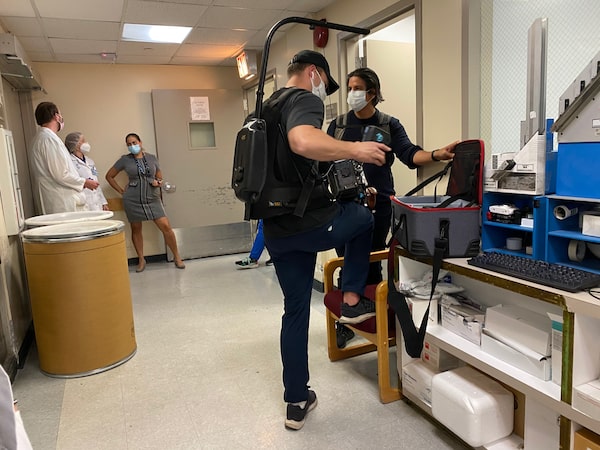

Janet Tobias and team from the Global Health Reporting Center in Vancouver at work on various reportage subject for Unseen Enemy.Handout

There are several billion-dollar races being run in the film industry at the moment. There is the race to open movie theatres. The race to restart production. The race to reconfigure the release calendar. The race to remake awards season. But there is another sprint that underlines all of these marathons, in a way: the race to make the first movie about COVID-19, while COVID-19 rages on.

A handful of experimental and anthology pandemic films have already been completed or are in the late stages of production: Russian filmmaker Timur Bekmambetov’s crowdsourced Tales from the Quarantine, Stacey Donen’s collection of Canadian shorts Greetings from Isolation and Vancouver director Mostafa Keshvari’s one-shot drama Corona. So far, though, industry eyes are awaiting a mainstream feature-length film chronicling the crisis, shot during the crisis.

The first mass-appeal, decently marketed and widely released movie to come out of the flames would signal not only that Hollywood is back in business, but serve as a reminder that film is an essential tool to our understanding of the world. Whoever gets to theatres (or wherever) first with a true coronavirus-focused movie will go down in history.

Of course, that chapter could be written a number of ways, not all of them favourable.

Late last month, news broke that Michael Bay, the critically reviled but prolific master of modern disaster cinema, would be the first Hollywood filmmaker out of this particular gate. His production company has teamed with Adam Goodman’s Invisible Narratives to shoot Songbird, a thriller from low-budget horror director Adam Mason that imagines our world two years in the future, with lockdowns increasing as the virus mutates. Filming is set to begin this month, with social-distancing measures in place.

While there is no release date yet set for the project – The Globe and Mail’s interview requests to producers were not returned – Songbird will likely be beaten to the screen by those working in a more nimble and perhaps more subject-appropriate filmmaking field: documentary.

A cursory tally of in-production COVID-19 docs runs to two dozen, with surely more in nascent stages. They include a look at shuttered restaurant culture from Laura Gabbart (Netflix’s Ugly Delicious), reportage on front-line health care workers by Janet Tobias (Unseen Enemy), a cinéma-vérité examination of life inside Wuhan by Yung Chang (Up the Yangtze), an investigation into how governments are using the pandemic as an excuse to flex their authoritarian muscles by Mila Turajlic (The Other Side of Everything) to a profile of celebrity chef Jose Andres’s humanitarian organization by Ron Howard.

Documentaries come equipped with a few distinct advantages over whatever feature-narrative COVID-19 movies might spring up over the next few months. Typically, documentaries require fewer crew members, fewer financial resources and don’t have to co-ordinate with the various film-industry guilds. And because docs are inherently designed to reflect the world as it is, they might not repel audiences as much as fictional, and perhaps crasser, takes on the crisis.

A cursory tally of in-production COVID-19 docs runs to two dozen, with surely more in nascent stages.

“Documentaries are more palatable right now, because what is the news every day but a documentary about the world? And people are watching a lot of news,” says Paul Dergarabedian, senior media analyst for box-office tracker Comscore. “But a dramatic retelling or a narrative film? That’s a whole different story. We just don’t know how people might react to that right now.”

One of the biggest names working to get his COVID-19 doc out into the world is Matthew Heineman, the Oscar-nominated director of Cartel Land. The filmmaker’s as-yet-untitled pandemic project, produced by the prolific doc guru Alex Gibney (Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room), is an on-the-ground look at public health care workers in New York, which he started shooting in March.

“When it became clear that this was going to affect our world in a major way, I felt like it was the most important story of our time, and I wanted to figure out how to tackle it immediately,” Heineman says. “I’ve made films about Mexican drug cartels to activists fighting ISIS and this is the hardest thing I’ve ever done. Most films, you can shoot and then go home and escape from it. This isn’t something you can escape from, both mentally and physically.”

Serbian filmmaker Turajlic echoed that desire to document the pandemic as it is unfolding – for the sake of history as much as cinema.

“There is that sense or urgency – to film what’s going on and get it out fast. But I began to think of this material as more a document for posterity. How are people five, 10, 15 years from now going to view this moment?” says Turajlic, who is working from her Paris apartment on a film about how Serbia’s government has used the coronavirus to blur the lines between protection and liberty. “That helped me figure out as a director who I’m addressing this to.”

As creators are racing to get their films out, though, there is the possibility of too many titles landing at once – especially as the all-important fall festival season approaches (however altered that might be this year).

“There’s definitely a sense of a race happening, but I think that it’s all about perspective and POV, too,” says the Toronto-based Chang, who is balancing his work on the Wuhan project with a short film about American medical workers co-directed with his life partner, Annie Katsura Rollins. “As an Asian filmmaker, I want to ensure that there are Chinese-driven stories getting out there, especially now because of the doublespeak and mistruths from world leaders. For the race itself, there’s a visible tension of trying to finish quickly, but for me it’s about making the best film possible. Better to make a strong film than a quick one.”

Overriding everything is the question of whether audiences – even documentary audiences, typically curious about the state of the world – will have the energy and enthusiasm required to sit down and watch a film about a reality almost everyone is exhausted and disgusted by.

“Timing is going to be everything. I think back to 9/11 and the films that came out around that, and while this isn’t quite the same comparison, there was a fatigue around the subject,” says Thom Powers, long-time documentary programmer for the Toronto International Film Festival. “Is COVID-19 going to be one of the stories that people are going to want to hear, or too much of a downer at a time when people are hungry for escapism?”

“I can’t really say what audiences want now per se,” Heineman adds. “I think people want information and clarity. But for me, I was trying to look into the future and ask what are people going to want to watch? I didn’t want to make a film about how we got here or what went wrong. I want to celebrate the amazing work of people out there fighting this, and to put a human face to the story.”

There is always the chance, as Turajlic says, that by the time these movies come out, “people might be oversaturated with looking at their screens. Maybe we’ll just want to go outside and look at trees for a few months.”

Plan your screen time with the weekly What to Watch newsletter. Sign up today.

Barry Hertz

Barry Hertz