Holocaust survivor David Schaffer and graphic novelist Miriam Libicki examine documents from Schaffer's life at his Vancouver home. A new project aims to bring the stories of Holocaust survivors to younger audiences through the graphic novel medium.Jennifer Gauthier/The Globe and Mail

One of Miriam Libicki's sketches of David Schaffer.Jennifer Gauthier/The Globe and Mail

The refrigerator door in David Schaffer’s modest Vancouver kitchen is plastered with photographs of his family, mostly his grandchildren. There are nine of them; seven in Toronto, two in Vancouver – all of them miracles.

Stuck with magnets to the side of that fridge are various phone numbers, instructions about how to recognize a stroke or heart attack and lighthearted, motivational messages. “Don’t Kvetsch Be Happy!” is the boldest among them. And a bit below it, in bright red, “If you obey all the rules you miss all the fun.”

A couple of hours after I notice these sweet little messages, I hear Schaffer, who turns 89 in February, use some of those same words. He is explaining to an artist, film crew and an academic, in his precise and philosophical Yiddish-accented way, what not obeying the rules has meant for him. It has meant this kitchen, those grandchildren, his life.

“If we had followed the rules,” he says, “I would not be here to tell the story.”

Schaffer is telling his story of surviving the Holocaust as part of a Canadian-led international project that involves the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam and other institutions in the Netherlands, Canada, Germany, the United States, Britain and Israel. Three graphic novelists have been teamed up with survivors on three continents to create three books meant to teach this vital history lesson to high school students in a way that will beckon and penetrate, and not simply horrify.

It is the brainchild of Charlotte Schallié, chair of the department of Germanic and Slavic Studies at the University of Victoria. As part of her work in Holocaust studies, Schallié has interviewed many survivors. These testimonies are essential, she knows. But for educational purposes, she wanted to create something that would do more than serve as archival proof; something that would jump out at students and get through to them, make them want to learn about this part of history, and the implications for contemporary human rights. She wanted something they could consume on a more interactive level, too.

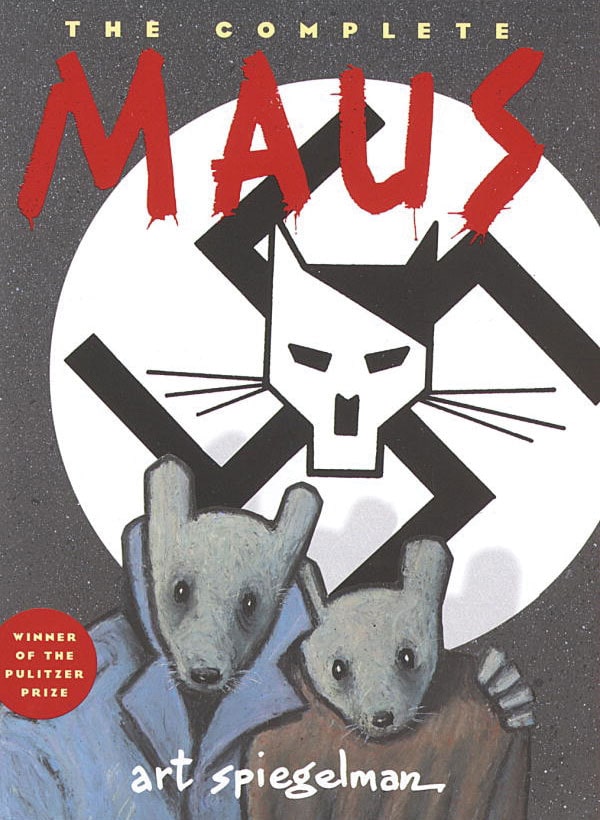

The Complete Maus, by Art SpiegelmanPenguin Random House

“I felt what are we doing with these testimonies? They’re ending up in archives and how do we continue to make them relevant?” Schallié explains in an interview, making it clear that eyewitness testimonies are vital and valuable. But, she added, “I felt we need to find something else, new approaches to testimony collections, telling the story of the Holocaust in a richer, deeper way, and more meaningful way.”

Schallié has a son, now 13, and at some point while pondering this, she took note of his passion for graphic novels. And she thought about Art Spiegelman’s seminal graphic novel, Maus, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992, and the strong impact that Holocaust story has consistently had on her students. Schallié had her idea.

Each of the three artists has the freedom to explore their own vision in the three graphic novels, which will be available digitally in 2022, along with supplementary educational materials. Schallié hopes the books may be published in physical form, too.

The project addresses another issue related to this field of historical study. Most of the visual material we have from the Holocaust is photography produced by perpetrators, Schallié explains. With artists creating illustrations drawn from the memories of the victims, a different image – one from the survivors’ perspective – can emerge.

While meeting with David Schaffer, graphic novelist Miriam Libicki sketched some early ideas. “I’d really like to do justice to David’s great storytelling ability and the very visual and sensory details,” she says.Jennifer Gauthier/The Globe and Mail

For about four years, Schallié, whose own grandmother was murdered at Auschwitz, has worked to find partners for the project. They now include the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (which will help create a teacher study guide and lesson plan built from survivor testimonials and is planning a visual storytelling conference at the museum), the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre and other international institutions (such as the aforementioned Anne Frank House). Then, Schallié had to find funding, and finally, survivors and artists.

This was a race against time and memory. Many of the still-living survivors are suffering from some type of memory loss. But with help from her partners, Schallié was able to find storytellers for her urgent project on three continents.

