Noah Blackstein is vice-president and senior portfolio manager of Dynamic Power American Growth FundKailee Mandel/The Globe and Mail

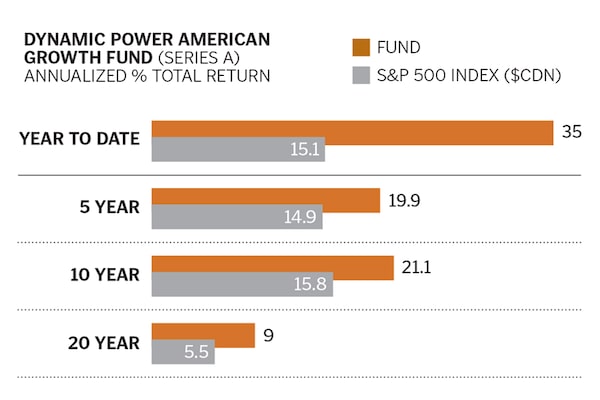

It’s very rare for a money manager to beat the index by a wide margin over two decades. But Noah Blackstein, who oversees more than $5 billion in U.S. and global portfolios for Scotiabank’s Dynamic Funds, has done it with his flagship Dynamic Power American Growth Fund (Series A). We asked the 49-year-old growth manager how he navigates through U.S. President Donald Trump’s tweets and why he finds yoga-inspired apparel retailer Lululemon Athletica a compelling investment.

How have you outpaced the Standard & Poor’s 500 over the long haul?

If you gave me $1 million in July 1998, that's worth almost $7.9 million today. The same million in the S&P 500 is worth $3.5 million in Canadian dollars.

We have more than doubled the S&P 500 return over 21 years. We tend to own 20 to 25 stocks. Consumer discretionary, retail, technology and health care are historically good areas where you find companies that can go from a few hundred million in revenues to tens of billions. The key to the success of the strategy is to stick to the discipline and not waver when you have a difficult year—no matter what people say.

How do you deal with President Trump’s tweets on U.S.-China trade that can roil markets?

I have gone through Presidents Clinton, Bush, Obama and now Trump. I take geopolitics and the macro situation as cards dealt to me. Until something macro impacts an individual company, I try not to be overly influenced. Volatility is not a measure of risk. For me, risk is the probability of a company going under. Reducing the China exposure in my global portfolio to 4% from over 30% last year was not a trade-war call. There was an unbelievable Chinese crackdown and a tremendous amount of regulation put on everything from video games to pharmaceuticals, social media and after-school education institutions. That made it very difficult for a lot of companies.

Where are you seeing opportunities?

We are in the midst of a digital transformation. Companies are shifting to the cloud for everything from human resources to supply-chain software. In this space, we own names like cloud-service provider ServiceNow and Paycom Software, whose products focus on payroll and employee recruitment.

Retailers are struggling. Why do you own Lululemon?

Lululemon has embraced digital in its stores and Web shopping. It has the right merchandising. And its new CEO, Calvin McDonald, has a pedigree from running U.S. cosmetic chain Sephora. Lululemon's men's business is also a huge opportunity—and yes, I am a customer. Their men's pants are unbelievably comfortable.

Do this year’s hot initial public offerings or cannabis stocks interest you?

The way IPOs are done today, a very small float is put out. The stock goes crazy for a short time, but then the lock-up period [for insiders] ends, and their shares can trade freely. That puts downward pressure on valuations and can provide a buying opportunity. We find a few interesting. As for cannabis, this phase is like internet stocks in the late 1990s—huge market caps but not a lot of earnings. There will be a big shakeout. If a company can grow rapidly over time and is profitable, maybe we'll look at it.

What are your best and worst investments?

From 2000 to 2011, we had winners like Apple and Google, and more recently, Salesforce.com. I think of my mistakes as companies I thought had fully played out. Adobe Systems is a digital-media software company that we owned for short periods.

I felt it was a mature, slower-growing company and didn't anticipate the acceleration in its business when it shifted to a cloud subscription-based model. I missed it.

What is your favourite investment book?

I read Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits by Philip Fisher in my early 20s. I had heard that [value investor] Warren Buffett's approach was influenced by Benjamin Graham and Fisher. Fisher was one of the few investors to write down his system of finding great growth companies. That book is still relevant today.

The Globe and Mail

More Wealth Ideas

What’s happening with Government Bonds?

