Liberal Party Leader Justin Trudeau claimed in his first campaign speech on Aug. 15 that the current election “maybe the most important since 1945 and certainly in our lifetimes.”DAVE CHAN/AFP/Getty Images

Pardon me, if you will, for assuming any commonality between us, but don’t you find that right about now, halfway into a “snap” late-summer election, is when details start to matter? The frothy opening practice weeks of the campaign (with 40 per cent of the country and probably all of Quebec not yet paying any attention) have presented the usual freak show of absurdities, from paltry disinformation campaigns (the Liberals attacking Conservative Leader Erin O’Toole on health care) to bathetic attempts to appear humane and caring (Mr. O’Toole taking a principled stand against puppy mills), all set against a bewildering but easily photographed background (in this case, anti-vax protesters who turned up wherever Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau did). As nice as it is to be outside again, doing something communal, the entire juvenile merdescape irritates everyone.

But then Labour Day arrives. The chill of fall is instantly discernible. In Canada, this means it’s time to get serious.

Suddenly you begin to notice specifics. For me, this time, it was a stray statistic: that the federal government spent $322-billion to fight COVID in 2020 alone. What with extended CERB payments and wage subsidies and child-care plans and emergency health transfers, the pandemic alone could leave us with a debt of half a trillion dollars that will take at least a decade to pay off.

In other words, thanks to COVID, Big Government is back in a way it hasn’t been since Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher tried to dismantle the nanny state in the 1980s. What does that mean for post-COVID Canada? Do we want the government to be our partner? Our parent? Both? Is that a good idea? How will we pay for it? And do we have any choice?

Federal government posts $12.7-billion deficit for June as spending drops

COVID has stripped away our fondest political illusions. Beset by crisis and competing for everything from vaccines to hospital gowns, the free-trading, co-operative global marketplace – the Washington-based consensus model of geopolitics – disintegrated into what looked like a particularly nasty episode of Survivor. “The world is a different place,” Robert Asselin, a vice-president of policy at the Business Council of Canada and a senior fellow at the Munk School of Global Affairs, told me the other day. “Countries are moving to assert their national interests.” The ever-expanding emergency of climate change has made Canada’s oil and gas reserves infinitely less desirable to the world. Meanwhile, U.S. President Joe Biden’s new protectionist twitches have rendered the American market, Canada’s long-time security blanket, a lot less certain.

In two weeks, we’ll elect the people who will have to deal with all this (and climate change to boot). Their decisions will dictate our quality of life – what we can and can’t afford – for decades. A century ago, in the 1920s, Argentina and Canada were similar-sized resource-based economies, ranked equal in terms of global economic potential. Canada consciously moved beyond its ties to Britain and hitched its wagon to the American economy, thereby becoming one of the richest countries on the planet. Argentina had no such strategy, and has been an economic basket case ever since. This may have been a snap election, but it is also, as Justin Trudeau rightly claimed in his first campaign speech on Aug. 15, “maybe the most important since 1945 and certainly in our lifetimes.”

So here’s the next question: Why hasn’t he mentioned it non-stop since? And why do his opponents keep insisting this is a fake and unnecessary election? We need to make some huge decisions fast.

Transformative crises have shocked the world half a dozen times in living memory – you know the list – but make no mistake: COVID was a calamity of gargantuan proportions. Franklin Roosevelt and the U.S. Congress spent $788-billion (in today’s dollars) to climb out of the decade-long Great Depression. The U.S. has spent $4.2-trillion on COVID relief in a year and a half. That’s $12,390 a person, versus $6,311 a person over the course of the New Deal.

The more harrowing a crisis is, the more instructive it can be. The Depression inspired the creation of unemployment insurance, though not before the Privy Council declared it unconstitutional in 1937, which meant the program wasn’t enacted as law until 1940. By that time, everyone was hard at work preparing for war, which is what actually pulled Canada out of the Depression. Daniel Béland, the director of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada, maintains that COVID in turn revealed the stinginess of unemployment insurance, hence the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, or CERB. Collapse and response are the double helix of crisis capitalism.

“When we have these shocks, these major crises, they open up these critical junctures,” Prof. Béland says. “We can say that COVID as a crisis is a critical juncture for radical change.” The trick is to use the juncture wisely.