At a meeting in Achterveld, Netherlands, from left to right: Graphic novelist Gilad Seliktar and German-born Holocaust survivors Nico Kamp and Rolf Kamp. Achterveld is among the locations the brothers were hidden during the Second World War, in this case by a couple who ended up emigrating to Winnipeg.Charlotte Schallié/The Globe and Mail

A drawing by Gilad Seliktar depicts the illustrator along with Rolf Kamp as they examine documents related to Kamp's Holocaust survival experience.Gilad Seliktar

In Amsterdam, German-born brothers Nico and Rolf Kamp, who were hidden in 13 places during the Second World War, are working with Israeli comics artist Gilad Seliktar, whose maternal grandmother lost her entire family – they were murdered at the Treblinka death camp – while she managed to flee Poland to safety. There is a Canadian connection here – the couple who hid the Kamps for the longest period of time, Regina and Hendrikus Traa, emigrated to Winnipeg in 1954.

In Israel, survivor Emmie Arbel, who was born in The Hague, is working with Munich-based graphic novelist Barbara Yelin. Yelin, who is not Jewish, wrote her 2014 graphic novel, Irmina, after learning that her late grandmother had been a Nazi sympathizer.

And Schaffer is working with Miriam Libicki, who is based in the Vancouver area and whose paternal grandparents survived the Holocaust.

Libicki, 38, was born in Columbus, Ohio, and moved to Vancouver in 2002, where she attended Emily Carr University and the University of British Columbia. Her publications include a book of graphic essays, Toward a Hot Jew; the autobiographical Jobnik!: An American Girl’s Adventures in the Israeli Army; and Ruchie’s Job, about two female prisoners at Auschwitz, which is dedicated, in part, to her grandparents, “whose dry survivor humour I am eternally indebted to,” she writes.

Libicki was the 2017 writer-in-residence at the Vancouver Public Library, and is in France this year on an artist residency at the International City of Comics and Images.

“I’d really like to do justice to David’s great storytelling ability and the very visual and sensory details,” she says.

A 1944 government permission slip allowing the Schaffer family to travel back home to the Bukovina region. Resources were so scarce that officials had to reuse old paper for such documents. In this case, an old letter from 1930 (completely unrelated to the Schaffer family) is crossed out with red pen.Jennifer Gauthier/The Globe and Mail

David (Dago) Schaffer’s story begins in 1931, when he was born in the village of Vama, Romania, where his family lived on a large plot of land on which they grew fruits and vegetables and operated a general store. David was a good student who loved school. But in 1939, a few weeks into Grade 2, he was visited at home by his teacher, who sorrowfully and reluctantly told his parents that as a Jew, David could no longer attend school.

Thus began an unimaginable years-long trauma for the Schaffers – displacement, starvation, beatings, hard labour, humiliation. They hid in forests and slept in barns. They froze, they roasted, they were dehydrated and maimed. There was death all around them. “I cannot count the number of times I was truly afraid for my life,” Schaffer recounts in his memoirs, One Shall Not Be Tested, which was written as part of a Holocaust memoir project at Vancouver’s Langara College.

Libicki read the memoirs before meeting Schaffer. That reading inspired some early images she will likely work with, such as a story he tells about his footwear.

Another travel document on the other side of the old letter. This allowed the Schaffers to travel back to Gura Humorului, Bukovina, the town close to Vama. It is dated September 20, 1944.Jennifer Gauthier/The Globe and Mail

His family exiled and starving, David goes into the wheat fields after the harvest to collect spikes that had been left behind. He is about 11, a growing boy, and has no shoes that fit to protect him from the bits of straw that poke out of the ground and feel like nails on his feet. For protection, he fashions shoes out of rags. But the rags keep falling off, and there is no string or rope. So he uses the only thing he can find to tie his rag shoes to his feet – barbed wire.

There are, perhaps improbably, some big laughs during their interviews. Schaffer jokes a lot; he is a cheerful and optimistic soul, even when telling horrific stories from his wartime childhood, such as being terrified as a Romanian soldier on horseback used his long sword to search his little bag, inside which were hidden a few tobacco leaves – contraband. “You cannot imagine how scared I was and I cannot describe it to anybody,” Schaffer tells Libicki.

Over two days, she listens, takes notes and sketches in her notebook. Schaffer shows her old photos and documents. A documentary crew films the proceedings for another aspect of the multipronged project, and Schallié takes notes and photos with her phone.

Libicki's visit to Schaffer's house was filmed by University of Victoria student Mike Morash.Jennifer Gauthier/The Globe and Mail

The interviews take place in early January, while Libicki is back in B.C. for the holidays. All agree that recent anti-Semitic sentiment and attacks, including a multiple stabbing at a New York rabbi’s home during Hanukkah, have brought new resonance to the project.

"Even though I have survivors in my own family I was like, ‘oh well that’s been done. Maus is the biggest graphic novel in the world. I should go do other things because I don’t want to be just another person who’s just doing just another Holocaust story when a Holocaust story is one of the most famous graphic novels in the English language,’” Libicki says “I think that I changed my mind about that because I do feel it’s more urgent now.”

For Schaffer, the recent headlines have been particularly hard to take.

“I get frustrated when I hear those news and people try to pretend that it didn’t happen or to explain … the guy’s crazy, the guy’s extreme,” he says. “But you know, it’s like a flame. A little burst up and when it becomes a big flame, you can’t quench it any more.”

And as difficult as it is to recount these memories – the interviews leave him bone tired – Schaffer knows how crucial it is.

“This is why I told the story,” he says. “I don’t like to tell the story and it kind of stirs me up. But it needs to be done.”

A little family history: Holocaust survivor David Schaffer shows documents to his grandchildren (top) Aaron, 17, Joelle, 21, (bottom, left to right) Zachary, 9, Joshua, 9, Paulina, 14, and Madison, 12.Jennifer Gauthier/The Globe and Mail

Marsha Lederman

Marsha Lederman