Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.

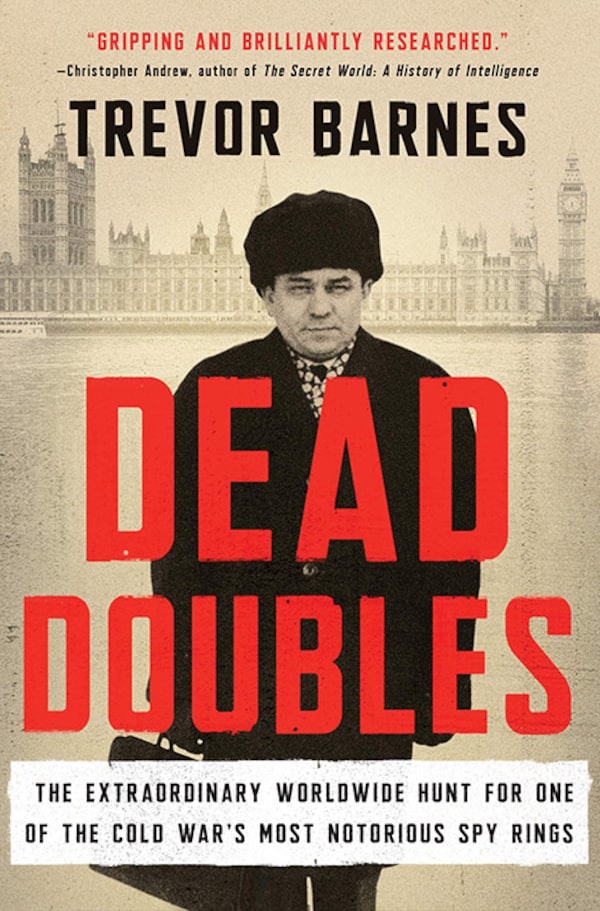

American-born spies Morris, right, and Lona Cohen, known in the West as Helen and Peter Kroger, on Oct. 24, 1969.The Associated Press

It’s perhaps fitting that this year full of paranoia – about threats real and imagined – would see the publication of a trove of non-fiction about espionage and the Cold War. Dare I say there’s even a certain comfort, in a time when mall information boards surreptitiously scan our faces and nuclear scientists get assassinated with remote-controlled weapons, in reading about the analog spycraft of yore: invisible ink, threads on attaché-case handles, hidden panels, goofy codewords, homemade antennas clunkily hoisted onto roofs – all of it fashioned long before Michael’s or Radio Shack existed. On this and other fronts, the following six books have much to offer.

Handout

It’s always a bonus when a book about espionage reads as compellingly as a great spy novel. And with its vivid characters and cliffhanger chapter endings, Ben Macintyre’s Agent Sonya more than fits the bill. “Moscow’s most daring wartime spy,” the Red Army colonel codenamed “Sonya,” was in reality a German Jew born to a wealthy family of left-leaning Berlin intellectuals. After falling victim, like many in her cohort, to the violent injustices of the Weimar Republic, Ursula Kuczynski became a communist in the 1920s, while still in her teens. In the early thirties, she was recruited as a “housewife-spy” by the Soviets while living in an expatriate community in Shanghai. Ideology was just one aspect of the attraction: Ursula was also a thrill-seeker who relished her espionage-led travels her around the globe, which took her from Europe to Asia to the United States and Britain. And to Moscow, naturally.

From the get-go, gender was key to her cover. Prevailing sexist attitudes meant that no one suspected the woman with the babe-in-arms of being a Soviet agent; including, for a weirdly long time, her first husband, Rudi Hamburger, an architect who later became a spy himself (albeit a hopelessly inept one who spent decades in labour camps). During the war, while living in a cottage in England’s Cotswolds with her three children, Ursula played a key role in getting the Allies’ Manhattan Project plans into Soviet hands, activities she perceived not as against Allied interests, which she supported, but as a means of fighting fascism and, to her innocent eyes, levelling the nuclear playing field.

Brilliant but underestimated women crop up throughout Agent Sonya. There’s the volatile American writer and Soviet spy Agnes Smedley, Ursula’s original recruiter; Melita Norwood, “the longest serving Soviet agent on British soil, but also, for many years, the dullest”; and MI5 counterintelligence’s only female agent, the dour Milicent Bagot, whose alarms about Ursula/Sonya fell on deaf ears; willingly deaf in the case of Kim Philby (writes Macintyre, “Only a woman could have seen through Ursula’s disguise”). Macintyre effortlessly juggles a large but memorable cast of characters, injecting welcome but unobtrusive humour into the narrative along the way. If Agent Sonya doesn’t wind up on some kind of screen, there’s no hope for Hollywood.