In 1944, as the Second World War ended, Canadians were gloomily petrified another depression would descend upon the land. Lagging in the polls, Mackenzie King’s Liberals introduced the family allowance, or baby bonus ($5 to $8 a month for every child under 18). It was a genius move, borrowed from Britain. The ensuing baby boom helped build houses, suburbs, the auto industry and a postwar optimism that – under the minority Liberal governments of Lester Pearson elected in 1963 and 1965 – went on to create universal health care, the Canada Pension Plan and student loans, all bulwarks of Canada’s famous social safety net. We even got a new flag.

Social and economic disasters, in other words, reveal our weaknesses, but they can also breed almost organic solutions. The financial collapse of 2008 led to Obamacare in the United States (despite partisan opposition) and to a modest expansion of the Canada Pension Plan here. (The Conservatives opposed the move until newly elected Justin Trudeau enacted the changes in 2015.) At this very moment, Mr. Biden is using COVID to justify huge infrastructure spending and an even huger anti-poverty/climate change program. “What’s going on in the United States is the outcome of 40 years of Reaganomics,” a senior backroom Liberal opined over the telephone the other day. “They don’t have a social safety net. They only just got health care, kind of.”

Our own freshest flower of COVID is the “$10 a day” national child care/early education program announced by Chrystia Freeland this spring. The advantages of early-childhood education are well established, and last for generations. The idea has been kicked around in Liberal circles since Paul Martin’s day in the 1990s. But it took COVID, and the disappearance of women from the work force during the pandemic when schools were closed, to make it a $9-billion annual reality. Jerry Dias, president of Unifor, the country’s largest private-sector union, considers the initiative a perfect example of the good things that can come out of a crisis. “We’re not going to have a booming economy unless we get women back to work,” he insisted when I called him. “We can’t go back to pre-COVID economics. Look what happened: We realized we couldn’t take care of ourselves in a crisis. We’d outsourced our own safety. We didn’t even have masks or protective equipment or the vaccines we used to manufacture here in Canada. It showed us how unprepared we were related to our social problems. So I’m not afraid of overspending now. That’s the type of broader discussion we need to have in this country.”

I found it bracing, even moving, to speak to a business leader such as Mr. Dias, who openly put the welfare of humans ahead of the bottom line. After decades of decline, union coverage reached a 15-year high during the pandemic. For all its oppressiveness and tragic death, the pandemic also freed us, at least momentarily, from the sanctimonious obligato of capitalism, with its steady nag that everything has a price we probably can’t afford. Justin Trudeau intuited that longing, hence his breezy public confidence and short TV campaign ads that end with him saying “That’s what I’m gonna do” – a disobedient tone well suited to our pent-up zeitgeist. Having spent a year and a half indoors trying to figure out how not to die, people are keen to indulge their dreams a little.

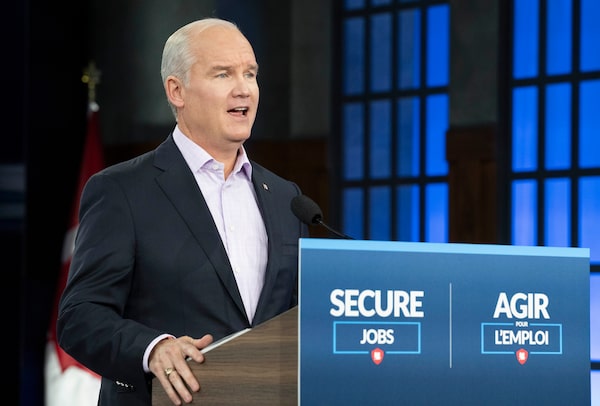

During the campaign, Conservative leader Erin O'Toole has attempted to sidestep the party's reputation as reluctant spenders.Frank Gunn/The Canadian Press

Which doesn’t mean they are affordable. Economic crises are more challenging for Conservatives, given their (not always deserved) reputation as reluctant spenders and fervent bookkeepers. Mr. O’Toole is attempting to sidestep that stodgy rep by being more liberal than the Liberals, the same way Mr. Trudeau won in 2015 by moving to the left of New Democrat Thomas Mulcair. Like the Liberals, the Conservatives have promised to invest in everything from child care to the innovation economy, without providing two specks of real detail as to how they’ll pay for it. But some larger trends are obvious. On the day Mr. Trudeau was claiming the election was the most important in a lifetime, Mr. O’Toole was quoted as saying “we can’t afford more of the same.” He claims, hilariously, that he’ll help grow the economy by 3 per cent a year and balance the books with nary a single cut – a feat no one but Bernie Madoff could pull off.

