Renata de Lélis appears in The Pink Cloud by Iuli Gerbase, an official selection of the World Cinema Dramatic Competition at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival.Courtesy of Sundance Institute

You didn’t need to attend the 2021 Sundance Film Festival to realize that the independent film industry is in deep trouble. But it certainly helped.

Across seven days, starting Jan. 28, the 37th edition of the festival that Robert Redford built – and which acts as the base of North America’s adult-oriented, non-blockbuster film ecosystem – unfolded in a manner both familiar and distressingly strange.

For starters: This was a virtual event. While there were satellite screenings in select U.S. theatres, most of the critics, filmmakers and decision-makers who typically shove themselves into Park City, Utah, every January were forced this year to watch, review, buy and sell films from the comfort of their couches/beds/bathrooms. There were even virtual “parties,” which produced one of the saddest images I’ve seen in my lifetime: a film critic’s stone-faced avatar sitting atop a wiggly digitized body, alone in an empty simulacrum of a Park City lounge.

Technically, the online shift made Sundance more accessible than ever. It certainly helped me, as I’ve never had the opportunity to fly down and expense a $5,000-a-week Airbnb that I would’ve had to share with seven of my closest film-critic frenemies. But even in its 2021 iteration, Sundance is something of an in-the-know, virtually roped-off event: Whatever films trickle out of its digital environs won’t be viewed by real-deal audiences for months, if ever. (Canadians were, as usual, left behind, geo-blocked from almost all of Sundance’s programming – though TIFF 2020 blocked viewers outside its borders, too, so it evens out.)

Ann Dowd and Reed Birne appear in Mass by Fran Kranz.The Riker Brothers/Courtesy of Sundance Institute

And about those films: Although it is wildly unfair to compare, look at what Sundance 2020, the unbeknownst last hurrah of the movie industry, offered just 12 months ago: Promising Young Woman, Palm Springs, The Nest, First Cow, Minari, Never Rarely Sometimes Always, The Assistant, Possessor, The 40-Year-Old Version, Kajillionaire, Relic. Basically, titles that would end up being the most acclaimed, Oscar-tipped of movies the year.

Of course, it helps when 95 per cent of competition abandons the release calendar. Still, last year’s Sundance proved to be an embarrassment of riches. This year? Mostly a straight-up embarrassment. And one that highlights the fault lines of pandemic-era Hollywood: filmmakers struggling to adjust to COVID-19 restrictions, desperate-for-content streamers spending money as if it was the end of the world (fair!), producers holding back promising titles for whenever a real theatrical market returns, and second- and third-rate productions getting passes from programmers because nothing else is available.

Of the 20 feature films I watched over the course of the festival (about 27 per cent of the total lineup), I felt like I was getting a glimpse of an even-more-depressing-than-now future.

Turns out, for instance, that making movies during a pandemic doesn’t equate to making good movies. The L.A.-set comedy How It Ends and the British folk-horror lark In the Earth were both conceived and shot in a coronavirus world. But neither film has anything new to say other than reminding us how much this moment truly sucks.

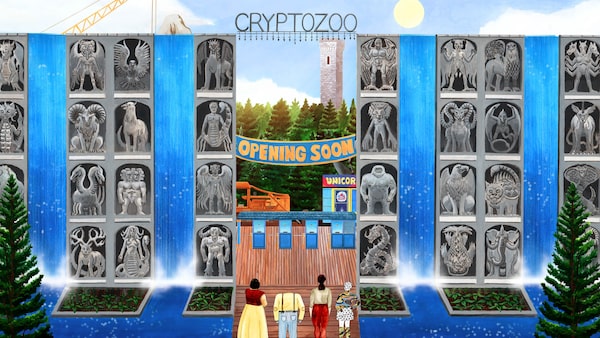

A still from Cryptozoo by Dash Shaw.Johnny Dell'Angelo/Courtesy of Sundance Institute

There was little relief, either, in the quirky-slash-eccentric-slash-unbearably-sad films that typically populate Sundance’s slate. The animated mumblecore experiment Cryptozoo, the suicide-pact buddy comedy On the Count of Three, the escaping-family-tragedy drama Land, the polyamory rom-com Ma Belle, My Beauty – all felt in need of another polish or three, and all underlined the likelihood that the festival was facing a dearth of submissions.

Christopher Abbott and Jerrod Carmichael appear in On the Count of Three by Jerrod Carmichael.Marshall Adams/Courtesy of Sundance Institute

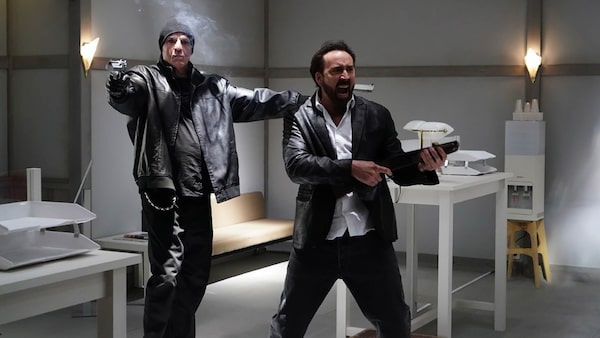

On social media – the only place to gauge reaction in a lobby-less world – colleagues swooned for the school-shooting drama Mass, the “explosive” COVID-19 documentary In the Same Breath, and the feel-good family drama CODA. But none lingered in my mind very long, or longer than it took to compose a snotty little tweet review. Even Prisoners of the Ghostland, a Sion Sono movie in which Nicolas Cage battles samurais and spirits in a post-apocalyptic Japan that seems explicitly designed for my brain, was too wan to lift my spirits.

Nick Cassavetes and Nicolas Cage appear in Prisoners of the Ghostland by Sion Sono.Courtesy of Sundance Institute

There were highlights, here and there. The Pink Cloud, an ultra-prescient dystopian drama from Brazil’s Iuli Gerbase, shook me deeply. Jane Schoenbrun’s screen-life horror experiment We’re All Going to the World’s Fair displayed tremendous confidence and visual wit. Questlove’s archival concert documentary Summer of Soul was a much-needed blast of artistic energy and political fury. Two Canadian holdovers from last fall’s TIFF, the revenge film Violation and the short Black Bodies, are admirable in their intensity. And I’m still wrestling with my feelings over Ninja Thyberg’s Pleasure, an assaultive look at L.A.’s porn industry.

Sofia Kappel appears in Pleasure by Ninja Thyberg.Courtesy of Sundance Institute

But a handful of delights can only float me so far. And I can’t imagine many of the titles, whenever they might be released, making a sizable dent in culture. (Okay, Summer of Soul could hit the mark.)

Perhaps the pandemic state of things has made me an incurable grump (or grumpier than usual). But the reception I was seeing for titles such as CODA – which was bought by Apple TV+ for a record US$25-million a few days before sweeping the festival’s awards – suggested that the industry is so desperate for good news that it is now grading on a curve, instead of responsibly flattening it.

Emilia Jones appears in CODA by Siân Heder.Seacia Pavao/Courtesy of Sundance Institute

There is a recurring joke in film circles that the reason so many critics go bananas for Sundance titles that evaporate outside Park City (The Report, Late Night, Me and Earl and the Dying Girl, Happy, Texas, etc.) is that the thin mountain air affects one’s judgment. But the fact that everyone was at sea level this year still didn’t stop the industry from getting high off a decidedly down-to-earth supply. Here’s to genuine peaks at Sundance 2022.

Plan your screen time with the weekly What to Watch newsletter. Sign up today.

Barry Hertz

Barry Hertz