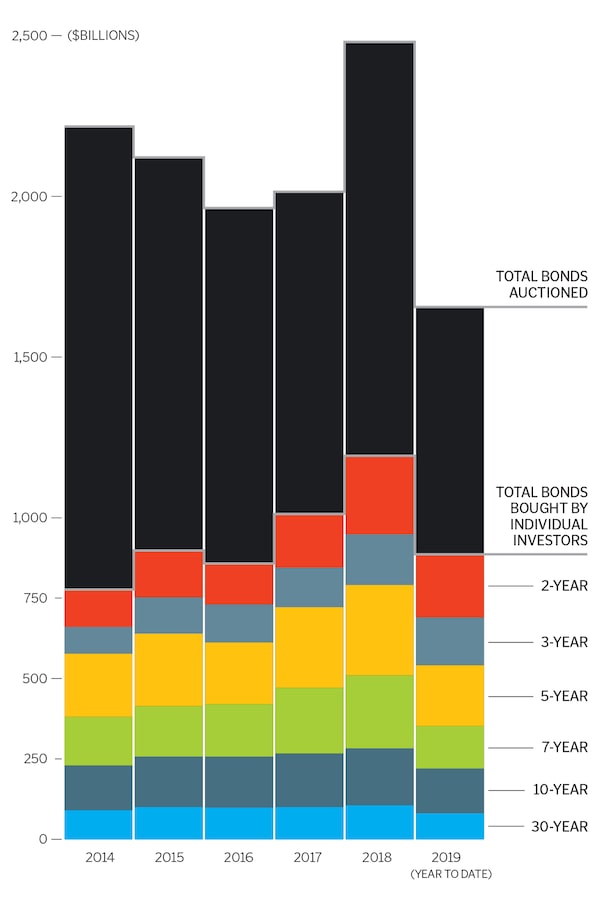

Government bonds are all the rage among investors amid concerns about the weakening global economic backdrop.

But the biggest source of money rushing into this safe asset class is surprising. Move over, sovereign wealth funds, life insurance companies and pension plans: The new top bond buyers are Jill and Joe Retail Investor.

The Globe and Mail

According to data from the U.S. Treasury Department, investment funds (a category dominated by mutual funds, which are largely the domain of retail investors) bought more than half of all newly auctioned U.S. government bonds in July. That reinforces a trend identified by The Wall Street Journal early in the summer: 2019 is on track to be a record year for bond buying among individual investors. Between January and May of this year, these investors accounted for 54% of the purchases of new government bonds sold at auction, up from just 20% in 2010.

Canadian numbers point to a similar trend. Canadian bond exchange traded funds saw the greatest net cash inflows within the ETF universe in the second quarter and first half of this year, according to Vanguard (using data from Morningstar).

What explains the attraction to bonds? Many observers point to the longer-term impact of our aging population: Older investors tend to lean more heavily on bonds in their portfolios.

In addition, individual investors recoiled from the stock market volatility at the end of 2018, which sent the S&P 500 down nearly 20% between October and late December. The trade war between China and the United States, along with slowing economic activity in Germany and China, surely haven't soothed any nerves.

“What we saw in the fourth quarter, when equities declined, was a shift in risk appetite, where investors were favouring safer fixed income assets over equities,” says Todd Schlanger, senior investment strategist at Vanguard. “In the first quarter, equity markets were positive and offset the losses we saw in the fourth quarter, but we haven't seen risk appetite recover yet.”

David Berman

How a family office can ensure generations of success

What is a family office?

A family office addresses the investment needs of high-net-worth individuals—but that's not the full picture. Family wealth management is much more complex than simply handling assets, says Greg Moore of Richter Family Office in Toronto. A family might also need tax and estate planning, financial reporting and philanthropy assistance.

There are two different types: single- and multi-family offices, which are exactly what they sound like. The first is set up by an individual family, while the second caters to a small group of families and is typically a pre-existing operation that can be contracted.

Why is it a good idea?

In a nutshell, setting up a family office guarantees the family fortune isn't mindlessly squandered. Ever heard the expression “shirt sleeves to shirt sleeves in three generations”?

It describes the erosion of wealth over a relatively short period of time. “An effective family office is designed to help ensure each generation is a wealth creator in its own right, building on the successes of prior generations,” says Moore.

How does one go about setting up a family office?

To get started, figure out whether you want to set up a single- or multi-family office. Tom McCullough, chair and CEO of Northwood Family Office in Toronto, says a $500-million net worth should be used as a threshold.

If your net worth is less than $500 million, McCullough recommends identifying your top three goals and then evaluating a handful of multi-family offices by those needs.

If you have more, consider setting up a single-family office, which will give you a higher level of control. It can cost two to three times more than a multi-family office—McCullough ballparks it at $1 million to $2 million per year.

Are there any downsides to setting up a family office?

Only the cost. “It comes down to numbers, and families considering setting up a single-family office will need to have a critical mass of wealth before it starts to make sense,” says Jeremy Martenstyn, a senior tax manager at BDO Canada LLP in Toronto.

What’s the bottom line?

In the end, says Moore, the primary goal of setting up a family office is typically continuity. “It's about providing the family with a resource to deliver support across generations,” he says. It also involves building a set of core values that can withstand transitions. “As most families that are in a position to set up a family office have sufficient wealth to sustain multiple generations, establishing the framework and governance to steward this wealth into the future is key.”

Sarah Treleaven