A lot of serious people share his concern. One of them is Bill Robson, the chief executive officer of the C. D. Howe Institute, a weekly adviser to the Bank of Canada. “It certainly does seem that the shadow of the pandemic will be over us for a long, long time to come,” Mr. Robson said the other day over the telephone. “In terms of fiscal impact, it kind of brought the future forward.” He sounded a bit like an undertaker, keen to sell a coffin but alert to the possibility of seeming too eager to close the deal given how fresh the loss was.

Mr. Robson is a fiscal conservative who likes a balanced budget – ”It’s such a keen discipline when you’re thinking about spending a dollar to ask yourself, what dollar do I not spend in order to make room for this?”– though he is not especially doctrinaire: When the Liberals first suggested a 10-per-cent wage subsidy at the outset of the pandemic, Mr. Robson urged them to increase it by a factor of eight. (They did.) But he worries that, with financial caution having been waived to soften the macroeconomic blow of COVID, public expectations are now permanently warped – and in ways they weren’t after the Second World War, the shining time Mr. Trudeau evoked at the outset of the campaign.

The postwar era deserves some attention. It was one of robust economic growth, for starters: Unlike our own, it wasn’t beset by amoral digital disruption and job-killing technological transformation. More to the point, once the war ended, the federal budget – up to 80 per cent of which had been devoted to military spending – ran big surpluses. That meant the government could both cut spending and spend more on new civilian initiatives, all within a strict budget envelope. “You did have a lot of restraint in spending overall,” Mr. Robson said, “because that was an offset to what was not getting spent after the war.” The afterglow of the country’s military spending inspired decades of university research and attention to education, the fruit of which we still enjoy today. The U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), for instance, was created by president Dwight Eisenhower in 1958 in response to the Soviet Union’s Sputnik launch. In the six decades since, its collaborations with universities, the federal government and the private sector have resulted in countless inventions: GPS, the personal computer, the internet and the Moderna vaccine are just a few of them. And yet military and defence spending as a fountain of future growth have been almost unmentioned so far in the federal election campaign.

Surviving the war produced modest hopes; surviving the pandemic has made us reckless. Maybe five years of world war is a long time to get used to having less than you want, long enough for it to become a habit. “There was a lot of desire to build a new world and take advantage of the desire for change that the war created,” Mr. Robson said. “But when I think back to that era, I don’t see the same kind of very expansive, no-limits thinking that seems to be not just here in Canada but in a lot of places these days.” The usual Ottawa negotiations between the Finance Department and Treasury Board “about whether a dollar spent on chocolate is better than a dollar spent on vanilla or strawberry – those conversations are no longer happening,” Mr. Robson insisted. “Everybody is saying, let’s have chocolate and vanilla and strawberry. We have all kinds of ambition to do things on the environmental front, the social services front, the health care front, all of them attractive on their own. But the essence of wisdom is to choose wisely. We should actually be choosing rather than just deciding that we’re going to have it all.”

Because whatever we choose, we’ll end up paying for it. One of Mr. Robson’s side interests is tax morale: the conditions that make people willing to pay their taxes, whether in the form of income taxes or wage controls or an HST that is suddenly five points higher (an idea that has surfaced of late in policy circles as a way to wipe out our COVID-related debt). “Peoples’ willingness to pay taxes seems to have to do with their sense of whether governments are using their money wisely,” Mr. Robson told me. “Right now, peoples’ willingness to pay tax is probably relatively high because it’s very clear that governments have been doing lots of things that people value.” But everyone agrees we can’t keep spending at this rate – and what will the winner of this election choose to spend money on once they have to choose, as they shortly will? Will it feed our short-term needs or our long-term future? No one on the campaign trail so far has been talking much about that, either.

