Todd Phillips's Joker recently won the most coveted prize at the Venice Film Festival.Courtesy of TIFF

Since the debut of the 1966 television series Batman, we’ve been introduced to the caped crusader’s most memorable villain, the Joker, 14 times. Of those, we’ve been subject to four big-screen Jokers, with three squeezed into the past 11 years alone.

After Jared Leto’s iteration in 2016′s Suicide Squad, you wouldn’t be wrong to think that we’ve collectively had enough Joker for another half-century. But 2019 is the year of going full Joker. With Joker’s North American premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival Monday night, just on the heels of winning the Golden Lion – the most coveted prize – at the Venice Film Festival, we get yet another version of the clown prince of crime. And finally, the Joker is the star of the show – not that he hasn’t always been the star, even when he’s inevitably beat by the world’s greatest detective.

TIFF 2019: Updated – The Globe’s latest ratings and reviews of movies screening at the festival

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that no villain in history has been as revered as the Joker, and in comparison to Batman, why wouldn’t he be? Batman is aspirational in the most unrealistic way possible. He’s a billionaire playboy whose origin story is, “My parents were killed before my eyes." The Joker, especially as director Todd Phillips portrays him in the new Joaquin Phoenix-starring film, is someone many North American men can probably relate to: The Joker has been kicked down by society for things beyond his control.

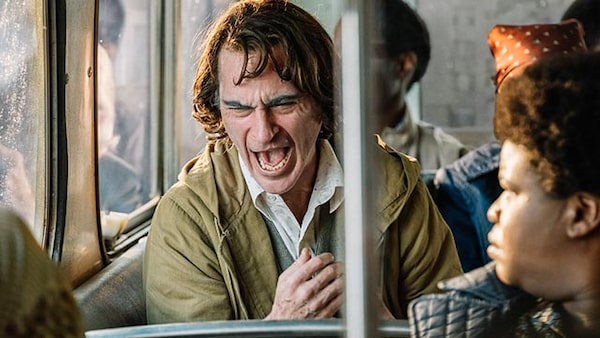

In Joker’s telling, Phillips focuses on a man named Arthur Fleck (Phoenix) and how he goes from a lonely and naive outcast to a master criminal who starts a movement. Initially, Fleck works as a clown, but yearns to become a comedian and win the attention of his hero, a late-night TV host (Robert De Niro, whose performance deliberately echoes the actor’s work in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy and Taxi Driver).

Throughout Phillips’s film, we see Arthur go through what we’re led to believe is just enough humiliation for him to become a murderous villain. Most incidents, however, are minor injustices magnified by a condition Arthur has, which causes him to laugh uncontrollably at random times (the audience laughed along at first, until noticing these episodes go on too long and seem painful). We see teenagers beat him up on the street, a mother ask him to stop playing with her young son and a co-worker manipulate him for little reason. Ultimately, Arthur doesn’t feel “seen” the way he wants to be, and yearns for more in his life. He carries around a book of stand-up material and predictably fails at an open-mic night because he begins laughing uncontrollably – and because he simply isn’t funny.

The film chronicles how a man named Arthur Fleck goes from lonely outcast to criminal mastermind.Courtesy of TIFF

For someone like me, a young woman who doesn’t read comic books but watches movies based on them with zero emotional investment or expectations, it is hard not to think about how a certain audience of men will perceive this version of the Joker. From Heath Ledger’s Oscar-winning performance in 2008’s The Dark Knight to Leto’s critically panned take, the Joker has always acted out the ultimate lonely man’s fantasy. He is a white man who has been dealt poor cards in life – be it a mysteriously scarred face, a toxic-waste accident or being forced to serve time in a mental institution – and therefore believes he has the right to do whatever he wants to better his own reality.

Phoenix’s Joker is no different, albeit richer in the sense that we get to see his origin story play out for a full two hours. Of course, villains aren’t expected to do the right thing, nor should they do the right thing – that’s why they’re villains, and that’s why we find them so compelling. Take how Thanos was depicted in Infinity War as needing to eliminate half of life in the universe to restore balance because of overpopulation and violence: A bad guy is more interesting when he’s kind of right.

Here, the Joker represents an ideology, becoming more vigilante than villain. He ends up creating a movement that helps the citizens of Gotham rise up against the 1 per cent who’ve neglected the city’s most vulnerable. But how exactly that ideology goes beyond a wan “society is bad and has been unfair to me” is hard to pin down. Whether intentional – and regardless of whether slices of the public will see Phoenix’s Joker as more hero than anti-hero – the film does offer a queasy sense of entitlement, which seems to ring true to how lonely, violent men view themselves.

This Joker wants more for his life, and only finds himself free when he begins killing those who’ve wronged him. We all know his mentality and motives don’t exist in a vacuum – we all see how sometimes lonely white men commit mass murder because they appear to feel misunderstood by society, or entitled to women’s attention, or because they want to cleanse society of whatever they deem a threat.

Some critics have been dancing around whether or not Joker is “potentially toxic,” but most believe, thanks to Phillips’s visual skills and Phoenix’s committed performance, that it might also be one of the best films of the year. I don’t disagree with any of that – but I do yawn at the idea of another story in which white men are offered a sort of understanding for their violence.

Joker hits close to home, but without caring whose home it exactly hits.

Joker screens at the Toronto International Film Festival Sept. 13, before opening across the country Oct. 4

Live your best. We have a daily Life & Arts newsletter, providing you with our latest stories on health, travel, food and culture. Sign up today.