Handout

Toxic masculinity is, arguably, one of the biggest problems on the planet right now. In addition to propelling sexism, racism, terrorism, transphobia and the billionaire space race, it also fuels male depression and suicide. In 2019, the American Psychological Association declared “traditional masculinity ideology” a threat to the mental and physical health of boys and men. So what’s the best way to address this patriarchal plague?

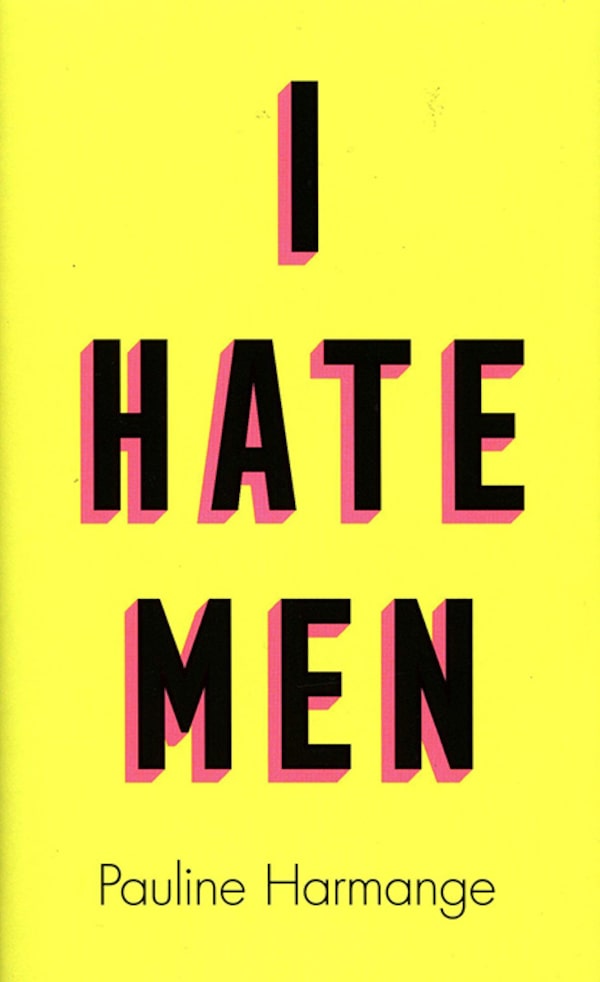

A new book by Pauline Harmange, I Hate Men, calls for women to get angry; Vivek Shraya’s I’m Afraid of Men seeks to educate men about the traumatic effects of their toxicity and the daily microaggressions perpetrated by those with male privilege; Liz Plank in For the Love of Men extends empathy for the ways that patriarchy and toxic masculinity are also bad for men. The idea of more love for the most privileged and violent group out there might rub some the wrong way, but compassion may prove necessary to truly transform masculinity.

I Hate Men was written after an online troll accused Harmange of man-hating. Originally written in French, Moi les hommes, je les détest, the polemic sold out after a government official threatened to ban the book for allegedly inciting hatred on the basis of sex. A manifesto by a blogger, the book embodies both the benefits and pitfalls of online discourse: a strong appeal to feelings, which galvanizes and divides readers. Harmange plays the provocateur by calling men “violent, selfish, lazy and cowardly,” and makes generalizations such as “men are trash,” even if she admits that her husband “is great and really supports my writing.” Her anger doesn’t just apply to violent abusers, but to all those “mediocre” men and “even the genuinely decent ones” whose privilege, she insists, make them hesitant to change.

The main advantage to Harmange’s approach to toxic masculinity is that it insists on a space for women to be unabashedly angry at the violence and injustice of patriarchy. If men get upset and refuse to help the feminist cause because their feelings are hurt, Harmange says, fine! “What if anger towards men is in fact a joyful and emancipating path when it is allowed to express itself?” This anger, she proposes, can lead to women-only communities and a sisterhood based on love of women.

Which is why Harmange’s approach to toxic masculinity seems useful for women, but perhaps not so much for men. “If our misandry alienates us from men who can’t cope with our anger, are they really worth our time?” I understand why women are angry, but as a guy myself, I also understand the backlash: it’s hard to feel hated. I may be breaking some code of masculinity in saying this, but I want to feel loved.

Vivek Shraya’s I’m Afraid of Men approaches masculinity from the perspective of its victims. The book illuminates the many aggressions and microaggressions experienced by Shraya, a trans woman of colour. As a child she had to learn to mimic masculinity; in high school she was bullied and spat on for being brown and queer. The first boy she liked threatened to beat her up for looking longingly at him. Once entering gay culture, she still experienced toxic masculinity that saw her as “too feminine.” Years later, coming out as trans, the harassment became worse as she was seen as “not feminine enough.” Shraya learned to wear clothes that wouldn’t bring attention to her, and avoided eye contact with men in the streets so that none of them would think she was attracted to them – which could have dangerous consequences. “None of these stories are exceptional,” she writes. “I’m afraid of how common, if not mild, my experiences are.”

