Sara Hjellstrom had just had a tonsil operation when a friend, DJ-producer Mike Perry, handed her the roots of a song he hoped she could turn into a hit. Sitting on the couch in her Stockholm apartment, Hjellstrom built Perry's four chords into a tropical house track, with help from her songwriting partner Nirob Islam. The beat, top-line melody and the words came near-instantly.

Hjellstrom wanted her own voice on the track, but had been told by her doctors not to sing. Being from Sweden, though, where music is treated like a job – a profession, really, such as an engineer or electrician – she wanted to get that job done. So, a half an hour after she began writing, she stepped into her walk-in closet and recorded the vocals – in a single take.

In June, 2016, that song, The Ocean, began a six-week summer run atop Sweden's charts, reaching No. 11 on Billboard's American dance chart, too. Hjellstrom, who's taken on the alias SHY Martin, instantly went from music-school student to coveted co-writer and guest performer, jumping on tracks by the Chainsmokers, Kygo and Bebe Rexha.

The 24-year-old wants to become a household name, and she's in the right place to make it happen. Sweden is the low-key Nashville of the Nordics, a hit-making heavyweight that's one of the world's biggest exporters of music relative to the size of its economy. (The only country that has crept ahead of it is Canada – another country with a small population, a tendency toward hockey fanaticism and long, dark winters.)

Sweden has infiltrated global pop for decades. ABBA ruled the seventies; Robyn and the Cardigans tore a strip off the nineties; Tove Lo and Zara Larsson carry the country on charts today. Countless North American hits, too, are written by Swedes you've never heard of. The root causes of the disproportionate dominance of this country of 10 million, however, are less evident. One clue can be found in a single, vastly influential studio that began ushering in a new school of songwriting in the 1990s, sending teen-pop artists including the Backstreet Boys, NSYNC and Britney Spears flocking to Stockholm. Further clues can be found in Swedish culture itself, and the deep appreciation of music that's instilled in Swedes from an early age. "They're gods of pop music," says Carly Rae Jepsen, who regularly travels to Swedish studios, most recently for her forthcoming record.

Today, Sweden is responsible for much of the shape of popular music: how songs are written, how they're recorded and, now thanks to Spotify, how they explode into the world. "Just because you're a Swede," Hjellstrom says over coffee in downtown Stockholm, "people respect you right away."

In the 1990s, fresh-faced teen-pop artists including the Backstreet Boys, NSYNC and Britney Spears were flocking to Stockholm to record their next hits.

Ints Kalnins/REUTERS

At the centre of Kungsholmen, the island just west of Stockholm's core, there's a little two-storey storefront that changed pop history. Wedged between a highway tunnel, a playground and two impossibly drab mid-rise apartment blocks is the original Cheiron Studios.

The tan-brick bunker was, for nearly a decade, the finest hit factory in the world. It was founded in the early nineties by Denniz PoP, a remix pioneer with a gift for melody who propelled Swedish pop band Ace of Base to global fame, co-producing All That She Wants and The Sign. He cared little for the divide between the club and the radio, making music that bridged both worlds: beats you can't sit still for and melodies you can't forget. To road-test his prototypes, he'd blast them in empty discotheques in the dead of morning to assess their dance-floor effectiveness. The approach gave radio pop, long a critical castaway, an unforgettable immediacy.

Over time, Denniz PoP recruited a team of producers and songwriters including Jacob Schulze, Kristian Lundin and a metalhead who went by the name Max Martin. By the mid-nineties, fresh-faced teen-pop musicians started showing up in Stockholm to record with them, walking away with such classics as Quit Playing Games (with My Heart), Tearin' Up My Heart and … Baby One More Time.

When Schulze talks about Denniz PoP now, he almost always refers to his mentor as "he." His tone has the warmth of familiarity, but it's buffered by a deliberate, steely reverence. "He wanted to make songs for his cool friends, he wanted people in the countryside, everybody, to dance to these songs," Schulze tells me in late September in the lobby of his new studio. ABBA might be shorthand for Sweden, but with its new approach, the Cheiron collective became the architects of the late nineties teen-pop explosion, and in turn, much of pop ever since.

