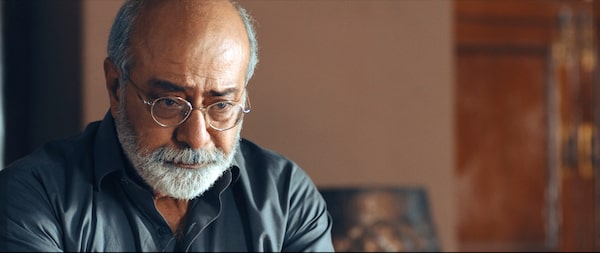

Asim Abbasi hopes his first feature film Cake will be a hit with women.Handout

Write what you know, they say. And so, like many artists before him, Asim Abbasi looked to his own family life for inspiration when he started writing his debut feature film, Cake. He’d been living in London for more than 20 years and was watching his parents in Pakistan age from a distance. Then, in a strange twist, his life started mirroring his script.

“In the film, the inciting incident is that the father gets ill and then the children start getting together. I had written the first draft – or half a draft – in February. In March my father had a heart attack, and we all got together,” says Abbasi, who came to Toronto earlier this week to launch Cake at a special event at Cineplex Courtney Park, along with the film’s two leading ladies, Sanam Saeed and Aamina Sheikh.

“We were having the same kind of conversations because my parents are quite old – ‘Should we get buried here, or buried there.’ These dark conversations on a very mundane level. There was a practicality, no drama attached. That intrigued me.”

Cake takes us into the layered lives of the Jamali family. Middle daughter Zareen (Sheikh) has been left to care for elderly parents Siraj (Mohammed Ahmed) and Habiba (Beo Raana Zafar, in a delightful turn as a feisty matriarch who wants to get more Instagram followers, among other scene-stealing moments), while older brother Zain (Faris Khalid) and younger sister Zara (Saeed) pursue their lives in New York and London, respectively. Zareen has to manage her parents’ day-to-day lives in Karachi, as well as the family’s extensive farmlands in Sindh, a southern province in Pakistan, having sacrificed her own ambitions to study baking at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris.

The parents’ ailments bring the children together in Karachi; the family then makes a trip to the old family farmhouse. Simmering tensions among the siblings re-emerge amid moments of nostalgia and humour. It all leads up to the reveal of a family secret, in a breathtaking 10-minute-long continuous shot.

In Cake, the Jamali family's father, Siraj (Mohammed Ahmed), gets ill, prompting the children to get together.handout photo

Cake is unlike the current crop of movies coming out of the Pakistani film industry (a relatively younger and smaller fraternity compared to its Indian cousin), which has recently been copying the big-budget brashness of Bollywood. It’s a quiet film, intimate in its storytelling with its close-ups, then zooming out for wide shots rich with texture and detail. It’s also somewhat unusual in the way it centres its lens on the two sisters Zareen and Zara, who form the emotional core of the film.

“I think I have a tendency to write more female characters because I feel I can play more with nuance. I come from a family with strong women so I’m sure it’s part of my subconscious,” says Abbasi, who worked as an investment banker in London for many years before studying film theory at the city’s SOAS University, and then studying at the London Film Academy. He didn’t make a conscious decision to write a female-centric film, but is all too aware of the idea of films being a mardana (male) medium versus TV being a zenana (female) medium in Pakistan.

“Because men leave the house to watch films, women stay at home and watch TV. I hope Cake changes that. Bol [2011] did that to a large extent – women flocked to the cinemas to watch that. But it was an anomaly. I hope Cake isn’t an anomaly.”

While the contemporary Pakistani film industry is still in its emerging stages, its TV industry has long been entertaining audiences. Saeed and Sheikh are celebrities in Pakistan and abroad, known for taking on characters on Pakistani TV dramas who challenge the status quo – to the extent that they can within the plot line.

Both wanted to be a part of Cake because they could relate to it. For Saeed, who grew up putting on small performances on a water tank turned stage in Karachi along with neighbourhood kids, Cake was an opportunity to play a role that was not far from her own life.

“I also come from a family of three siblings and two parents. We have the same relationship – the back-and-forths, the laughter, getting upset with each other,” she says. While she’s the eldest in her own family, and observed her youngest sister to figure out some traits of her character, she was surprised by how closely Zara reflected her own self. “In fact, there were two experiences that were happening in the film, which were happening in my own real life. So it was less acting, more being.”

Beo Raana Zafar is delightful as the feisty matriarch Habiba.handout photo

Nevertheless, the role required them to use some new acting muscles, says Sheikh. TV dramas don’t leave room for nuance, especially when you have to shoot 10 scenes in a day, and often not sequentially.

“We had to unlearn many things, we had to emote using triggers, go back in our own past to find those triggers. The subtleties of expression on film, where your smallest move can make a huge impact, it was all different,” she says. “And that one-take at the end, I’ve never had an experience like that before. Where everyone, the characters, the crew, lights going out and coming back on, everyone working like mad to achieve this thing together. We gained a lot as actors, and as film enthusiasts.”

For Abbasi, it was important to make a film that was on par with world cinema.

“Beautiful indie films are being made across the world all the time,” he says. “I want a non-South Asian to see it and not care that it’s a Pakistani film. Just that it’s a good film.”

Adds Saeed, “And it gives you great insight into how Pakistani women are, how our households are just like yours.”

Abbasi also hopes Cake leaves the audience thinking long after the credits roll.

“Maybe when you step out of the theatre, you feel like picking up the phone and calling your parents, or maybe your siblings,” he says.

Cake opens April 13 in Ontario, British Columbia and Alberta.