing, that led to this book? Its genesis?

I was on assignment in Cairo in 2012, covering the aftermath of the Arab Spring. I was riding around town one night with an old high-school buddy and we were having a fairly pedestrian conversation – he was complaining about how the rent was too high. At one point I asked him what the rent was for an apartment in his building. He said, “Do you mean the locals’ price or the Syrians’ price?” It turned out that, because there had been a recent influx of refugees from Syria, landlords were taking advantage and charging them upwards of three times as much for an apartment. “I mean, what are they going to do,” my friend said, “go somewhere else?” I was struck by the casualness of it all, the offhand cruelty. It would take years for that first reaction I had to transform into the book What Strange Paradise eventually became, but that’s the closest I have to a genesis moment.

Can you tell me about something that was particularly challenging for you as you were writing this?

I spent about a year and a half working out the structure of the book, and that time was probably marked by more failure than success. At one point I ended up writing and then deleting a series of monologues from the points of view of the passengers on a migrant ship, which together represented something like a third of the manuscript at the time. That wasn’t an easy decision to make, but the pieces weren’t working, so they had to go.

In what way, if any, did COVID-19 have an impact on this book?

I finished writing and editing the book during the pandemic, and the slow mental grating of prolonged isolation eventually made it impossible for me to be able to judge the quality of the work. I just got to a place where my anxiety was seeping into my decision-making ability, and I didn’t trust myself to accurately assess what the book needed. Thankfully I had a close circle of trusted readers – my agent and my editor and a few close friends – who I could turn to. I’m not sure I would have finished the novel otherwise.

Is there anything in your book that might be perceived differently as a result of the pandemic?

The book’s central villain is a xenophobe and an isolationist. At one point he says, “you can’t bet your future on work that requires the coming together of people, not now, not with the world the way it is. The days of people coming together are ending; this is a time for coming apart.”

That line, and to a certain extent the character as a result, has been read very differently in the context of the pandemic.

Can you tell me about the book’s dedication?

Sonny Mehta was the head of Knopf until his death two years ago. He’s one of the finest editors who ever lived and the man who gave me my career as an author. He’s responsible for publishing my first novel, American War, and What Strange Paradise, which he acquired and began editing shortly before his death. Getting to work with him for those few years is the greatest piece of good fortune I’ve ever experienced in my career. He made me a better writer and I miss him dearly.

Now that the book has been out for a while, I wonder if you’ve received any feedback from readers who have their own refugee stories.

I have. It’s a privilege I didn’t expect and probably don’t deserve, to be entrusted with the sorts of experiences that, in many cases, constitute the darkest and most treacherous periods of people’s lives. Whatever its merits or faults, What Strange Paradise is a book that reads very differently depending on what experiences the reader brings to the story, and I think some of the most generous readings have come from people who’ve brought with them some harrowing experiences.

How – if, in any way – did writing this book change you?

I had to decide, early on, how much of the book was going to exist beneath the surface-layer story, buried in places and in ways that might go unnoticed. I was scared of writing that kind of novel, scared of what readers who liked the worldbuilding and action in American War might think of something so different in form and style. I still don’t know if I made the right decision, but I’m not scared of making these kinds of decisions anymore.

Find the Giller shortlist nominees in your neighbourhood’s Little Free Library

Handout

Angelique Lalonde, Glorious Frazzled Beings

Born in Murrayville (Langley), B.C.

Lives now: north of Hazelton, B.C.

Age: 42

Twenty-one stories are divided into four sections: Homemaking, Housekeeping, Home Breaking and Homing. Characters include a woman who is uncomfortable with her mother’s decision to try online dating, a boy born with fox ears, and a man named Pooka who makes art out of old carpets.

Are you able to recall the spark that led to this book? Or any of the individual stories?

I can talk about the spark of how the book came together as a collection. I’ve been writing for quite a while and just started publishing in 2018 with my first story, Pooka, which won the Journey Prize. And when I started to think about making a book, I started sifting through [my stories] and I realized once I read through everything and gathered it together, I was writing about home and the theme of home: how home is made and then how we keep home, the domestic everydayness of home and how home is sometimes a really difficult and a kind of tragic place to be. That home breaks apart.

Can you tell me about something that was particularly challenging for you as you were writing this?

On a practical note, the really difficult thing for me is the fact that I am a mother of two young children and I work at another job outside of that. So finding time to write is always a challenge and [so is] finding time to focus and have the ability to dig into things. My son is three and my daughter is six. I also work and garden and grow quite a lot of our own food, so life is busy. Maybe that’s a part of it; the busyness kind of propels the work forward.

I wanted to ask you about reading reviews, because we see in Pooka how negative feedback can stop an artist in their tracks.

I don’t think I have really ever read a review of my work, because I don’t think there are that many out there. It would be hard to read a negative review, but at the same time, I think that’s just part of the process. I’ve definitely felt a little bit of anxiety about putting my work out there, which is why I didn’t do it for a long time. But I think part of life as a grown-up is just figuring out which feelings are yours, and which feelings are someone else’s. I think the work that I create is the work that I create, and what other people think about that isn’t going to influence that for me. So it probably would hurt. And then I would find a way to move on and just keep working.