Handout

Set between 1944 and 1956, The Quiet Americans is a natural follow-up to Macintyre’s book. Despite its chunky size, it also shares many of Agent Sonya’s best qualities: supreme readability, baked-in suspense, wide geographical spread, and vivid characters. But where Agent Sonya is a story of beating the odds – Ursula survived capture in the West, not to mention Stalin’s purges – the four Americans that are the subject of Scott Anderson’s book were, as its subtitle, “a tragedy in three acts,” suggests, less lucky. Edward Lansdale, Peter Sichel, Frank Wisner and Michael Burke set off as idealists to various points abroad to serve a nascent CIA, only to see their missions undermined by cynical political machinations back home, not least by J. Edgar Hoover and Joseph McCarthy. Anderson harnesses the men’s fates and disillusionment to show how anti-communist rhetoric used to mask the same colonialist impulses the U.S. ostensibly decried became “just one more political hustle, a sales pitch that sold well to the gullible or frightened or overly trusting.” It’s well-nigh impossible not to see parallels between the world of The Quiet Americans and recent U.S. politics, where Red-baiting remains a go-to Republican strategy.

Handout

For those more interested in the nitty gritty of spycraft, Trevor Barnes’s Dead Doubles will be catnip. Like the previous two, Barnes’s book employs considerable narrative flair as well as maps and photos to explain how MI5 cracked a Soviet spy ring operating out of an English naval base in the early sixties. One spy was a senior KGB controller who, in deliciously era-appropriate cover, posed as a Canadian vending-machine and jukebox salesman from Vancouver named Gordon Lonsdale. Two others, Peter and Helen Kroger (in reality Americans Morris and Lona Cohen), impersonated antiquarian book dealers – for some reason, also as Canadians – the métier providing easy cover for conveying coded messages in books. But the highlight here is Barnes’s description of the painstaking sleuthing that laid the groundwork for the group’s arrest, which included the tantalizing discovery of microdots (messages shrunk to the size of a period) in Helen’s purse, and adorable miniature maps and tools inside Lonsdale’s cigarette lighter.

Handout

In focusing on the still-unsolved 1962 plane-crash death of Swedish UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold, Ravi Somaiya’s The Golden Thread offers a more niche Cold War angle. While there are other books about the case (plus a recent documentary, the sensational but extremely mannered Cold Case Hammarskjold), Somaiya’s is exceptionally lucid in how it lays out its complex history and context, which involves colonial history and murderous Belgian corporate interests in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In voicing support for the decolonialization of Africa just as the continent was becoming a Cold War pawn due to its geography and natural resources, Hammarskjold ultimately found himself on the wrong side of multiple powerful interests, including the CIA. Particularly memorable is Somaiya’s empathetic portrait of Hammarskjold, who emerges as a Young Werther-type: a sensitive, melancholic loner who grew up in a pink medieval castle, wrote poetry, and suffered endless pricks of conscience.

Handout

Mid-20th-century Hollywood’s image as a hotbed for commies was mostly McCarthyist hysteria, an exception being the case of eccentric producer Boris Morros, which Jonathan Gill details in Hollywood Double Agent. Morros, a Saint Petersburg-born Jew who served as musical director in Tsar Nicholas II’s court (where he encountered Rasputin shortly before he was thrown into the Neva), came to America after fleeing revolutionary Russia, where he would eventually rise to become head of music for Paramount pictures and produce movies starring the likes of Laurel and Hardy and Fred Astaire. When Morros decided to help the Soviets place operatives in key company positions, however, he effectively became “Stalin’s man in Hollywood.” An unlikely spy, Morros’s motivation wasn’t ideology, of which he was devoid, but rather promises that his family would be protected back in the USSR. When those promises proved hollow, Morros flipped, becoming a double agent for the FBI. And when that status became public, Morros did what any producer with a strong appetite for self-promotion would do: he wrote a book and made a movie, casting Ernest Borgnine as himself.

Handout

Sticking with the Cold War arts front is Duncan White’s tome-sized yet fluidly written Cold Warriors, about the political role played by writers including George Orwell, Arthur Koestler, Graham Greene, Mary McCarthy, Vaclav Havel and John LeCarré from the pre-Cold War years through to the fall of the Soviet Union. We’re all familiar with the arms race, fewer of us with the “book race” through which the superpowers sought to flex their soft power. Indeed, Cold Warriors’ most fascinating parts look at how the Americans and Soviets weaponized writers and their work, sometimes without their knowledge – fiction and poetry having been seen by both sides as crucial to winning Cold War hearts and minds. In the 1970s, Moscow’s state publisher employed 30,000, while the CIA, which subsidized millions of books, pamphlets, and literary magazines through various fronts, went as far as air-dropping thousands of copies of Animal Farm onto Poland via balloon after the war. (Lightweight editions were produced for this purpose, killing innocent bystanders in a hailstorm of hardcovers being counterproductive to the agency’s aims.) The Eisenhower administration championed modernist and avant-garde literature for the sole reason that it was banned in the USSR. Writers being of a certain temperament, however, things occasionally got messy, as with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who proved a particularly loose cannon after he was deported from the Soviet Union. Prickly and uncooperative, he declared Western entertainments like rock and roll and the movies to be “manure.”

Literature, sadly, no longer seems to have a place in anyone’s political arsenal. The Democrats south of the border aren’t going to start carpet-bombing red states with copies of Bob Woodward’s Rage any time soon. Ensconced in our social-media-enabled ideological silos, most of us read to confirm what we know, not to open our minds, which makes it difficult to share the confidence of a wartime U.S. government memo that pronounced books “the most enduring propaganda of all.”