Handout

Her sensitivity to microaggressions can help readers see the deep psychological effects that seemingly minor events can have on someone who’s been the target of toxic masculinity all her life. The book is suffused with the author’s pain and illuminates the condition of a deeply traumatized victim of toxic masculinity.

But there are limits to this approach; Shraya herself had concerns after conducting a decade of anti-homophobia and anti-transphobia workshops in Toronto, where “many of the participants were liberal.” Reflecting on the experience, she admits that she’s “afraid of the necessity of eliciting pity” in order to generate change. Pity is, in many ways, a form of privilege: Those who are relatively safe and comfortable in their cozy Victorian homes can easily afford to pity those who are … beneath them. The same strategy is going to face stark limitations when used on poor rural kids in Alberta, and will be useless against the boys and men radicalized by the internet to feel like they are the real victims of the current gender war.

At the end of the book Shraya calls for a blurring of all gender roles, and asks for trans people to be seen “as archetypes of realized potential.” While it’s true that trans and gender-fluid people provide models for a more creative relation to gender, it’s hard to imagine this approach appealing to people who aren’t liberally educated urbanites who already know and support diverse gender identities.

So is there a better strategy than invoking liberal pity? At the end of the book, Shraya speaks directly to the toxic man: “your fear is not only hurting me, it’s hurting you, limiting you from being everything you could be.” There’s a glimmer here of something potentially more powerful than pity: an appeal to freedom. What if we approached toxic masculinity not only as a form of violence against women and LGBTQ people, but also as an unhealthy limitation to the freedom of boys and men?

This is the direction explored by Liz Plank in For the Love of Men: From a Toxic to a More Mindful Masculinity. Plank is no apologist for men: Packed with research, the book is filled with hard stats and arguments showing how toxic masculinity harms women, people of colour and the LGBTQ community. But rather than rage against men, or appeal to pity, she demonstrates how toxic masculinity is also (if not equally) damaging to men.

A key example is male suicide. In the amazingly titled chapter “If Patriarchy is so great, why is it making you die?” Plank shows that one of the least-discussed victims of gun violence are gun-owners: the men who kill themselves. She cites studies showing that societies with more gender equality, such as Sweden and Austria, have lower rates of male suicide. Iceland, which has a high level of gender equality, also has very high life expectancy for men. When women are economically and politically empowered, Plank explains, men have support when if they fall ill or lose their job. What this means is that gender equality is not just a charitable concession to a less privileged group: it is healthier for and beneficial to both men and women. Plank’s examples work well to show how a feminist critique of toxic masculinity is good for everybody.

Unlike Harmange and Shraya, Plank doesn’t disavow the possibility of a “good man” who embodies positive aspects of masculinity. The chapter “Waffles are his love language” is a loving description of her father, and shows why Plank still believes it is possible to be a “good man”: the key is avoiding the toxic ideology of being a “real man.” The cure for toxic masculinity is what she calls “intentional masculinity.”

Rather than shaming men and boys about how toxic their masculinity is, Plank shows how men can thrive and flourish by defining a more mindful masculinity. Men who learn to be more attentive to their own emotional needs, she argues, will be more sensitive to and supportive of the needs of those around them. As a middle-aged man this makes a lot of sense: I was trained to think that emotional needs were a weakness to be ashamed of.

Handout

Plank sidesteps the antagonistic framework of a “gender war,” where one side’s loss is the other’s gain. Instead, she shows how both women and men will profit from a redefinition of masculinity. I’m a father to both a girl and boy. While it’s obvious how patriarchy threatens the freedom of my daughter, Plank also shows how it limits my son’s capacity for self-realization. So I want to see a transformation of toxic masculinity for the sake of both my kids.

Plank’s approach will appeal to a wider group of men because it is empathetic rather than moralistic: “I’m not trying to tell men who to be; I want them to become free to become who they truly are.” While some will, understandably, resist a call for more empathy for men, Plank points out why it may be necessary: “The most effective way to solve some of the world’s greatest suffering is to address male pain, because left unaddressed, it was turning into the greatest threat to this planet.” In a way, Plank is in a privileged position: one has to get past one’s own victimization and trauma to want to liberate the men who have been so toxic. But this compassion, and even love, may be necessary to eradicate the masculine threat to the planet.

Anger is a powerful force for jump-starting agency after being victimized or traumatized. And yet, in the divisive online climate of the day, we know that calls to “hate men” are bound to provoke more of the very toxicity they hope to eradicate. The appeal to liberal pity, while good for giving victims of toxic masculinity a voice, has a limited audience: it won’t necessarily convince a broad swathe of men to roll up their sleeves and transform their gender. Much more effective will be a call for redefining masculinity based on an understanding that the liberation of women is intimately intertwined with the liberation of men. It’s time to set aside the framework of a “gender war” and look for solutions where everyone wins. Men, women, trans, straight, gay and everything in between will profit from new definitions of masculinity that are more grounded in the emotional realities of being human. It’s time to liberate ourselves together.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.