In August, 2019, the French village of Criquebeuf-sur-Seine held a celebration to mark 75 years since it was liberated from Nazi occupation by Canadian troops.Damien Bellière/Damien Bellière

Like many in his generation who fought in the Second World War, Keith Crummer didn’t share much with his family after he returned to Canada in May, 1945, having seen action as an infantry officer in France, Belgium and the Netherlands.

“My father never talked about it. Never, never, ever, ever talked about it,” his eldest daughter, Diane Teetzel, recalled, though she once saw him in the basement watching the movie adaption of The Longest Day, the bestseller about the Normandy landing. “Tears were rolling down his face. I just shut the door and let him be."

Then, a trip 45 years ago to France brought Mr. Crummer back to Criquebeuf-sur-Seine, a Norman village his regiment liberated in 1944. The Canadian soldiers had arrived just after the Germans nearly executed 63 local hostages.

When Mr. Crummer visited in 1974, he showed up unannounced. However, "word got around that my father was there and the mayor at the time came to him ... and they had a big celebration,” Ms. Teetzel said.

Criquebeuf’s mayor later sent a letter, thanking Mr. Crummer. “You and your brave soldiers have left an enduring memory and friendship in all our hearts,” it said.

Ms. Teetzel said her father was "flabbergasted, absolutely flabbergasted” by the villagers’ kindness.

Though Mr. Crummer has since died, his name still resonates in Criquebeuf decades later and a deep friendship now bonds the locals and his family.

Tucked against a tributary of the Seine River, Criquebeuf is a small community off the beaten path in Normandy. Visitors who make the 90-minute drive from Paris enter through a street still lined by old stone houses, Rue des Canadiens. Then, past the town square, named Hostages Place, sits a bridge that, since August, has been renamed after Mr. Crummer.

Two weeks ago, friends from Criquebeuf visited Ms. Teetzel in Chatham, Ont. Her family greeted them at the train station with a French flag. It was a gesture mirroring the hospitality she received when she went to Criquebeuf this summer and witnessed the renaming of the bridge to honour her father’s memory.

“We’ve become a big family. ... It’s a beautiful friendship,” said Marie-Josée Heitz, one of the three Criquebeuf residents visiting Ms. Teetzel.

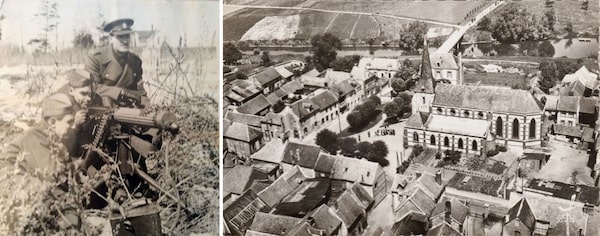

Keith Crummer, in left photo at top right, takes part in military exercises in Canada before he was sent overseas. His regiment landed in France in 1944 a few weeks after the D-Day landing, and they would soon find themselves under German fire in Criquebeuf, shown at right in 1958.Handout; Phylippe Detoisien

Today, the village has renamed a bridge after Mr. Crummer. Here, a Canadian flag hangs beside the plaque erected in his honour.Damien Bellière/Damien Bellière

Mr. Crummer was a 28-year-old employee at Chatham’s Union Gas Ltd. when he enlisted as a private at the start of the war in 1939. He was commissioned as an officer and, by 1944, was a major with D company of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment. They landed in France at the end of July, as Canadian and British soldiers still laboured to break out of the bridgeheads they established on D-Day, June 6. The regiment struggled in its first offensive operations. But within weeks, the bulk of the German military in Normandy had been surrounded and defeated in the battle of the Falaise pocket and the Allies rushed toward the Seine and Paris.

“Am in a little French house close to the road where our army is tearing by at a great pace," Mr. Crummer wrote in one letter to his wife, Frances. "We have been going night and day as you will have heard by now. The enemy is on the run burning his bridges behind him. We are not missing his convoys, passed through one the other night which stretched for at least 15 miles, every vehicle was destroyed, words cannot express the destruction.”

On Aug. 24, his regiment moved within 30 kilometres of the Seine, though muddy grounds and blown-up bridges slowed their advance. In Criquebeuf, meanwhile, the villagers were in danger.

