handout

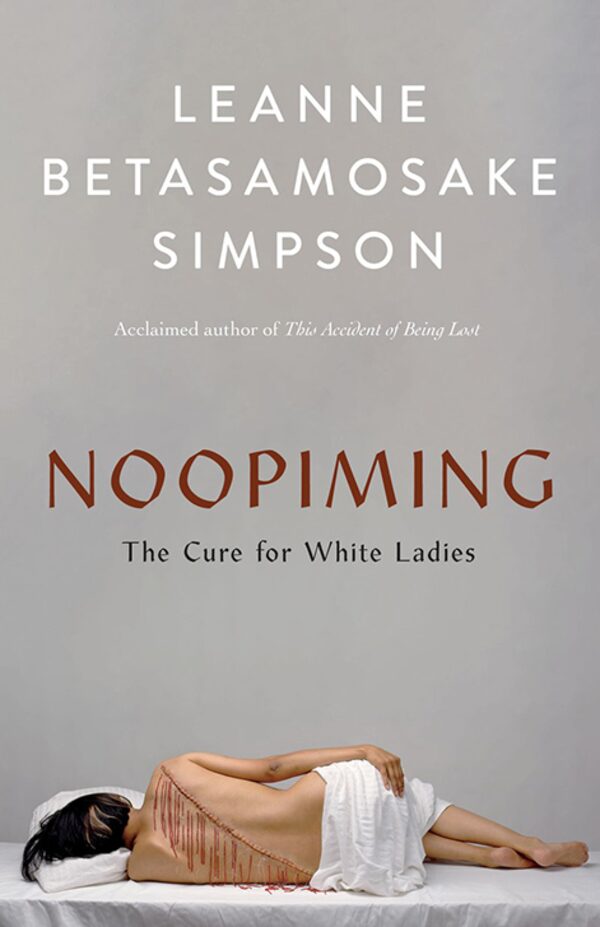

- Title: Noopiming: The Cure for White Ladies

- Author: Leanne Betasamosake Simpson

- Genre: Fiction

- Publisher: House Of Anansi Press

- Pages: 368

Noopiming: The Cure for White Ladies is a quietly startling new work from Leanne Betasamosake Simpson that, if you have read her previous works, reads as both familiar and completely new.

This brilliant novel is a carefully curated mix of prose and poetry, though the narrative and poetic form never leaves either; at all times, there is a deliberate attention to rhythm, movement, and sound. The layered storytelling is rich with wry and undeniable humour, and introduces readers to an incredible cast of characters, giving us the perspective of Elders, Indigenous youth, raccoons, geese, and trees, braiding together past, present, and future and intentionally centring Nishnaabe life and practices.

Though the book is structured into ten parts, the storytelling feels cyclical. It’s as if readers can begin anywhere in the book and it will feel like the beginning. Each of the sections is a world on its own, but each also speaks to the other sections, creating a webbed narrative that opens up worlds within worlds so carefully, like peeling back flower petals. Instead of following a linear timeline, we are following characters, getting to know them as intimately as if we were in the book too, as if we’ve shape-shifted into the very ink on the page.

If readers have read Simpson’s past works, some of these characters will be familiar. When I saw that Sabe, the giant who represents the narrator’s marrow, had returned, I felt as if I were seeing an old friend again. The other characters are written with such depth and complexity they feel familiar even if we haven’t met them before: from Mindimooyenh, the old woman who represents the narrator’s conscience, who loves a good bargain (or “bargoon,” as they say), and cares for each and every one of her kin with furious love; to Akiwenzii, the old man who represents the narrator’s will, who watches the Tour de France on his phone with Ninaatig, the maple tree, and complicates the notion that perfection comes with age; to Bougie Kwe who tries to bring “a little bit of real right into the city” by revamping their small backyard with “pumpkin seeds in ‘repurposed’ Styrofoam coffee cups. Trilliums in the garden. Fires in the backyard. Hyacinths in a plastic wading pool,” and fights with the resident esibanag (raccoons) who are just as much a part of the territory as they are.

As formidable as each of the characters are on their own, this novel celebrates and validates the collective, the relationships between one another, the animals, their ancestors, and the land. These relationships work as a formation, much like the formation of migrating geese in the novel, of which Mandaminaakoog says: “sure the formation is made up of individuals and individuals are formations in and of themselves. But that is the trick. To not get caught up in one’s own body, one’s own experience, one’s own cycling head. Synergy matters, because it represents the incomprehensible. The other forces and nations working with you even if you’re unaware.” It will ring true for many Indigenous readers that for these characters, the collective is survival, healing, and light.

The novel also acts as a reminder that Indigenous people’s relationship to ceremony is also an important aspect of collectivity. But like the tarps that re-emerge throughout the novel, bought at Canadian Tire for a bargoon and used by almost every character, ceremony is created wherever it’s needed and sometimes in forms you might not expect: it’s in an accidental run-in between Ninaatig and Sabe on the path between the city and the reserve, in Mindimooyenh’s annual trips to Ikea, in Sabe’s plastic water-bottle sculpture, in Bougie Kwe’s small backyard, and in Akiwenzii carving the chemical formula for polyethylene on the rocks at Kinomagewapkong. Their relationships to ceremony also act as a reminder that the land is everywhere, whether the characters are in a city or in the bush, and there is no one way to create ceremony or be in community – “what matters is showing up.”

Because of the ongoing violent effects of colonialism, all of the characters experience and have experienced dispossession of some kind. This dispossession is ever-present, and the novel acts as a portrait of what the world would look like for Indigenous peoples if these connections, to one another and to ceremony, remain collectively strong. This imagined future, thankfully, resists a utopian ideal; it’s instead a future that points to a past, one that “was never perfect, but it was always good enough.”

Noopiming felt in many ways like I was returning home, like I was drinking tea with my aunties and playing a hand of crib, settling into a night of laughter, truth, and story. As I’m a Nehiyaw person reading about people and homelands that are not my own, this is a wonderful feat. And my experience is different, I’m sure, to an Nishnaabe person or another Indigenous person, who would perhaps find meaning in other places. This is the beauty and masterful work of this novel: it holds something for every Indigenous person. It’s a gift that feels specifically for us.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.