Can you tell me about the book’s dedication? (“For all the glorious beings that have gifted me with parts of their stories.”)

There’s been so many beings that have been part of my life throughout the time that I’ve been alive and they all show up in the stories in different ways. So, I wanted to find a way to be inclusive to humans, more than humans, non-humans, to kind of acknowledge all of them.

I know people who write short stories are asked this all the time, but when you have a story, how do you know it’s a short story, and not a novel?

I think that directly relates to having kids for me. I don’t even understand how a mother – or fathers who do a lot of care – could write a novel. I’m very impressed by that. I just can’t hold a thread for that long. I love finishing things and I’m so grateful when a story is done. It gives me a sense of accomplishment, so that I can finish something and move on. Of course I go back to them multiple times. And then I can work on multiple things at once so if I’m not feeling one story when I sit to write, then I move on to another and I go back. I think that’s the way that my creative energy works as well, so that I’m not just stuck in one story. So for me it’s the only writing that feels possible right now. I do have an idea for a novel that I’m starting now, and we’ll see.

You finally publish the book and it’s on the Giller shortlist. What has this done to your life?

My life feels totally overwhelming right now. I haven’t had any time to process it. My book was released on September 7 and the longlist was announced on the 8th. It’s really surreal. I live a rural life; my day-to-day life is pretty small. All of a sudden it’s kind of like this explosion of this whole world opening up. Of course I’m deeply, deeply honoured and it feels amazing and beautiful. And at the same time it feels otherworldly and I don’t really know how to bring it back down to earth.

Handout

Cheluchi Onyemelukwe-Onuobia, The Son of the House

Born: Enugu, Nigeria

Lives: Lagos

Age: 43

Two women who have been kidnapped together learn each other’s life stories. Nwabulu’s many tragedies begin with the death of her mother in childbirth. Julie, from a more privileged background, has her own difficulties. What they share in common is the plight of being women in a culture where men have all the power.

Are you able to recall the spark that led to this book?

Yes, I remember distinctly how the idea came to me. Of course, it then went through several iterations and versions before it came full circle. When I was finishing my doctorate at [Dalhousie University], I told myself that I was going to write a book right after, but I was stumped. Then my mom told me a story about someone we had grown up with. And I thought: this is what I grew up with. I grew up with my mom having friends who, when they broke up with their husbands, weren’t allowed to keep their children, because in our culture we think the children belong to the men. One particular situation was so close to us. She had five boys. When they broke up, she had one that was maybe a year old or a little younger. She was allowed to keep that one while the man kept the other four boys. But when he was about five, six years old, they came for him and they took him.

Have things improved for women in Nigerian culture?

I was recently doing some work where I was doing what you would call a gender profile for Nigeria. If you had asked me before I did that, I would have said yes. Yes, I am a woman in Nigeria, I hold a doctorate degree in law, I taught at university. Some Nigerian women are doing wonderfully well. But, like I said, doing that gender profile made me think, looking at a different perspectives. Looking at the housemaid for example. There are women for whom things haven’t really changed and they are still very much in the majority. Without taking anything away from those who have accomplished things and those who are showing that we are and can be forces to be reckoned with, we still have work to do. Some ways to go. Across different indicators like wealth, political participation, education, women are still kind of lagging behind.

I read this book as a strongly feminist text – not preachy or didactic, but very powerful. Is that fair?

I wanted to show what it currently is like, while hoping that leaves room for people to think about what it could be like if we did things differently. I come from a very strong place of gender equality, saying we can and will be more. It’s a matter of time. It’s evolving. It’s maybe evolving a little more slowly than some of us would like.

Can you tell me about something that was particularly challenging for you with this book?

I had a lot of challenges trying to get the book out into the world. There were times I would come back to it to try to see what it was that I was missing that was leading to all the rejection.

How long did it take to get it published?

I wrote it over the course of I would say 18 months in total. And then it took me another four years to get a yes. I kept sending it out. I sent it to agents. And when I didn’t get agents, I sent it to small publishing houses that would take books without an agent. And I eventually succeeded in getting almost at the same time two publishers – one in Nigeria and the other in South Africa. It was my South African publisher who eventually sent it to Scott [Fraser] at Dundurn Press. He loved the book and brought it home to Canada.

Can you tell me about the book’s dedication?

It’s dedicated to my parents. My father and mother have always said that I could be and do just about anything. It was so fulfilling to be able to dedicate a book to them while they are still here on this planet.

