After the third and final performance of Les Misérables, Lakeshore Collegiate Institute’s acting students cry their makeup off backstage – and then head with drama teacher Greg Danakas to a local church basement for the cast party.

There, the 30-odd students involved in the production eat pizza, drink pop and take group selfies on the dance floor before moving into a smaller room for the main event: the speeches.

This is a long-standing Lakeshore drama ritual. Each student who will not be in the spring play next year – whether due to graduation or for any other reason – gets to give a farewell speech. It’s a big deal: Bradley Plesa, for instance, the graduating student who played Jean Valjean, was up until 3 a.m. the night before writing his speech.

Jesse Thompson, who played the young revolutionary Marius, goes first and sets the tone in a valedictory address. He teases each of his cast mates, then praises them – moving from the youngest up to drama executive president Hilliary Lyn, his close friend and frequent co-star, who played Cosette.

“We’ve taken 10 bows together in 10 different shows,” Jesse T. says, “and now it’s time to take the bow for our childhood.”

It turns out the earlier weeping at the school was just a warm-up. Boxes of tissue are slid back and forth between groups of crying teens gathered in clumps on the floor – and piles of used ones begin to accumulate in all corners. It is an astonishing sight to an outsider – the only comparison I can draw is to the scenes of mass mourning after Princess Diana died.

And Jesse T.’s 20-minute speech is just the first of the evening. At around 1:30 a.m., with no end to the tributes or tears in sight, I leave the students and their bleary-eyed chaperones to this ritual – and say goodbye for what I think will be the last time.

STORIES THEY TELL

Following Lakeshore’s production of Les Misérables through four months of rehearsals, I learned a number of lessons about the roots of the problems that ail professional theatre in Canada today. But what is it that the students learned from putting on this play? Why is drama on a high school curriculum anyway – rather than simply being an extracurricular activity?

Lakeshore’s website lists the following “life skills” that drama students will develop in the introductory class: “self-esteem, confidence, public speaking, group skills, negotiation and leadership.”

These sound a lot like business skills – and, indeed, Jim Ellis, the management consultant (and stepdad) who played the narrator Victor Hugo in Les Mis, gave a lecture to Mr. D’s cast one day about how the students’ theatrical expertise might transfer to the corporate world. Allan Easton, Lakeshore’s principal, argues for the inclusion of theatre in his school’s curriculum in a not dissimilar way. “There’s certainly a dramatic push right now for STEM [science, technology, engineering and math] – a huge push, not just in the board, but in society,” he told me. “I would still argue, as an educator, that having the ability to speak in front of a group of people … whether you’re the accountant making the pitch, or in any situation, that’s a huge skill.”

I understand the desire to distill the importance of drama class down to marketable skills, just as I understand why theatre companies argue for grants and donations by touting the economic spinoffs their work generates. It’s just that this language always misses the point – it’s like describing the importance of a certain medicine by listing its side effects. No one buys a ticket to a play because theatre helps the restaurants in the area do well, just as no one studies acting imagining how they’ll perform in a boardroom.

I think there’s more to it, anyway. In ancient Greece, theatre and democracy were born one after the other – and some scholars believe the former helped give birth to the latter. The Greeks didn’t come up with ritual or storytelling, but they did invent dialogue – and Duke University’s Peter Burian has argued audiences learning to listen to characters present different points of view in the theatre paved the way to them listening to each other in democratic discourse.

