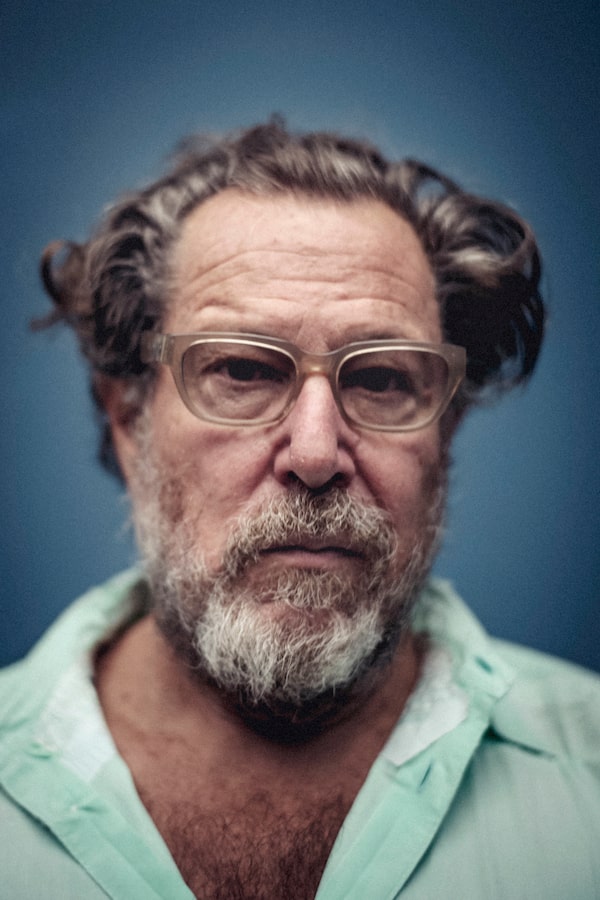

Julian Schnabel in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris on Sept. 28, 2018.JULIEN MIGNOT/The New York Times News Service

There is a tight little knot of meaning in the title At Eternity’s Gate, the name Julian Schnabel has given his new film about Vincent van Gogh. The title is taken from a van Gogh painting that shows a sorrowful old man bent forward in his chair; perhaps the film is just making a sad comparison: It depicts the artist, played by Willem Dafoe, during the last two years of life, the productive but troubled period that included his sojourn in Arles and in the asylum at St. Rémy.

Still, to an audience who has yet to see the film, surely the title invokes the irony of van Gogh’s massive posthumous fame: There he stands unknowingly, the artist who has never sold a painting, poised on the brink of immortal celebrity. Watch the film, however, and you’ll glimpse a different meaning of eternity: It is what van Gogh seeks, not egotistically but ecstatically, as he reaches for something transcendent that he sees in nature and attempts to paint.

It is that conflict between the public’s (self-congratulatory) image of van Gogh as the struggling artist whose work only subsequent generations will be smart enough to admire and the actual nature of the struggle that makes van Gogh a difficult subject for film, a character hard to retrieve from cultural hindsight.

“I thought everybody thinks they know everything about van Gogh: Why do it? But at the same time he’s the quintessential painter,” Schnabel, who is a painter in his own right, said in a recent interview. “I felt like I knew something about him that other directors did not know. … I thought I could demystify some of the ways of presenting him and show another way to feel him. I think the paintings speak, and in understanding how they are constructed and what he would have to do to make them, I thought I could show that to other people.”

The title of the film, At Eternity's Gate, is taken from a Vincent van Gogh painting that shows a sorrowful old man bent forward in his chair.JULIEN MIGNOT/The New York Times News Service

The image of the tortured visual artist battling a society not yet ready for his vision is comfortably installed in cinema, from Charlton Heston’s exhausted Michelangelo staring down Pope Julius II in The Agony and the Ecstasy to Ed Harris’ broken genius in Pollock and the portrait of Jean-Michel Basquiat as a fragile trickster in Schnabel’s own Basquiat. Of course, the leading example is probably Kirk Douglas’ overeager van Gogh in Lust for Life, the melodramatic 1956 bio pic that solidified the myth, severed ear and all. This time, Schnabel set himself the task of depicting the vision – and the suffering – from the inside rather than the out.

“[We did that] by shooting the movie in the first person, by making people feel they were van Gogh rather than making a movie about van Gogh, and by not sensationalizing things about him being a crazy person,” Schnabel said. “He is responding to whatever he has to do to get by every day whether it’s in this cold room where he turns his shoes into a painting, or [as] he walks through nature or people intervene in his reverie and he has to communicate with them. We wound up doing something very fundamental; it could have been about anybody.”

Schnabel deployed a variety of techniques to make the viewer see the world from van Gogh’s perspective. Cinematographer Benoît Delhomme uses a lot of shaky, hand-held camera movement to suggest the artist rushing into nature; extreme close-ups depict van Gogh’s lack of ease with others; a split diopter, a lens which brings both foreground and background into focus, allow us to see the artist and the landscape around him. Filming in and around Arles, they also shot improvised scenes with Dafoe when sunset’s “magic hour” hit, illuminating the Provençal landscape.

“There is a catalogue of different ways that tell the story so that it is not just a third party illustration of something about a historical figure. It’s as close to the way I would see something as I could make it, as a human, as guy running through the landscape, as somebody making a painting, as somebody looking at other people’s paintings. … It’s about an interior dialogue.”

Schnabel poses at a portrait session during the 14th Zurich Film Festival on Oct. 02, 2018 in Zurich, Switzerland.Andreas Rentz/Getty Images

On a more mundane level, films about painters have to depict the act of painting and they often rely on stunt actors to provide shots of hands at work. Instead, Schnabel taught Dafoe how to paint, coaching him how to look at his subject and mark his canvas. Meanwhile, if the art department wasn’t up to snuff, the director painted the props himself.

“I quality checked everything and when I had to paint a painting I did. There’s a self-portrait hanging on the wall in the asylum, I painted it. There’s a painting of Oscar Isaac as [Paul] Gauguin, I painted that. … Willem painted the shoes,” he adds, referring to an early scene where, closeted in a freezing room in windy Arles, van Gogh turns his worn-out shoes into art.

That is an act of both elevation and preservation, a way of freezing time as it marches toward death.

“We turn things into objects and we stop the world,” Schnabel says, quoting the Russian film director Andrei Tarkovsky on the subject of art and life. “Life contains death but art is … a denial of death. … It’s a way of preserving something, making a physical fact out of something.”

Schnabel disputes the standard wisdom that van Gogh killed himself after his removal to Auvers-sur-Oise, near Paris: The film sides obliquely with a story that suggests someone else was responsible for the gunshot wound in the artist’s stomach. He notes that van Gogh considered suicide an act of cowardice – and had just bought new paints. In a quest for eternity, van Gogh seemed to be on a roll.

“When he says “I am my paintings,” he is his paintings,” Schnabel said. “In that sense he speaks from beyond the grave, he transgresses death, and encourages others to do the same.”

So perhaps the figure of van Gogh can have it both ways, simultaneously achieving eternity through his famous person and through his transcendent art.

Kate Taylor

Kate Taylor