Germans retreating by the village believed a local resident had wounded one of their soldiers. They rounded up 63 men into a church and prepared to execute them. It was no idle threat. In three occasions that summer, the Germans massacred hundreds of civilians in retaliation against the French Resistance. They hanged 99 men in the town of Tulle and deported another 149 to concentration camps. The following day, they killed 642 at Oradour-sur-Glane, then destroyed the village. The day after the Criquebeuf round-up, the Germans slaughtered 124 residents of the township of Maillé.

In Criquebeuf, Simonne Roman, who was then 13, remembered that the villagers came to ask her mother, Anne Fleck, to intercede. Ms. Fleck worked as a custodian for a wealthy Paris family that kept a summer mansion in the village. She spoke German because she was from Lorraine, a border area claimed by Germany. Ms. Roman said her mother arrived as the Germans were setting up machine guns and grenades to execute the hostages. For 45 minutes, Ms. Fleck pleaded with the officer in charge. She told him the villagers had never created problems before. “Maybe you have children,” she said, reminding the officer that both he and the villagers had children waiting at home.

Eventually, the officer told his men to leave the hostages and move on because the Allies were approaching. Ms. Roman remembered her mother returning to the mansion. “She was so relieved but very stressed, the poor dear.”

Anne Fleck, a local woman who talked the Germans out of executing hostages in Criquebeuf.handout/Handout

Two days later, according to the regimental diary, the first elements of the Lincoln and Welland Regiment entered the village. The Germans were still shelling the area. The Canadians fired back with their own artillery. Taking an abandoned boat, soldiers under Mr. Crummer’s command used shovels as paddles to reach the other bank of the Seine. “My company was the first Canadian troops to cross the Seine and stayed over all night," the major later wrote home. They held on to their bridgehead on the far bank without reinforcement for 12 hours, despite shellfire and some street fighting when a convoy of enemy vehicles passed by around midnight, Canadian military records say.

In the following weeks and months, the Lincoln and Welland Regiment faced more bitter fighting, in the canals of Flanders and the ice and mud of the Dutch island of Kapelsche Veer, in the winter of 1945. Mr. Crummer was wounded, then returned to Chatham to be a manager at Union Gas.

His wife had French relatives and friends. In 1974, they visited Georgette Testard, a Parisian cousin who had a holiday home in Elbeuf, eight kilometres from Criquebeuf. So Mr. Crummer decided to drop by Criquebeuf.

Mr. Crummer died in 1990. In the summer of 2014, Ms. Teetzel saw there were many events in France marking the 70th anniversary of the Normandy campaign. She looked at the letter from Criquebeuf. She wondered if the village had organized anything.

She found the town hall’s phone number and tried to get through in her best French. They connected her with Ms. Heitz’s son-in-law, Damien Bellière, a municipal councillor who informed her that the village’s celebration was scheduled to begin within days.

On short notice, Ms. Teetzel and one of her sisters, Joan Crummer-Rolland, flew to France, where they were greeted at Roissy Airport by Mr. Bellière and his brother-in-law, grinning and holding up a large Canadian flag. “Joanie and I, we just knew this was going to be the most incredible four days of our lives.”

Diane Teetzel and Simonne Roman, daughters of Keith Crummer and Anne Fleck, stand together at the 75th anniversary celebrations this past August.Damien Bellire/Damien Bellière

But that was only a start because five years later, last August, it was now 29 members of the Crummer family who were able to make it for Criquebeuf’s 75th anniversary celebration.

They met Ms. Roman, daughter of Ms. Fleck, who had saved the hostages, and agreed that her mother was a hero who deserved a medal.

There were fireworks. Bells tolled. Re-enactors wore vintage uniforms. Large banners, with Mr. Crummer’s photo and the Lincoln and Welland regimental badge, adorned the town square.

In an interview, Ms. Heitz’s daughter Bonny said it was important that Criquebeuf’s children could put a face to their Canadian liberators, a concrete reminder why their village still existed rather than be like Oradour-sur-Glane, never rebuilt and now a haunting memorial of Nazi atrocities.

Mr. Crummer, she said, represents “my village’s freedom. ... He was someone who crossed the Atlantic to risk his life for our country. They were men who enlisted to free a land that wasn’t even theirs.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Tu Thanh Ha

Tu Thanh Ha