Caio Sanfelice/Handout

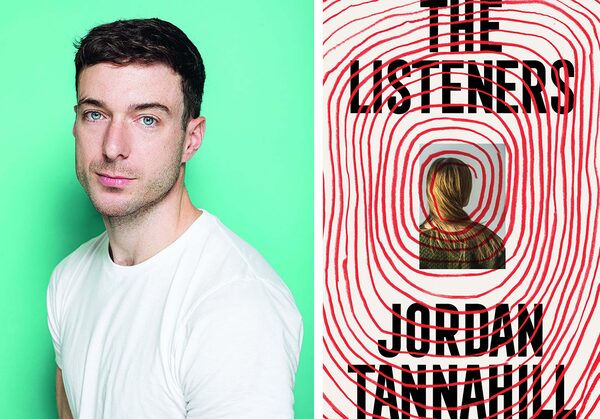

Jordan Tanahill, The Listeners

Born: Ottawa

Lives: London, U.K.

Age: 33

In the Governor-General’s Award-winning playwright’s second novel, a high school English teacher in a southwestern U.S. suburb starts to hear a low hum. Her husband doesn’t hear it, nor does their teenage daughter. But one of her students does. When she finds a community of other Hummers, she finds some solace – and trouble.

Are you able to recall the genesis of the book?

I first became aware of the hum about seven or eight years ago when I read an article without it. I don’t hear it myself, but I was reading articles about hums – actually that had been reported here in Canada, the Windsor Hum being one. And there’s literally thousands of different hums throughout the world. The thing that really captured my imagination was the enduring mystery as to what these could be. Sometimes only a single person in the household could hear the hum, and … that would be potentially a very isolating experience for them, to not even have the ability to really talk about it with their family.

Why was this a novel and not a play?

Initially I did write the play for the National Theatre here in the UK. It was workshopped and it was a great pleasure to hear these characters become these fully fledged human beings. But it was just too massive. It would have taken at least four-and-a-half hours to stage. And I knew it would have to be halved in length in order to make it a reasonable production. I think my instincts as a playwright are still quite evident in how voice-driven the work is, how dialogue-driven.

In what way, if any, did COVID-19 have an impact on this book?

The pandemic gave me a major opportunity, first of all, to finish the book, but also a chance to reflect on the themes of the book in a different light, I suppose. As I was completing the book, 5G towers were being burned across the U.K. because of their believed association with propagating COVID-19. The pandemic has intensified an almost paranoid ennui, if you will, and also this kind of longing for connection and community. This need for touch, or the inability to touch. I think that longing for community that permeates the book was definitely an echo of particularly early lockdown sentiments.

You’re Canadian, you live in the UK. Why did you set the book in the U.S.?

There’s certainly a version of this book that could have been set in Canada. I think the States has this kind of intersection of faith mania and conspiracy culture. All these things feel larger there, I suppose. The ways in which truth or, specifically, untruth has been weaponized in political culture there, and ways in which conspiracy culture has been mainstreamed. The way in which faith operates in society and in politics and in everyday life. It feels so much more present there. And so it just made sense.

How – if, in any way – did writing this book change you?

I think it taught me the value of staying with a story for years. It took me a long time to figure out how to tell this story and what form best to tell it in. It taught me to take time to rewrite, rewrite, rewrite. Really for the better part of the decade I’ve been trying to figure out how I’m going to tell stories of the hum. That’s probably the thing I’ll take from this process more than any other.

Can you tell me about the dedication?

James is my ex-partner who I am still very, very close to and I love very much. He is a voracious reader and great thinker and read many drafts and offered very thoughtful and substantial feedback throughout the process. I feel like there could be no other dedication than to him.

Christopher Katsarov/The Globe and Mail

Miriam Toews, Fight Night

Born: Steinbach, Manitoba

Lives: Toronto

Age: 57

When nine-year-old Swiv is expelled, her grandmother Elvira takes on the role of teacher while Swiv’s mother, who is pregnant, keeps going to work at the theatre, where she is rehearsing a play. The lessons Swiv learns from Elvira transcend math and science. They are about something much more vital: how to live a full and meaningful live.

Are you able to recall the spark, if there was such a thing, that led to this book?

The birth of my first grandchild, the instant I became a grandma. And then the arrival of all the other grandkids! I wanted to make them laugh. I wanted to tell them about my mother, their great-grandma, and I wanted to encourage them, because life is not easy, and they will have hard questions about their family and they will suffer at times. I wanted to create a kind of fast-paced fiction around all of that, told from the point of view of an anxious but funny kid.

Can you tell me about something that was particularly challenging for you as you were writing Fight Night?

Fight Night was a joy to write. A little bit every day. The challenge was, of course, staying in character, getting Swiv’s voice just right, as an “unreliable narrator” and still conveying enough information about things, the other characters, to the reader.

In what way, if any, did COVID-19 have an impact on this book?

Well, I started it before Covid hit. But I think being able to put myself into that world, Swiv’s world, while I was writing, a world of raucous travel and movement and people and contact with others, was really a relief, and it felt exciting. And maybe that kind of exuberance somehow made it into the book.

How is your mother feeling about the attention? [Elvira the character is based on Toews’s mother.]

Oh, she’s cool. It’s just a moment in time. She takes it all with a grain of salt, reminds me that we need to keep things real and free-wheelin.’

These interviews have been condensed and edited.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.

Marsha Lederman

Marsha Lederman