Kyle Scott/The Globe and Mail

In 2015, the Shaw Festival’s newly hired executive director, Tim Jennings, decided to buy pandemic interruption insurance. Five years later, that one move would help keep the theatre festival afloat and in much better shape during the COVID-19 crisis than its peers. Here’s the story in his own words.

We were eight days from our first performance when Ontario’s Minister of Culture called and told us to send everybody home. We had just come off the most successful year in the theatre’s history, and every dollar spent at the festival translates to about $6 or $7 spent in the Niagara area, which means we drive about $220 million in the local economy. So that was a hard moment.

When I started in 2015, we went through an insurance review, and we took out pandemic interruption insurance. That meant we were insulated against a fair amount of the damage caused by loss of performances, which gave us the optimism to keep all 550 of our people on, with the exception of some summer part-timers, throughout the whole pandemic.

Meanwhile, most of my industry was unable to work—they didn’t have the insurance we did. Every day, I’d hear them talking about laying off 30% to 50% of their staff. And although nothing here was in great shape, we stayed active at a level no one else was. As a charity, we’re here to serve the basic human needs that are met by art. But we’re also here to serve arts workers by creating a space where they can do excellent work. So the idea of offering stability in the middle of a storm was important to us.

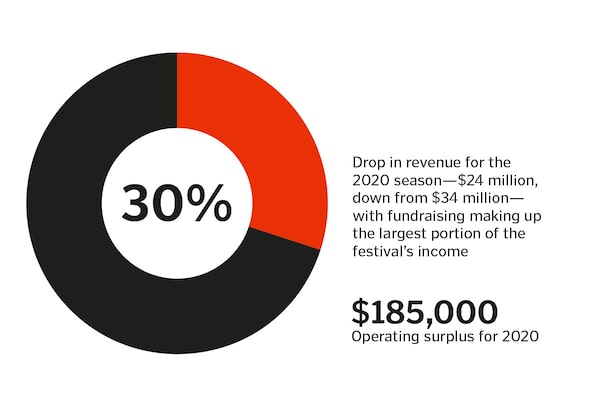

In May 2020, we realized we were going to lose a decent portion of the season. Our insurance is a net-loss policy, so it helped to keep us going. Fundraising was still going well. As for the wage-subsidy programs, almost all actors, musicians and directors are gig workers, so they weren’t able to get into them. So we let everybody out of their contracts and created a 16-week summer program doing education and community outreach. At the end of that, at least most of those people would qualify for EI. If each of those 96 workers created one project, whether it was running a book club or creating online content, that was effectively 100 projects put out into the world. It actually turned out to be much bigger—we reached over 130,000 people.

By February of 2021, we had decided to continue moving forward. So we offered everybody who had been in the 2020 season the opportunity to be in a smaller 2021 season. And then things changed again and again. It felt like every 72 hours, we were getting new rules and regs, and pivots had become pirouettes. Everybody was getting really burned out. But we created new outdoor staging structures and ways to perform.

We ended up having about 600 events over the course of the summer. So it was actually bigger in some ways than it normally is.

I can’t begin to say how much anxiety exists in this space. I’ve invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in new filtration systems and touchless ticketing and program systems. But we’re here to put good into the world, and all this has reinforced for us that the folks who make theatre are the resource. So we just keep trying to figure out how to create spaces where people can feel safe in a world where safety is really hard to find.

As told to Alex Mlynek

Your time is valuable. Have the Top Business Headlines newsletter conveniently delivered to your inbox in the morning or evening. Sign up today.