Actors don't get weekends. Instead, theatre companies tend to have one day a week when no performances are scheduled, traditionally called the "dark day."

At the Shaw Festival, the eclectic repertory theatre company now in its 56th season in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont., Monday is dark day – and it was on just such a Monday this summer that something dark took a popular, outgoing 22-year-old actor named Jonah McIntosh.

The previous day, Sunday, July 9, Jonah and his partner, Marcus Tuttle, social-media manager at the Shaw, had taken advantage of rare, overlapping time off to go on a hike around the Niagara Escarpment. Then, they saw the new Spider-Man movie – which Jonah, a Marvel fan, pronounced his favourite version to date – had dinner and drove home listening to songs from the Broadway musical Hamilton, singing and dancing along in their seats.

After dropping Jonah off at home, Mr. Tuttle exchanged goodnight texts with him – and that was the last anyone would ever hear from the young performer.

It was only on Tuesday, the day after dark day, that anyone grew seriously concerned about unanswered texts to Jonah's phone. Members of the Shaw ensemble started trying to contact the actor after he uncharacteristically missed a rehearsal that afternoon. Then, he didn't show up for the call for his evening performance of the musical on the main stage at the festival: Me and My Girl.

Later that evening, Mr. Tuttle was home with his family when his boss reached him to tell him that his partner had been found. "She had to tell me three times what had happened, because I didn't believe her. I didn't want it to be true."

The disappearing act

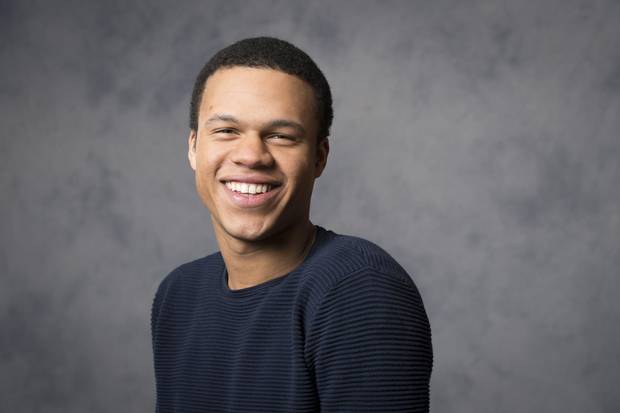

Jonah McIntosh in a park in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont., home of the Shaw Festival, earlier this year.

Family handout

Theatre is, in a way, all about disappearance – it's an ephemeral art form that vanishes in front of your eyes. That makes the theatre critic a kind of a eulogist, trying to find words to describe something that will never be again.

I didn't realize how literally that would be the case, however, when I began covering the theatre for The Globe and Mail almost a decade ago now.

There are a tremendous number of people who have made a mark in theatre, in this country and elsewhere – and, like everybody else, they die after long careers, or short ones, and often too soon. I've become accustomed to snapping into action, working on obituaries or tributes when an actor passes on, and it has become, like anything, a routine of sorts.

But Jonah McIntosh's death this summer was entirely different than any I had encountered before. For one, it came right in the middle of the Shaw season; the two shows the actor was performing in had opened a little more than a month previously and were scheduled to run well into the fall.

And then there was the guarded release from the Festival – followed by a outpouring of grief marked by disquiet on social media that eventually made it apparent that he had taken his own life.

"Nobody can remember this happening, ever," Tim Jennings, the executive director at the Shaw Festival, told me later.

The shock of the suicide was intensified by people's perception of who Jonah was, a musical-theatre performer who had made friends not just with fellow artists in Niagara-on-the-Lake, but the box office workers, ushers and even the staff at the gym where the actors worked out – a "bobby dazzler," in the words of artistic director Tim Carroll, "who was always smiling and making everyone around him smile." His Instagram account featured video clips of him singing hymns and show tunes at his piano and photos of sunrises and sunsets. "I'm living in a painting," he posted alongside one shot where you could glimpse the Toronto skyline in the distance across Lake Ontario.