At Cheiron, Denniz PoP, and later Martin, sought the same thing from songwriting that today's tech execs do: simplicity and scale. A pop banger doesn't need to sound genius to be ingeniously constructed, but it's most effective, and financially lucrative, when it combines the elements that make it enjoyable across all demographics – the beat, the melody, the chorus almost scientifically calibrated to be unforgettable. Schulze, whose work with the studio included NSYNC's Bye Bye Bye, refers to Cheiron's guiding principles with a Roxette reference: "The really cliché concept of 'Don't bore us, get to the chorus.'"

Pop music was his kingdom, his magistrates eternally faithful. When he died in 1998 at the age of 35, after an unexpected stomach-cancer diagnosis, it shook the whole country. Days later, DJs all across Sweden held a moment of silence in his honour. His death rattled Cheiron even more – in mourning, Martin, Schulze and the gang took months to get back to work. When they did, they found the pop world had begun modelling itself in Denniz PoP's image.

The studio shut down a few years later, but the Cheiron diaspora are still making music today, and Martin, especially, commands immense control over pop. Much of Taylor Swift's new album Reputation is his production handiwork, and he has written or co-written more than 20 Billboard No.1-hits, including Swift's Shake it Off, Katy Perry's I Kissed A Girl and the Weeknd's Can't Feel My Face.

There have been whole academic papers dedicated to figuring out why Swedes so disproportionately rule popular music. There are less-than-scientific theories – it's dark so much of the year, so let's go inside and be creative! – and many more reasonable ones. Those include a national tendency to be earlier adopters; role models such as Martin and ABBA, and the globalized audiences they captivated; and a profound national proficiency in English, the unofficial language of pop.

Patrik Berger, a 38-year-old who has spent his entire life messing around with sound, has other ideas. His studio is in a little house, not much bigger than a shack, in a hidden courtyard off a main drag on the Stockholm island of Sodermalm. There, he brings me over to a Korg Mono/Poly synthesizer along the red-velvet wall of the back room, and starts fiddling with a knob: It was this synth, in this room, that helped him shape the iconic, throbbing bass backbone to Robyn's Grammy-nominated 2010 single Dancing On My Own. The song put him in the spotlight as an in-demand songwriter and producer. "It was one of those songs where people came up to me, talking about how much it mattered," he says.

Berger, whose catalogue includes Icona Pop and Charli XCX's

I Love It and numerous other Charli songs including Boom Clap, believes Sweden dominates pop in large part because music is woven into life at an early age, and at minimal cost, through education. It's why artists such as him and Hjellstrom take it as seriously as any other job. Younger students are entitled to at least 230 hours of music education and can steer hundreds more into electives such as lessons, music-theory study and ensemble playing.

In high school, students can choose music as their primary stream and have many different classes to choose from. Nearly a third of Swedish children, meanwhile, get publicly subsidized music education after school hours, and adult education associations offer space, equipment and workshops, one study says, while grants are available for bands to cover rehearsal costs.

"It was just part of life: Kids should learn how to swim, kids should learn how to play an instrument," Berger says. "If you can't afford a saxophone, you just rent it – for basically nothing. What can be more encouraging than that?"

Hjellstrom began playing guitar before she was 10, started taking after-school music classes and was in a band at the age of 12. In gymnasium – Swedish high school – half her class time was spent studying and practising music. By 17, she says, she was signed to the label EMI on the strength of a YouTube video. Later, at a songwriting academy in Northern Sweden, Hjellstrom spent a year writing at a private studio, taking notes from publishers and labels, honing her craft, before moving to Stockholm for a year of internships. She hadn't even graduated when she finished The Ocean.

"We can afford to make mistakes and experiment," she tells me. "You can afford to find yourself, and your own expression, without having any pressure, money-wise."

Max Martin has said he feels the same way. "I have public music education to thank for everything," he told an interviewer in 2001.

