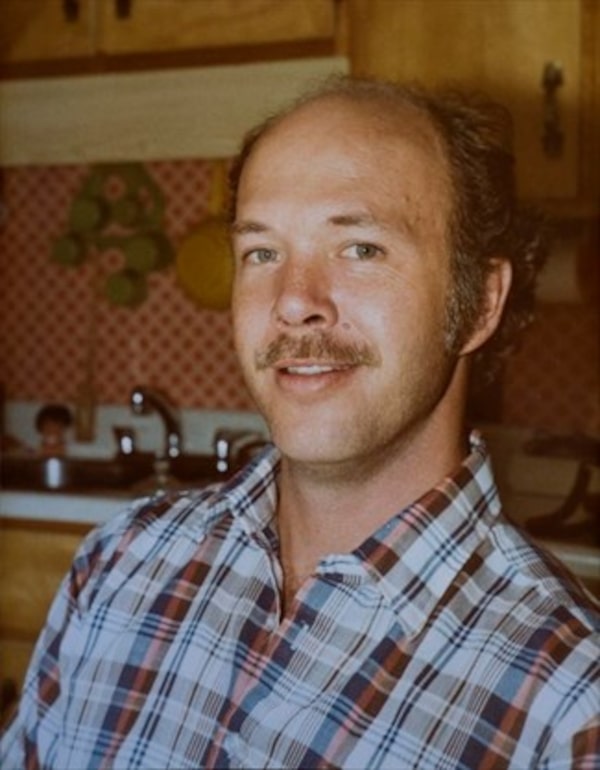

Lynden Wannan died of pancreatic cancer in 2001 at age 49, after collapsing on the factory floor at a Kitchener, Ont. tire plant. His widow has spent years fighting the WSIB to acknowledge his claim for compensation.Handout/Handout

Thousands of people in Ontario will get cancer from their job this year, but the vast majority will never receive compensation because of an outdated government system used to assess their claims, according to a new study commissioned by the province.

The independent study, requested by the Ministry of Labour, estimates about 3,000 new cases of cancer annually can be linked to people’s work. However, only about 170 of them are awarded compensation benefits through the province’s Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB). Hundreds of thousands more are exposed to “known or suspected” carcinogens on the job.

Just a small fraction of those people apply for and are granted compensation that they’re legally entitled to because of restrictive policies the WSIB uses to assess their claims, the report says. That includes overreliance on statistical models that eliminate claims that are outside sometimes arbitrary parameters.

That’s one of the reasons that the acceptance rate for cancer claims in Ontario, while in line with the Canadian average, is 2.9 cases per 100,000 workers. This compares with other jurisdictions such as Germany, where the acceptance rate is 15.1 per 100,000 workers.

“When people get diagnosed with cancer, their first concern is getting treatment and trying to survive. It’s only afterward people begin to get angry about this,” said Paul Demers, a workplace health expert at the Occupational Cancer Research Centre, who led the study.

Another significant problem is physicians often fail to recognize and report cases of occupational cancer, because most aren’t trained to ask patients about their work history and possible exposures, he said. That leaves patients on their own to identify potential job-related cancers, often years after they were exposed, and reduces the number of claims filed each year.

The report highlights a number of ways Ontario could improve how it prevents and handles cases of occupational cancer. These include collecting its own exposure data on workplace carcinogens, something the province stopped doing in the 1990s; hiring more staff with expertise in epidemiology, toxicology and exposure science; and expanding the lists of cancers that are automatically approved because of well-established associations with workplace exposures.

The Ministry of Labour has also not replaced staff with the expertise to investigate suspected clusters of cancer within specific industries, something that’s outside the specialty of government safety inspectors, the report said.

“This is not something you can hire consultants for,” Mr. Demers said. “Those agencies need to enhance their scientific capacity, and it’s been gradually eliminated. I think it’s something that needs to be rebuilt.”

The WSIB relies too often on outdated policies when assessing claims from someone with a history of smoking – often using smoking as a reason to deny a claim, despite evidence of exposure to well-known cancer-causing substances, such as asbestos, the report also shows.

Families of cancer victims say they hope the report can bring changes. The widow of Lynden Wannan, a tire builder from Kitchener who died of pancreatic cancer in 2001 at the age of 49, has spent years fighting the WSIB to acknowledge his case, citing well-known carcinogens used in the rubber industry. Mr. Wannan’s claim was denied because he used to smoke, and his mother had a history of breast cancer.

“It’s heartbreaking,” said his widow, Gayle Wannan. “We know his job is to blame, but they won’t accept it. They just don’t want to pay out.”

Improving the rate of accepted claims is critical, Mr. Demers said, because there’s a direct link between costs paid by the WSIB, which is funded by employers, and cancer prevention efforts. These cases cost the medical system many millions of dollars every year, costs that should instead be borne by the WSIB, he said.

The WSIB and the Ministry of Labour, which asked Mr. Demers to advise on how best to use scientific evidence when assessing claims, and to suggest practices used in other jurisdictions, said they’re reviewing the report.

“The scientific research related to occupational disease, particularly cancer, continues to evolve and we thank Dr. Demers for conducting this important study,” WSIB spokesperson Christine Arnott said in a statement.

“We are carefully reviewing the report and look forward to working with the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development and system partners to consider and address the recommendations.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Greg Mercer

Greg Mercer