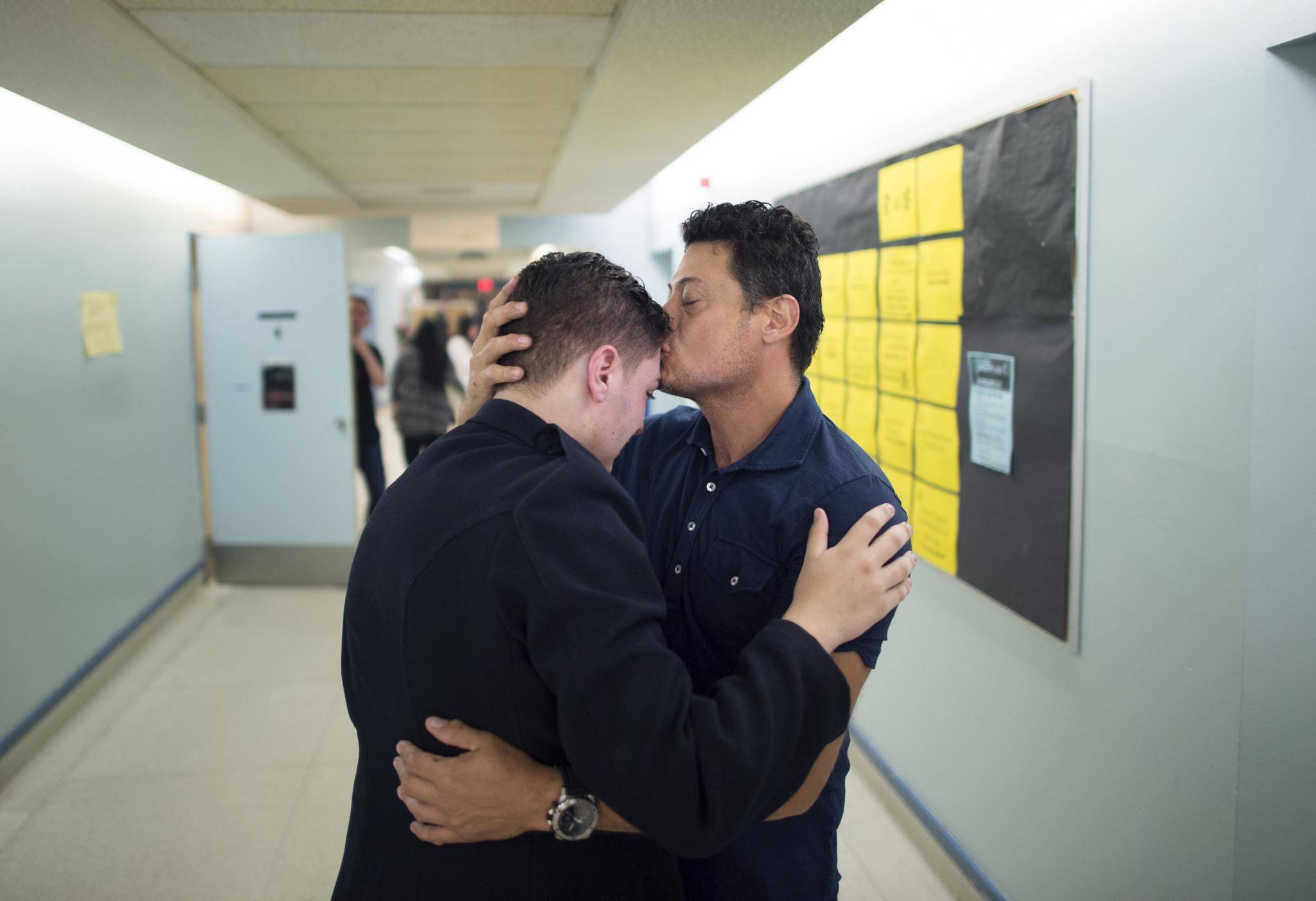

Learning to act requires you to go even further and put yourself in someone else’s shoes. It breeds empathy, and the empathetic are good citizens. I could see how empathy grew in Mr. D’s students through their cast-party speeches. Most of the praise to fellow students was delivered in this way: I didn’t like you at first, but now I understand you and like you.

Mr. Danakas, the proud Greek who sees his students as a family as well as a class, puts it simply when talking about what he does. “I always say drama is the most important class in the school. It’s about teaching kids to be human beings,” he tells me. “I’m going to sound like a tree-hugger: It’s all about love – it’s about loving the kids, loving the play, loving each other.”

Gallery: See more photographs from the stage and behind the scenes.

THERE’S JUST ONE MORE THING …

Is that what Mr. D’s students feel they have learned from acting and lighting and costuming Les Misérables? On the last day of classes before exams at Lakeshore, I pay a final visit to the Toronto school’s drama studio because I had forgotten to ask them this question.

The atmosphere is oddly tense as I enter the room – it couldn’t be further from the group hugs and the tears of the cast party. It’s the only time I’ve seen any teen in Mr. D’s class look like they were waiting for the bell to ring.

With little left to do in acting class now that the play is over and the assignments have been handed in, Mr. Danakas essentially hands the reins over to me – and I take off my shoes and sit down in the circle to asks these teens what they have taken away from working on a non-musical adaptation of a novel published in 1862.