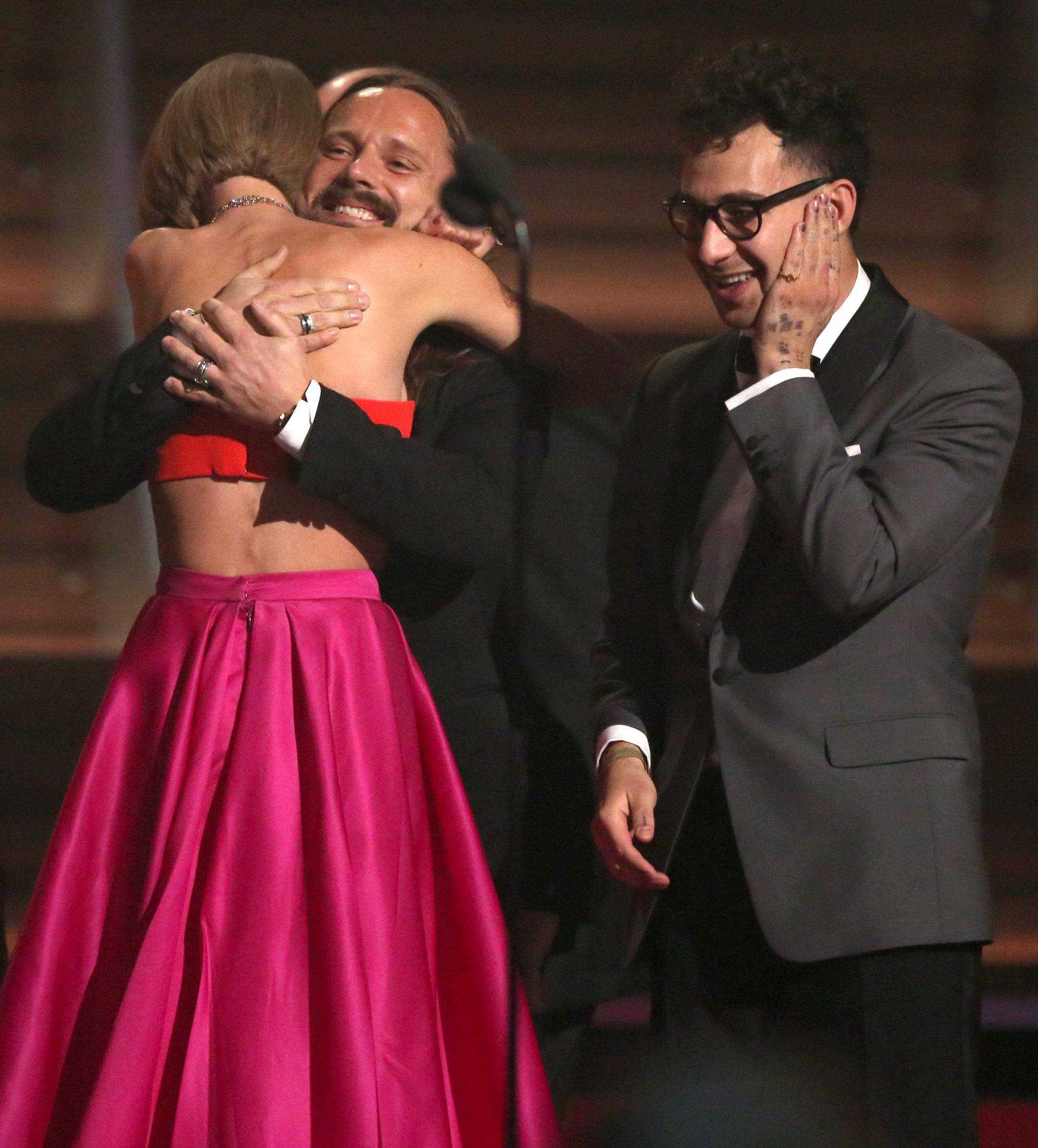

Producer Max Martin speaks at the Grammy Awards on Feb. 8, 2015.

Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images

By the time Hjellstrom first picked up the guitar, the boy-band wave had already crested, but Martin and his colleagues, taking Denniz PoP's mantle, had infiltrated all of pop music with their methodical approach to songwriting and production. When journalist John Seabrook wrote a book about this movement, he called it The Song Machine: within a few years of Cheiron's demise, music, the industry, had become industrialized. Martin's once-proprietary pop process is now global gospel: Producers take beats and chord progressions, offer them up to a series of "top-line" songwriters such as Hjellstrom to gift it with melody and hits are made.

This system has helped Hjellstrom get into songwriting sessions she couldn't have dreamed of. Berger, too, says this has been undeniably helpful: "When all this success with Max Martin happened – you see him going and getting milk at the store – everybody felt, 'If he can do it, then I can do it as well.'"

Today, the songwriting and production community there has grown well beyond the Cheiron disapora. Carly Rae Jepsen, for example, has worked not just with Martin associates such as Shellback and Rami Yacoub, but others such as Berger, too. "They just get really good at their craft," she told me in September.

