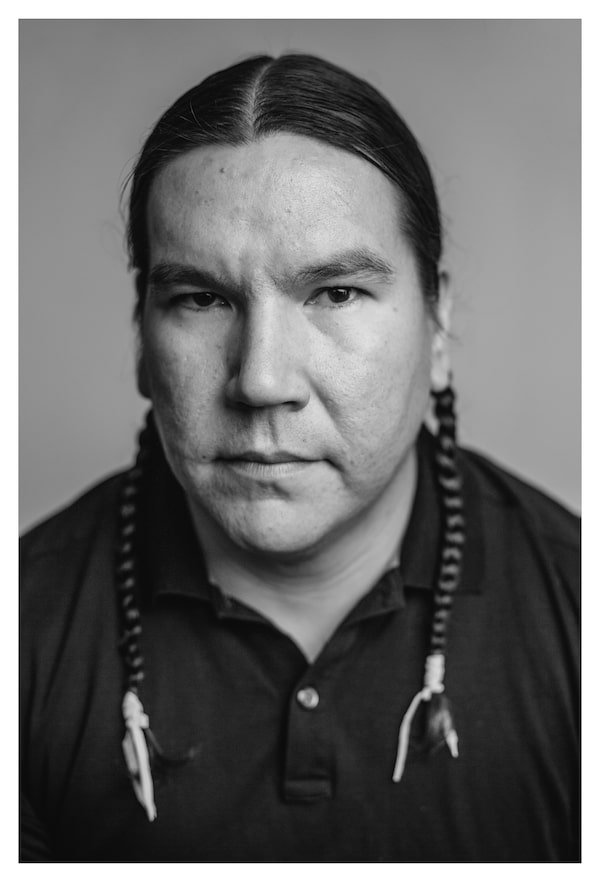

Waubgeshig Rice.Rey Martin/ECW Press

Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice.

Waubgeshig Rice is an author and journalist who splits time between Ontario’s Sudbury and Wasauksing First Nation. When he’s not working at the CBC and hosting the CBC radio show Up North, he is writing. First, there was the short-story collection Midnight Sweatlodge in 2011. He followed that up in 2014 with his first novel, Legacy. His latest is Moon of the Crusted Snow (ECW Press), a thriller set in a snowbound northern Anishinaabe community, where a postapocalyptic reality slowly creeps its way through the band. Here are the books that have most influenced Rice throughout his life.

What did you read as a kid?

Growing up on the rez at a time when my family and community were really reconnecting with Anishinaabe traditions, spoken storytelling had a bigger influence on my upbringing than books did. Still, books were a big part of my childhood. My parents encouraged reading from a very early age. We didn’t have a television, so I have fond memories of both my mom and dad reading to me and improvising stories at bedtime. Some of the books on the shelf were the classics by Robert Munsch like The Paper Bag Princess, and of course, Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are.

While imaginary worlds and characters really intrigued me, I was more curious about the real world around me and I had a pretty intense thirst for knowledge as a little kid. So the book I recall the most vividly is one called Things to Know by Richard Scarry. It’s a pretty straightforward, almost encyclopedic illustrated book of facts about everything from the seasons to plants to school elements. In hindsight it’s not the most profound example, but I was also reading newspapers regularly at around the same time, so maybe I was destined to become a journalist before I became an author.

What did you read in grade school?

We read the classics at our school on the rez, such as Two Against the North and Charlotte’s Web, and I really enjoyed getting to know the novel as a storytelling vessel. Reading fiction eventually became a fun habit for me and I started getting into books that were outside the curriculum on my own. My dad was a big science fiction fan back then, so we had some of the major titles by authors like Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke kicking around the house.

The one that had the biggest impact on me, though, was The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells. I can’t remember exactly how old I was when I picked it up – I must have been 10 or 11 – but I was hooked by the premise and tore through it. The idea of aliens invading Earth and causing chaos scared me, but I was also fascinated by the possibility of creating otherworldly scenarios and speculative tension in written storytelling. At that age I was also becoming more aware of the violent invasion my Anishinaabe ancestors endured, so even then I could draw basic parallels between fictional and real apocalypse.

What did you read in high school?

I went to high school off-reserve, where books by Indigenous authors were totally absent from curricula back in the 1990s. Still, I enjoyed the books on the English class lists, and by the time I was in Grade 12, we had a teacher who devoted a big chunk of the semester to dystopian novels like Brave New World, 1984, and Fahrenheit 451. I loved all of those, again, because they speculated a world of chaos similar to what my ancestors had experienced. But the books that shaped me the most were the ones I read outside of the classroom.

Fortunately I had an aunt who recognized my developing passion for fiction, and she gave me books for my birthday and Christmas by Indigenous authors like Richard Wagamese, Lee Maracle, Thomas King and Louise Erdrich. The stories in these books opened my eyes to an entirely new storytelling realm. For the first time I had seen my experiences reflected on the page in front of me. The one book that resonated most strongly, though, was one of the first ones she gave me – a collection of three novellas by Jordan Wheeler called Brothers in Arms. Each of the stories centred on young Indigenous people, which is something I had never encountered. It further inspired me to write my own short stories and some of those eventually became my first book, Midnight Sweatlodge.

What did you read in university?

I studied journalism at Ryerson University and a six-credit English course was compulsory every year as part of that program. So I had the opportunity to read a lot through those four years, and some of those books really hit home, like Louise Erdrich’s Tracks and Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Moving from the rez to the biggest city in the land was a little overwhelming and in most of my classes, I was the only Indigenous person. So I felt like an outsider in a lot of ways and that’s why I really connected with Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. It follows an unnamed protagonist from the American South to New York, where he struggles to find belonging as a black man and has to navigate through black communities that are stepping up efforts in a fight for rights. My initial years in Toronto weren’t as revolutionary a time for Indigenous peoples as in the book, but Invisible Man helped guide me into the kinship between Indigenous and black communities.

What are you reading now?

Right now I’m about to get back to a big stack of books I’ve been meaning to read for a while now, including Heartbreaker by Claudia Dey and Jonny Appleseed by Joshua Whitehead. The book I most recently finished was Trickster Drift by the mighty Eden Robinson. It’s the second in a trilogy about a teenager named Jared who contends with a dysfunctional family and upbringing while trying to keep spiritual influences at bay. Trickster Drift finds him in Vancouver, where he’s trying to stay sober and get his education, but because of his role as a bridge between chaotic real characters and weird supernatural ones, he keeps getting pulled in all kinds of directions. It’s written with Robinson’s typical humour and depth, and provides a fun and compelling window into the young urban Indigenous experience on the West Coast. A book like Trickster Drift will inspire more and more young Indigenous people in Canada to share their truths in the written word, which is what we need more of in the modern literary realm.