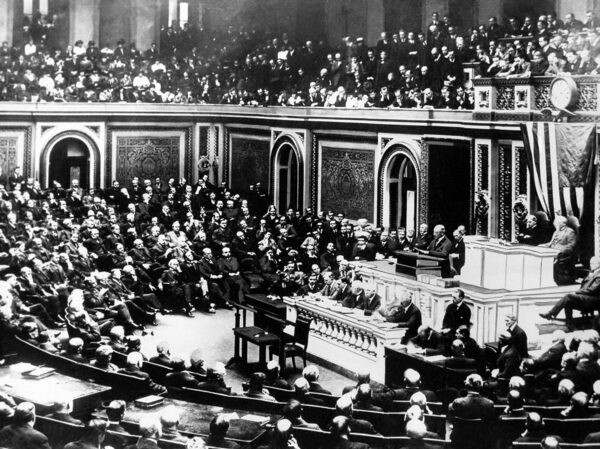

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson delivers a speech to the joint session of Congress in Washington, on April 2, 1917.The Associated Press

There’s probably one person you turn to, over and over again, when you need advice on work decisions. It might be a leadership coach or consultant, but more likely it’s your spouse, a trusted colleague, long-time counsellor, mentor or friend. Everyone needs someone to help sort through dilemmas.

Not much attention is paid to this advice relationship, even though it’s all around us. It’s a highly individualized, informal outgrowth of our needs and the wisdom, judgment and temperament of people we meet and keep close to us.

Two recent books on advisers to American presidents offered insights into this tricky role when played out at the highest levels of power. Join me in a trip through history that illuminates today.

Woodrow Wilson had 10 key advisers in his time as president of the United States, according to historian Charles Neu’s The Wilson Circle, and the makeup of that large constellation gives a sense of where counsellors can be drawn from. Two were wives, first Ellen and after her death, Edith Bolling Galt, who is assumed by many to have served as the country’s leader when he suffered a stroke and she blocked others from seeing him, issuing orders declaring “the President wants.”

Four were trusted operating officials, in his cabinet or near-cabinet: secretary of the treasury Williams Gibbs McAdoo, secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, secretary of war Newton Baker, and industrialist Bernard Baruch, who came on board to oversee economic mobilization as chair of the War Industries Board. The treasury secretary was thought to deliberately increase his influence by marrying the president’s daughter.

One unusual adviser was Gary Grayson, the physician Mr. Wilson inherited from his predecessor, who regularly lunched and golfed with the new president, a neat entry point for access and influence. Joe Tumulty, who served as Mr. Wilson’s secretary when he was governor of New Jersey, continued in that role during the presidency – the classic, young executive assistant with advice to offer. Similarly, famed journalist Ray Stannard Baker became an aide-adviser, as his press secretary at the Versailles peace talks, just as so many PR specialists do today.

The most influential, after the wives, was Colonel Edward House, a wealthy Texas political operative who bonded firmly with the President in their first meeting; Mr. Wilson said it was as if they had known each other forever. He was later to call Colonel House his “most trusted friend,” the only one in the world to whom he could open his whole mind. The quintessential adviser.

Indeed, when the President decided to marry Ms. Galt, he sought Colonel House’s opinion on whether that was politically acceptable and when to announce it to the public. Intriguingly, when the marriage between Bill and Hillary Clinton was on the rocks in 1998, following the admission of his relationship with Monica Lewinsky, the President turned to a modern-day equivalent of Colonel House, best friend and counsellor Vernon Jordan, to persuade his wife to stay in the marriage, according to Gary Ginsburg’s book First Friends.

Henry Kissinger, national security adviser and later secretary of state for President Richard Nixon, was accused of spending excessive time with his boss and once countered that when he wasn’t with the President somebody else was – proximity counts for an adviser. But Colonel House rarely was in Washington, with a home in New York, ties to Texas, and extensive travel to Europe, while still holding his sway. Mr. Jordan declined Mr. Clinton’s offer to be attorney-general, as the two arranged the cabinet after the election, saying “you need me more as a friend than in government.” Colonel House similarly resisted when offered any cabinet position except secretary of state, that was reserved for William Jennings Bryan. Advisers need not be part of the daily frenzy.

As typically happens, President Wilson’s circle had many jousts between them for advantage and sometime varying alliances to block rivals from influence. Advisers protect their access and influence. When his wife Edith was dismissive of Colonel House and Mr. Tumulty, Mr. Wilson wrote a long response, explaining that a president needs a diverse array of advisers, people whose talents supplemented his own.

When Colonel House was trying to meet with British foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey, U.S. ambassador to the United Kingston Walter Page advanced the case with these words, almost a job description for an influential counsellor, saying the Colonel was “the silent partner of President Wilson – that is to say, he is the most trusted political adviser and the nearest friend of the president. He is a private citizen, a man without personal ambition, a modest, quiet, even shy fellow.” Add to that job description President Wilson saying he liked having Mr. Baruch near him, and that he was “true to the bone. He told me what he believed, not what he knew I wanted him to say.”

Trust and candour are key. These are vital relationships, requiring loyalty, in the Oval Office or your office. Sometimes the leader and adviser grow apart, however. President Wilson felt Colonel House was too eager to compromise on his behalf in postwar negotiations and they never spoke again.

And while I have focused on advice, sometimes a leader just needs a friend. Bebe Rebozo and Richard Nixon would spend endless hours fishing, drinking and not saying much of anything to each other, Mr. Ginsberg notes in his book. Mr. Jordan and President Clinton loved to golf and share playful banter. But then, when a crisis or crucial decision arose, the President would tell his aides, “Call Vernon.”

Every leader needs a Vernon – or several of them.

Cannonballs

- A recent reunion of old work colleagues highlighted for me the influence leaders have on others – it’s almost scary – and the fact incidents you think crucial are long forgotten, while others you gave no significance to were important if not monumental in the other person’s life. Be mindful as you lead.

- On advisers: Politico reported in mid-April that after the end of the daily Ukrainian cabinet meeting – near midnight in that country, but afternoon here – Ukrainian Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal and Finance Minister Serhiy Marchenk would call our deputy prime minister Chrystia Freeland to chat.

- In contracts with marketing influencers, iron out who owns the content created on the brand’s behalf by the influencer. Marketing consultant Drew McLellan also recommends an Oops clause: The right to take down material injurious to your brand but since it also affects the influencer they might want some say.

Harvey Schachter is a Kingston-based writer specializing in management issues. He, along with Sheelagh Whittaker, former CEO of both EDS Canada and Cancom, are the authors of When Harvey Didn’t Meet Sheelagh: Emails on Leadership.

Stay ahead in your career. We have a weekly Careers newsletter to give you guidance and tips on career management, leadership, business education and more. Sign up today.

Harvey Schachter

Harvey Schachter