Casey Plett.Sybil Lamb

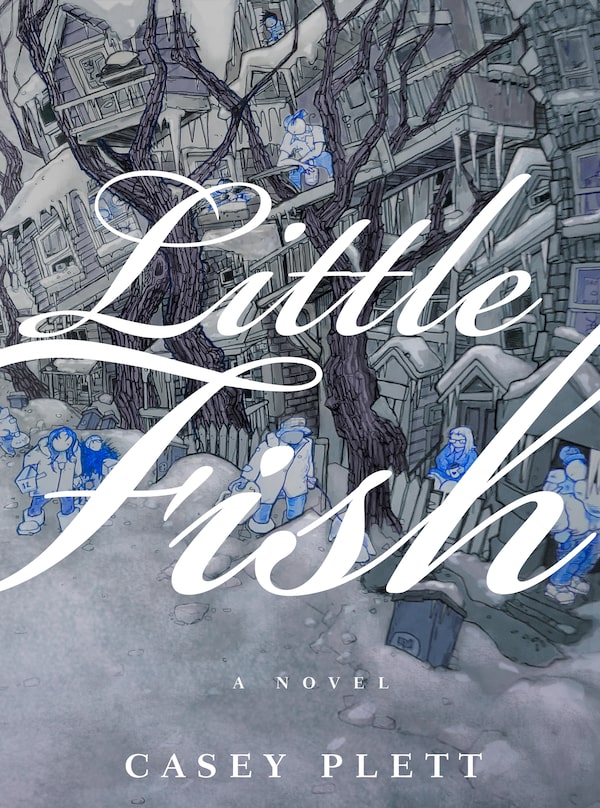

- Title: Little Fish

- Author: By Casey Plett

- Publisher: Arsenal Pulp Press

- Pages: 320 pages

Zero is not an empty number – it also marks an origin, the place you start from.

Casey Plett’s Little Fish does not have a prologue; instead, it has a chapter zero. Here is the place where this novel starts counting: four women talking in a bar, when one of them says, “Age is completely different for trans people. The way we talk about age is not how cis people talk about age.”

By “age” Sophie doesn’t mean lifespan or the years since starting hormone therapy or that hormones might make a person look younger – or not just those things. What she’s talking about are timelines. “Cis people have so many benchmarks for a good life that go by age.”

This is the set-up before we get to chapter one, before we properly meet Wendy Reimer, a 30-year-old trans woman, eight years post-transition, living in Winnipeg. Before Wendy’s grandmother dies and Wendy receives a strange phone call from a family friend suggesting Wendy’s devout Mennonite grandfather might have been trans. In another Canadian novel, this early revelation about a grandparent would become the book: Searching for Opa. But Little Fish is not that book. At either end of Plett’s debut novel is a search for queer elders. But before the first of those bookends, remember this conversation about trans age. This will matter, as Little Fish is ultimately not about the past but about the present – and looking forward to trans futures.

A friend recently told me that one of the things she appreciates about Plett’s work is how she so clearly writes for trans women. But the novel also deserves a wide audience. Every reader can get this part: being a trans woman is exhausting. Yes, even today, as attitudes change for the better, even in a city.

Those who read Plett’s first book, the story collection A Safe Girl to Love, will find similarities in Little Fish. Sophie, a recurring character in the stories, is a secondary character here. Sophie’s friendship with Wendy is fast but deep. No one gets Wendy quite like Sophie does: two trans girls from Mennonite families. The intersection between Mennonite culture and trans life is another tie to Plett’s previous work. But the part from A Safe Girl to Love I kept returning to when thinking about Little Fish was the refrain from the story “A Carried Ocean Breeze”:

“I’m tired of this.”

“I’m so very tired of this.”

“It exhausts me, it slows me down, it balls me up on the couch with movies and terrible food and it makes me weak. It’s not beautiful or brave or redemptive. It’s like a light case of mono that never goes away. I don’t want to be brave. I want us to be okay.”

I won’t catalogue the precarity of Wendy’s life, or the lives of her friends – this is what the novel is for – but I will note Wendy’s internal monologue at the novel’s nadir:

“More and more, I feel like life is something that’s just happening to me. My choices don’t feel like choices at all. It’s like they’re things that have been decided and I just react to them the way anybody would. The older I get, the more life feels like a blank, gauzy haze where every direction is just the same thing. It seems like other people have this way of pushing back against things in their life they don’t like, and I just don’t have that.”

Wendy is 30 years old, but she struggles to think of trans girls she knows who are older than her. This isn’t to present her life as a tragedy. (Indeed, Plett’s fiction actively resists presenting trans women’s lives as either tragic or inspirational.) A notable feature of this novel is that it is dialogue heavy, starting with that conversation in chapter zero. In a conversation, every new person multiplies the social interaction. By the same token, when a person leaves, it reduces the group by more than subtraction. Lila, Raina, Sophie – especially Sophie – Wendy’s dad, Ben: these are the people who hold Wendy up, the people whom she holds up, and we know that through the dialogue.

The older I get, my choices don’t feel like choices at all. I won’t spoil whether Wendy finds the queer elders she’s looking for. The reason she’s looking at all has to do with that initial conversation about timelines. For some people, aging is not an expectation but a privilege. Little Fish is not looking backward. It’s about Wendy making some choices so she can imagine herself at 60. Not about trans pasts, but trans futurity.

Jade Colbert is a regular Globe Books contributor.