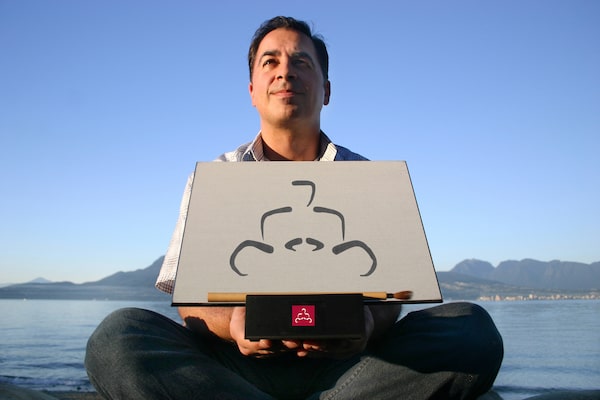

Eric Thrall is founder and chief executive officer of Buddha Board. The product is available in about 7,000 retail outlets in more than 30 countries.handout

Eric Thrall was watching eagles in a river valley north of Vancouver when the idea for Buddha Boards came to him.

His artist mother had recently introduced him to the technology for drawing on an electronic board surface, which inspired his aha moment: a board you paint on with water, the image disappearing as the water dries.

“It’s all about living in the moment,” says Mr. Thrall, founder and chief executive officer of Buddha Board.

That was in 2000. He incorporated the company in 2002 and got the boards into a few local stores in Vancouver, including the Vancouver Art Gallery gift shop.

He knew, though, that the U.S. market, with its much larger population, was the prize for a consumer product like his. He attended the San Francisco Gift Show in 2002, the largest trade show on the Pacific Coast at the time.

“That’s where it all started,” he says.

He landed orders for his first U.S. retail stores, and word of mouth brought more. Buddha Boards proved popular with museum and art gallery gift shops, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Smithsonian Institute.

Originally envisioned as a peaceful distraction for adults, toy stores began ordering in such numbers that it spurred Mr. Thrall to design two more versions catering to children.

Around 2008, Mr. Thrall made his first foray into Europe. Today, the product is available in about 7,000 retail outlets in more than 30 countries, but the U.S. still accounts for about 80 per cent of sales.

Mr. Thrall is reluctant to disclose annual revenues, but they are “double-digit millions per year,” he says. In addition to Mr. Thrall himself, the company employs two full-time staff members and up to four part-time contract staff, depending on the time of year.

Initially, Buddha Boards were manufactured in Canada but, in 2004, as the company began to grow, he was introduced to a Canadian living in China with the experience and contacts to set up manufacturing locally. As a result, Mr. Thrall moved his company’s manufacturing to China.

Just before the pandemic in 2020, by chance, he increased inventory in North America, largely avoiding the supply chain problems that plagued many companies throughout the pandemic. Still, Mr. Thrall says he struggles with having the boards made in China. While he says the production team is really good, toys made in China can carry a stigma.

It comes down to cost, though.

“That’s why everybody was producing overseas in the first place because the costs are easily half or even less,” he says. “It’s tough. If I did produce it here, then the retail price ends up being higher just because you have to.”

That’s the crux of the problem for any company manufacturing in China, says Marvin Ryder, an associate professor of entrepreneurship at DeGroote School of Business at McMaster University.

He notes that Canada has had several difficult years with China politically. Most notorious was the detention of Canadian businessmen Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig for nearly three years in what was largely seen as retaliation by the Chinese government for Canada’s arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou at the request of the U.S.

More recently, China has continued trade with Russia despite its invasion of Ukraine and calls from the G7 for an economic boycott.

The idea of onshoring – moving manufacturing back to Canadian soil – is politically popular but not terribly practical, Mr. Ryder says.

“The problem is finding companies that are capable of making these things in this country and at the volume and price point that you would like,” he says. “China has state-of-the-art modern manufacturing technology that can make things relatively inexpensively and in great volumes. If I need a million of something, I can go to China, place the order, and that order might be filled in two or three weeks. That would be very hard to do on this side of the pond.”

Despite the stigma, consumers don’t support onshoring with their pocketbooks, he adds.

“It just doesn’t matter to consumers. Price matters,” Mr. Ryder says.

Buddha Board has also struggled with copycat products, which Mr. Thrall says became a problem after the company started selling well on Amazon 10 years ago.

Although Buddha Board has trademarks, copyright and patents, he says there seems to be little interest in enforcing them.

“We do have to monitor Amazon all the time and send (legal) letters to knockoff companies because they’ll use the name Buddha Board, or they’ll use photos of our products,” he says. “It’s hard … but we’re lucky in the sense that these are classic knockoffs, really cheap and not very well made, so it hasn’t really hurt our sales much.”

Counterfeit trade accounts for between 2.5 per cent and 7 per cent of the world’s manufacturing output and has an annual worth of between US$461-billion and $1.7-trillion, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

The Chinese government has no interest in policing counterfeits, says Tatiana Astray, an assistant professor at the Lazaridis School of Business and Economics at Wilfrid Laurier University with expertise in the counterfeit economy.

She says that the federal government acknowledged the problem more than a decade ago, but little has been done. The Canadian Anti-Counterfeiting Network, a coalition of individuals, businesses and organizations, tries to raise awareness.

Patents are no protection, and she says many companies have stopped filing them because they’re just a how-to for counterfeiters.

“Legally, this is a high-profit, low-penalty crime,” she says.

She says that companies can only embed details into their products to help differentiate them from cheaper counterfeits and educate consumers, citing companies like Canada Goose and Nike that have had success with such campaigns.

“In the absence of good government policy or proper consumer education, that is something companies should be actively doing,” she says.