Whatever else the pandemic did, it has revealed Canada’s desperate need for a new, ultramodern industrial policy – a specific plan, narrowly focused on clusters of expertise wherein governments, businesses and universities can collaborate to create daring new, green, sustainable intellectual property we can sell into the new “intangible” global innovation economy. “A new industrial strategy,” a recently reissued report from the Business Council of Canada concludes, “will be critical to rebuild Canada’s economy in the short-term and position it to be competitive in the long-term.” The mRNA technology behind the COVID vaccines is a perfect example of such a collaboration between medical research and private business that couldn’t have proceeded without government backing.

The Trudeau Liberals have been talking about industrial strategy since the days before Justin was elected prime minister. Multiple experts have identified agribusiness, advanced manufacturing (robotics), clean tech (the oil sands, among other dilemmas), digital business systems and maybe small modular nuclear reactors as potentially game-changing sectors where Canada could punch above its weight globally. (We already sell drought-management technology developed with federal government backing to California almond farmers, to cite just one example.)

“Some countries have used COVID to reposition themselves, and figure out what they want to be good at,” Mr. Asselin said. “Unfortunately, I don’t think we have come to this point yet.” Pause. “I’m hoping the government will be more focused on what it does and how it does it because of this crisis.” Mr. Asselin, a former policy adviser to Justin Trudeau, is the author, with Sean Speer, a onetime adviser to Stephen Harper, of North Star II, an urgent call for a modern, ultra-focused Canadian industrial policy for the digital era. Such reports are usually chloroform in print; North Star II is, unusually, a compelling and alarming read. It’s a measure of how quickly technology is changing that the authors have had to update the study three times in the past two years: As Mr. Asselin pointed out, artificial intelligence wasn’t even mentioned in the Liberals’ 2015 election platform, which he helped write. Now it’s a major component in Mr. Biden’s plan for the future.

“It’s easy to come up with an industrial strategy,” Mr. Asselin said. “But we are very bad at spending a lot of money with very little result. I’m worried we kind of screwed this opportunity.” Canada does too much basic research, and not enough of the applied industrial variety; we don’t hold on to our patents; and we have a habit of using government largesse for partisan political purposes, rather than judiciously, for the secular good of the economy.

But our biggest problem is that we don’t focus tightly enough. Why? Because the federal government is too big to run such a program efficiently. Our R&D spending is currently spread over more than 60 federal programs delivered by 17 departments. That has to change, very quickly: Germany, Australia, South Korea, Singapore, the United States and even Britain have all used COVID to develop industrial policies. We also need to be less cautious: The federal government spent $300-billion-plus addressing COVID, but not even $20-billion last year (which was more than we’ve ever spent before) on research and development. The Finns and South Koreans spend twice that much as a percentage of GDP.

Mr. Asselin believes that a Canadian equivalent of DARPA is the best way to create a more productive and profitable industrial strategy – a tiny, nimble but well-funded operation with only a few hundred specialist employees. Without groundbreaking, growth-producing businesses of the kind favoured by digital-era industrial policy, we won’t be able to pay our debts, never mind improve the lives of our citizens. “Then we’ll have a real challenge in front of us.” The spectre of Argentina beckons. The Liberal election platform promises a specific DARPA-style innovation hub, but the financial commitment ($2-billion) is minuscule enough to look like an afterthought. And none of the federal leaders have spent much time talking about innovation strategy – even though it is arguably the most important challenge we face.

What Mr. Trudeau and Mr. O’Toole are implying instead is that only a strong leader with a majority can lead us out of this morass. The facts suggest otherwise. Canada’s nimble response to the global pandemic – our aggressive vaccination rate, our procurement of vaccines without any manufacturing capacity, our modest death rate (fifth lowest in the world), our extensive supports – was delivered by a minority government. A crisis doesn’t require concentrated power so much as effective collaboration.

Back in 1945, after the world-altering global conflict Mr. Trudeau invoked two weeks ago in his opening election salvo, the prime minister of the day, Mackenzie King, also insisted he needed a strong majority to lead the country forward out of darkness. His reward? A minority government. The discipline of power is one thing. The discipline of a pandemic is another entirely.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article referenced a nationwide figure rather than the federal government figure. This version has been corrected.

Your time is valuable. Have the Top Business Headlines newsletter conveniently delivered to your inbox in the morning or evening. Sign up today.

Ian Brown

Ian Brown