My first impulse was to not write about Jonah at all – it seemed impossible to do full justice to who he was as a person, and also write about his death and its impact. I feared that one story would overwhelm the other. It's tempting, natural even, to want to search for answers or a clear single story in a situation such as this, but that would be a futile mission – one of the defining qualities of Jonah's death was the extent to which it seemed inexplicable.

But that something can be two things at once is the core lesson of theatre – an actor and a character are both there on a stage, and it's only the person at the centre of it who can really say where one ends and the other begins. It's only a critic who would be foolish enough to think that he can pull a mystery such as that apart.

'He had that something special'

By the time Jonah McIntosh finished his studies at Sheridan College in the spring of 2016 he was at the top of his cohort.

David Cooper

First and foremost then, let's remember Jonah McIntosh in life. It's not an exaggeration to say that he was a star in the making – and his path to the Shaw Festival was an exceptional one. Jonah, who grew up just east of Toronto in Courtice and Ajax, had impressive raw talent as a singer, dancer and actor when he applied to Sheridan College's competitive Music Theatre Performance program in his final year of high school.

But the son of two police officers didn't have the years of private training of many who get accepted right away, and ended up on the waiting list – and, though his father, Dan McIntosh, feared he was due for a disappointment, Jonah waited and waited with uncanny confidence all through the spring and to the very end of the summer.

He received his acceptance just two days before orientation in the fall of 2012. His mother, Lisa Daugharty, scrambled to help him pack and find him a place to live near the school in Oakville, Ont., at the last minute.

By the time Jonah finished his studies in the spring of 2016, however, he was at the top of his cohort. He landed a series of professional gigs, right way. By August, he was at Neptune Theatre in Halifax performing in Beauty and the Beast – and so when it came time to audition for the Shaw Festival for the first season under Mr. Carroll, he had to do so over the Internet.

Ashlie Corcoran, director of the musical

Me and Me Girl at the Shaw this summer and incoming artistic director at the Arts Club in Vancouver, told me about the day she and Mr. Carroll watched Jonah's callback. "He completely exploded out of that Skype screen into the room with us – so spirited and joyful," recalls Ms. Corcoran, who went on to give him a number of small roles in the thirties musical, featuring his dancing in its show-stopping number, The Lambeth Walk. "We all knew we wanted him as part of the company – he had that something special that's going to make someone a star in the future."

Indeed, Jonah was in the enviable position of getting more offers than he could accept. He had, for instance, lined up a role in Joseph and the Technicolour Dreamcoat for the coming holidays – but then turned it down after he was cast in a bigger show, the commercial Christmas pantomime at the Elgin Theatre in Toronto.

At the Shaw Festival, Jonah was not just in Me and My Girl but also Rick Salutin's 1837: The Farmers' Revolt – the first time he had acted in a play rather than musical. Off stage, he joined the cricket team, was part of the Shaw gospel choir and showed up regularly to classes that Mr. Carroll has been running for the company. There were already plans in place to bring him back for the 2018 season.

"Jonah was everybody's friend," says Travis Seetoo, a company member who was in the same shows (or "on the same track," in repertory theatre jargon) as Jonah in this season and had grown close to him, recording music with him in their spare time. "He was the heart, soul and life of the party."

The importance of ensemble

Jonah McIntosh (centre) with the cast of 1837: The Farmer’s Revolt.

David Cooper

Mr. Carroll was about to turn off his cell and walk into a play in Toronto on July 11 when he got word of Jonah's death. He made the call to cancel that night's performance of

Me and My Girl, then got in his car and drove the 2 1/2 hours back along the shore of Lake Ontario to deal with the crisis. "It's just a play," he said to me, when I sat down to interview him in Niagara-on-the-Lake a few weeks later.

The small, colonial-era town floats in the middle of a sea of fruit farms and wineries, and the close-knit community of artists who work there at the Shaw Festival make up a sizable portion of the population. The Ontario repertory company operates out of four theatres and employs more than 60 actors each season, almost year-round – and about 600 employees in total at in the summer tourist months.