Many of them did talk of love – it seemed almost everyone related to Eponine, who pines for Marius, who is in love with Cosette. “I guess life’s like that: You don’t always get what you want,” was the lesson Jaime Wells, who played Eponine beautifully, learned, confessing her own unrequited crushes. “You’re not always going to have a happy ending.”

Jesse McCormack, the eager-beaver stage manager, has a different perspective on Les Mis, having been in and out of the foster-care system since he was five years old. Jesse M., who is on a victory lap at Lakeshore, describes his first set of foster parents as “brutal people” – not unlike the Thénardiers who take in Fantine’s young daughter, Cosette, simply for the money. But it’s not Cosette who Jesse M. relates to as he reflects on the play – it’s Jean Valjean, who must go through life with the stigma of having been a prisoner.

“Jean Valjean became Monsieur le Maire: He escaped that past, though it came back to haunt him,” Jesse M. says. “I was in foster care – and there’s always that image in the back of my mind, of what a foster kid looks like.” He pauses. “I could smell like the prison. I could stink like the prison. Or I could overcome it.”

This is the best monologue I’ve heard all semester – delivered by the stage manager. And with that, I ask Mr. D’s class if they have any questions for me in return about the series I’m planning to write.

“Where do you buy a newspaper?” Bradley asks.

A MICROCOSM

No one in Lakeshore’s acting class asked me for a speech – or to tell them what I had learned from Mr. Danakas’s class. If they did now, this is what I would say:

I came to Lakeshore with a naive point of view. I really did want to renew my faith in theatre after becoming frustrated with professional theatre in this country – and rediscover the joy of theatre I had felt as a high school student myself. But you only get to be a teenager once. And what I found when I looked at high school drama through an adult critic’s eyes were things I hadn’t noticed the first time around. I found an acting class that wasn’t fully representative of the racial diversity of its school, and that it was easier for students from certain economic classes to participate than it was for others.

I found a high school theatre with less money and less audience than it used to have, and more hoops to jump through, set up by administrators and unions. I found bureaucracy and I found self-censorship – and I found art’s value being sold with the language of business.

But what I ultimately discovered at Lakeshore is that the dissatisfaction that I’ve been feeling about the professional Canadian theatre I cover as a critic isn’t really about theatre at all, but about the wider society that theatre exists in and reflects. If theatre and democracy have indeed been linked since ancient Greece, then it makes sense that theatre would suffer from the same problems as our democracy – which is also unfair and bureaucratic and filled with leaders who speak to taxpayers instead of citizens.

In the end, what will always make live theatre special and frustrating is that it involves actual people up on stage performing for actual people in the audience. It is a microcosm of our society. It’s too much to expect utopia from an art form made out of us. Unlike with film or television or Netflix, however, the dialogue is not distant. At a play, we’re all in a room together, audience and artists, riddling out all our problems. And maybe if we get closer to doing that in a theatre, we can get closer to doing it in society.

SO LONG, FAREWELL

Goodbyes are difficult – not everyone gets a poetic exit line like Fantine, like Eponine, like Valjean. When the bell rings, Mr. D’s students don’t linger – and the drama studio quickly empties. All that’s left for the summer are Lakeshore students from the past, frozen in production photos on the wall under a sign that reads: FAMILY.

The reason Lakeshore’s final acting class was so tense, I learn now, is that Bradley and Mr. D had a fight before I arrived. A tired Bradley, who was recently elected prom king, felt the final class was pointless; Mr. D criticized him for his lack of leadership in that moment. The argument escalated and the two went, in Mr. D’s words, “head to head.” That was the last time Mr. D and Bradley spoke after four years of working together as teacher and student – and as I write this in August, they still haven’t made up.

This ending makes a certain type of sense: Big, boisterous Bradley Plesa is more like big, boisterous Mr. D than any of the other students. He’s even headed to York to study acting this fall, as the first in his family to go to university – following on the exact same journey Mr. D embarked on a little more than three decades ago. That kind of intense connection between individuals is hard to end with a wave or a hug – and, since Mr. D casts himself as the Greek father of his students, it’s not surprising that matters took a dramatic turn.

On this day in June, the last day of classes, Mr. D doesn’t seem bothered by this as he closes the door to his office (a sticker on it reads: “Hugs, not drugs”). He is already thinking about what play to do next, and about the Grade 11s who will become Grade 12s next year. “I’ve never had a class of kids like this, Kelly,” Mr. Danakas says to me. “I’ve never had a class of such perfect students.”

Gallery: See more photographs from the stage and behind the scenes.