But some sonic scholars, Berger included, have come to believe that Martin's school of pop is getting old: It makes songs that sound wonderful, but feel inherently repetitive.

Sweden's future will be brightest, Berger says, if the kids aren't afraid of getting a little weird. When he writes, he says, he's aiming for a "window" of song that captures commercial appeal without destroying music's mysteries. "That little window is so tiny, you have to throw a lot of balls to see one thing cut through that little crack – to actually change something."

He talks about the pressure he faced working on Dancing On My Own. "When I did that song, so many people were telling me what I should do with it," he says. Rather than follow the pack, he wrote it how he wanted to, inadvertently establishing his voice as a producer and songwriter. "They were so angry that I produced it in the way that I did. Why? No, it should be like this – it should be raw and gritty."

Hjellstrom's looking to try new things, too – starting with a debut solo single. As much as she looks up to Martin, she's also smitten by Tove Lo, a younger pop star held in equally high regard for her songwriting and her solo work – two worlds Hjellstrom is also hoping to occupy. "As a songwriter, you can hide behind the artist," she says. "You don't have to be in the spotlight if you don't want to. And I love that. But it will be really exciting to release my own stuff as well."

Sweden has never had a perfect scene. In November, more than 2,000 women in its music community signed a letter accusing the industry of enabling sexual assault and harassment, sexism and a culture of silence around it all. Hjellstrom signed the letter.

"I didn't hesitate for one second before signing," she says. "This affects all of us regardless of sex. Reading the stories from these women, not only do I recognize myself in them but I'm also angered by the fact that I meet these perpetrators on an almost daily basis."

The foundations of Swedish music are shifting in many ways. Artists and genres have diversified, and a significant DJ culture has emerged, with Avicii, Axwell & Ingrosso and many others carrying on the work that encouraged Denniz PoP to get into music. The country might now be better known among casual music fans as the home of Spotify, the world's most popular subscription streaming service. And despite all the milk he purportedly buys from Stockholm convenience stores, the press-shy Martin, and some of his former colleagues, spend much of their time in the United States.

Record producer Max Martin and musician Andrew Taggart in Sherman Oaks, Calif., on Sept. 28, 2017.

Alberto E. Rodriguez/Getty Images

When Martin and Spotify chief executive Daniel Ek launched the Equalizer project this year to promote women's work in the music industry, Hjellstrom was one of the first songwriters on board. She's quickly finding her way to the forefront of Sweden's changing musical identity. Earlier this year, too, she and her writing partner won the grand prize at the Denniz PoP Awards – a series of music prizes founded in 2013 by Jacob Schulze.

"We felt that he shouldn't be forgotten," Schulze says. He and his old Cheiron colleagues agreed the finest tribute to Denniz PoP would be to champion newcomers; the awards' tag line is "The Legacy Continues."

"That's much more important work, and much more important to me, than giving away prizes to established artists," he says. In championing new, homegrown talent, the awards are a distinctly forward-looking celebration of Swedish history.

"I didn't even think I would end up here," says Hjellstrom, who grew up in a tiny village a few hours from Stockholm. "I'm really enjoying doing what I love, and doing it with friends." But she's travelled the world for work – for music – more this past year than the rest of her life before it, often to even bigger music hubs. Sometimes, she says, she feels pressured to move.

That's another thing Sweden has in common with Canada. The Weeknd, Drake, Justin Bieber, Carly Rae Jepsen, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young: Each of these music juggernauts spends some or all of their time in the United States. SOCAN, Canada's performing-rights society for songwriters, has nearly 900 members in California alone. Music's globalization has given artists from small-market countries such as Canada and Sweden disproportionate, although welcome, influence in pop music. It can also pull talent away from home.

"It's kind of a natural step," says Berger, who spends some winter months in California himself. "I mean, what are we gonna do here? It's 10 million people; there's only so much you can do." But maybe this isn't a bad thing. Swede-made music can now reach more ears than ever. So, too, can music made by Canadians. And there's a pipeline of inspiration and encouragement, too, coming back to both countries. "They bring back new ideas, and it just becomes this big loop," Berger says.

It's the kind of thing that helps new artists such as Hjellstrom get their start. "As soon as you get role models like Drake and Justin Bieber," she says, "the younger generation will start doing music."

In November, a few weeks after we spoke, Hjellstrom released Good Together, her debut solo single as SHY Martin. In less than a week, it was streamed more than a million times.