There's no protocol for what to do in a situation such as this – but Shaw's leadership did its best to manage news that was traumatic for themselves as well. At the 15-minute call for Me and My Girl, the show's stage manager called the cast, orchestra and crew out of their dressing rooms and into the green room of the Festival Theatre where Shaw's planning director Jeff Cummings delivered the news. "I can't really describe the devastation, loss, sadness and shock that rippled through the room," Mr. Seetoo says in an e-mail. "We all stayed in the green room for a long time crying and consoling each other, taking turns supporting and being supported."

Shows at the Shaw Festival in other theatres around town were allowed to go on, their cast and crews as yet unknowing – but director Meg Roe shut down the dress rehearsal of the Will Eno play Middletown, which was taking place in a building attached to the Festival Theatre. The newly renamed Jackie Maxwell Studio Theatre was transformed into an in-the-round gathering area with coffee and tissue boxes.

As curtain calls took place elsewhere around the bucolic tourist town, either Mr. Carroll or executive director Mr. Jennings tried to let the rest of the community learn the news face to face. About 80 per cent of the staff was told in person – and a phone tree filled in the gaps as best it could before Mr. Carroll sent out an e-mail, one of many he has since sent to the company.

"The one thing that one has learned over similar events in one's life – not that there's anything quite comparable – is that you can't communicate too much," says Mr. Carroll, whose best friend took his life 12 years ago. Presence, he felt, was the most important thing – in grief, as it is in theatre.

From the Studio Theatre, actor Marci T. House invited everyone over to her house – and the Shaw family filled it, overflowing onto her porch and front lawn. Her neighbours, newlywed actors Kristi Frank and Jeff Irving, lit a bonfire in their backyard, and anyone who wanted to sit in silence simply watching the flames did so late into the night.

By the next day, professional grief councillors were on site at the Shaw Festival, as they would be for weeks to come – but the company continued to look out for each other as well. A few actors took it on themselves to fill the green-room fridges with precooked meals to make sure everyone was eating, while a pair of Indigenous cast members led a smudging of the theatres Jonah had been performing in, attended by the full company.

Only after Mr. Carroll had consulted with the ensemble – the word does, after all, come from French for "together" – did they decide to start the process of getting the shows Jonah had been a part of back on stage.

Me and My Girl went first, just a day later – with David Ball, the associate choreographer, stepping into his featured roles for the short term until another actor could be hired.

Modifications nevertheless had to be made: A standout number early in the show called Thinking Of No One But Me, where Mr. Ball, Mr. Seetoo and Jonah had originally tossed the actress Élodie Gillett around while she sang, had to be rechoreographed for two men and one woman. "I found it very difficult to do it because Jonah's presence was so keenly absent," Mr. Seetoo writes.

Since officially taking over the Shaw Festival this season, Mr. Carroll has made it a more casual, friendlier place – and, as part of that, he's introduced a new ritual in which an actor or a stagehand or a front-of-house staff member gets up on stage before each show to say hello to the audience. The day after Jonah's death, the artistic director took on that role himself, explaining to the Me and My Girl audience that the musical comedy was missing one of its youngest performers.

"It's certainly the toughest performance I've ever gone through," recalls Ric Reid, a veteran actor with the Shaw Festival who acted alongside Jonah in both Me and My Girl and 1837 and had grown close to him. "It's really something to see a cast of 23 people struggling so hard and yet putting out a show that is so entertaining that it makes people laugh under those conditions."

1837: The Farmers' Revolt, a more intimate show with just eight actors playing multiple roles, was even harder to resume. The drama about the Upper Canada Rebellion was created, in 1973, with input from the original cast. In the Shaw Festival revival, the actors were equally involved in shaping it. "Jonah's creative fingerprints are all over the piece," Mr. Seetoo says.

Director Philip Akin came back to town to rework the ending, where two of the rebels are executed – the staging of the deaths were now too disturbing to enact. "You have to do your first performance without him. You have to do your dance routine without him," Mr. Reid told me, when I talked with him a few weeks afterward. "Even this week, we're still going through firsts."

I can't imagine actively feeling an absence on stage next to you day in, day out through to October – but Reid tells me performing can be therapeutic. "The late [actress] Joyce Campion used to say: 'When tragedy hits, you need Dr. Theatre,'" Mr. Reid says. "It's a way of paying tribute and focusing and putting your energy in a good spot."

No clear answers

Jonah McIntosh, at three years old, with his baby brother, Cody, at home in Ajax, Ont., in early 1998.

Family handout

I went to visit Jonah's parents at his father's house in Ajax a month minus a day after their son's darkest day to learn more about him.

Daniel McIntosh and Lisa Daugharty, police officers both, separated when Jonah was 5, but maintained joint custody and remain close. Often, Dan and Lisa would go to church together on Sunday with Jonah and his younger brother, Cody; Michelle, Dan's wife and Jonah's stepmother; and a grandparent from one side or the other. "For people at church, we were the Modern Family," Dan says.

When I arrived, there were pictures of Jonah lined up on the kitchen table around a bamboo box containing his ashes decorated with music notes and a guitar. More photos covered every inch of a folding card table: Infant Jonah, captioned "August 16, 1994, 7 lbs, 6oz"; Jonah as a little boy, holding baby Cody; the brothers as boys leaping over rocks together. Nearby: a picture of Jonah dancing joyously with his grandmother, who in retirement has become an instructor and has taught everything from belly dance to ballroom, and another of Jonah, shirtless with suspenders, that reminded his father of Leroy Johnson in Fame.

From the later years of his life, Jonah's parents have computer folders full of digital photos – as well as audio and video files scattered between hard drives, Instagram and Facebook. Theatre may be ephemeral – but young theatre performers now document so much of themselves online that traces linger.

Lisa has found some solace in these moving images ever since she learned of her son's death, but Dan was only beginning to be able to find pleasure in his son's voice and movements again when I met with him; at first, he had to go out for air when someone would press play.

Lisa showed me many of her favourite videos – a beautiful tune Jonah wrote about the melancholy of the Christmas holidays; a gorgeous performance by the slender, six-foot-one baritone of John Legend's All of Me from his third year at Sheridan College in front a full band and back-up dancers; an Instagram of him singing How Great Is Our God not long before he died – which Dan, a Christian, finds particular comfort in.

As we watched, Dan – who also describes himself as a "sports guy" – told me about Jonah's all-around athleticism as a boy, his sweet swing in the baseball diamond. It eventually became clear, however, that his son's main interests laid outside sports. He recalled once standing in a line of dads at a football practice as Jonah did pliés and pirouettes on the sidelines in full uniform.

"I realized after, if he's courageous enough to do that at 14, 15 years of age in front of a group of middle-aged men," Dan says, "he knew where he was going."

At the same time, Jonah's parents tell me that their son resisted being defined by others growing up. He would say he was both black (like his father) and white (like his mother) – and when he came out to his mother as a teenager, he didn't want to be put in a box. "You know, Mom, I just want to be able to like whoever I want," is how he put it.

There were incidents of bullying owing to his skin colour and sexuality. Dan once dropped Jonah off at a bus stop, and a boy made him cry by asking him if his father was a robber. In high school, boys he'd been playing football with for years called him a homophobic epithet and complained that they didn't want him in the locker room. In his young adulthood, he also had to deal with comments in that vein from time to time, mainly online – during a long-distance job interview, or on his Facebook page.

Jonah McIntosh (right) takes a selfie with his younger brother, Cody, at the gym in Ajax, Ont., this past December.

Family handout

But Lisa has the screenshots of her son's smart, sensitive responses to the ignorance he occasionally encountered on the Internet – and is proud of his commitment to social justice. She also showed me a Facebook post from Jonah's 22nd birthday: "Happiness is a choice. It's taken me my whole life to be happy with who I am. I know it's always going to be a process, but now at 22, for the first time, I'm not afraid to say I'm proud of my ethnicity, my sexuality, my body, my dreams, things I foolishly was ashamed of."

So, when a group of colleagues from Lisa's division showed up at the door of her home in Courtice on 10:20 p.m. on July 11, while she quickly knew it was a death notification – "We've done the notifications. We know what it looks like" – she would never have guessed the cause of death. "Never in a million years," she says.

Jonah's parents wish, of course, there were clear answers. His mother wonders if some blame can be placed on the demands of his chosen career, the steady adrenalin leading up to opening nights followed by a withdrawal. (The Shaw Festival has a number of wellness programs already in place for its artists – but Mr. Jennings tells me they're working on making them more pro-active and crafting better mentorship programs for young company members.) His father notes, meanwhile, that his son had episodes of what he would call anxiety since he was a boy. Jonah also experienced a trauma when he was around 16 years old – one that he talked about only with his closest friends and his mother, who helped him get counselling. Later, in his second year at Sheridan College, he had flashbacks and his family helped him get professional help again.

He was private about this, and Lisa wants to continue to respect that. I can understand – it's impossible to know its relevance to the suicide. Jonah left no note, no explanation, and of late, he told his mother only how happy he was in Niagara-on-the-Lake – in a job he said felt like a vacation, in an artistic community that he loved and with a romantic partner he thought might be "the one."

"I was heartbroken because Jonah used to tell me everything, almost too much; every time he needed something, he would call me," she says. "I held out hope that maybe he put a letter in the mail. And nothing came."

'Mystery is a part of life'

Jonah McIntosh (second from right) in Me and My Girl.

David Cooper

The day before he died, Jonah and his partner, Mr. Tuttle, visited Brock's Monument, a column that rises above Queenston Heights on the escarpment. Jonah posted a photo of it to Instagram. There's something beautiful in the unremarkable caption that was his final message to the world: "Statue right here is larger than it appears."

Writing about Jonah's death threatens to define him by just one dark day, rather than the life he lived before something inside him overtook him.

In his obituary, Jonah's family thanked Mr. Tuttle for making "Jonah's last day on earth so very special" – but, when I talked to Mr. Tuttle, he wanted to emphasize that what made that day so very special for him was how ordinary it was, how much smaller it was than it may appear now. "We just had dinner – it wasn't like a magical candlelit dinner, it was just dinner," he says.

A moment in time can be both ordinary and deeply significant at the same time; even the most tiniest, most common human interaction can also be mysterious and unsettling and tragic. To me, no recent play has managed to depict the way life can be both banal and baffling – how just slightly out of the reach of understanding its joys and its tragedies can be – like Will Eno's Middletown.

I saw Meg Roe's gorgeous production of this American play set in a small town during my last trip up to the Shaw Festival in the Studio Theatre at the end of July – and, even without knowing the role that physical space had played earlier that month, it turned me completely upside-down. I wept as I haven't in years.

The cruel comedy of Benedict Campbell's police officer holding a baton to the neck of a local addict and demanding: "Be filled with humility. With wonder and awe. Awe!" The beauty of the theatre filling with tiny LED stars as Karl Ang's astronaut whirled around on a rolling chair and spoke of rocks and words and breath as being "sacredly and profoundly and mysteriously – yeah, well – earthly." The embarrassed yet grateful look on Gray Powell's face when he runs into a friend at the hospital after attempting suicide. The deep sadness in Moya O'Connell in the scene after her character gave birth as she listened to classical music on the radio with her baby and a nurse came in and silently filled her water glass.

I had seen Me and My Girl director Ms. Corcoran after the curtain call, looking stunned, and, when I talked to her about Jonah, we talked about Middletown as well. "For me, that play was a big part of grieving," Ms. Corcoran said to me. "There are some things that you can't unpack – mystery is a part of life."

Sheridan College and Jonah's family have set up The Jonah McIntosh Memorial Scholarship fund, a fundraising campaign launched on Aug. 16, on what would have been his 23rd birthday – it can be found at gofundme.com/jonahmcintoshmemorialscholarship.