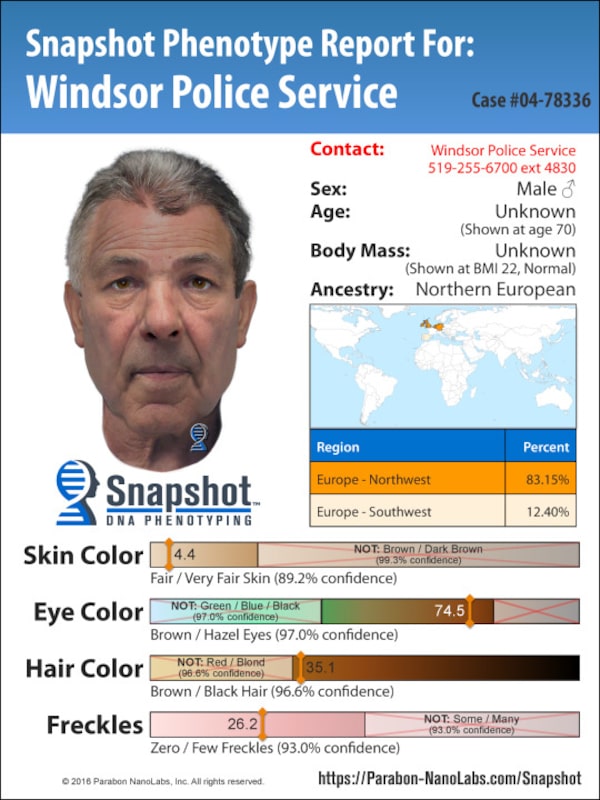

A Parabon NanoLabs Snapshot phenotyping composite prediction of a suspect wanted for questioning by Windsor police in the 1971 murder of six-year-old Ljubica Topic.Handout

Six-year-old Ljubica Topic was playing outside the family’s Windsor home on May 15, 1971, when a neighbour lured her away with the promise of pocket money. Police found her battered body that night.

Fifty-five-year-old Carol Christou, a mother of two, was last seen alive dining with friends at a Windsor pub on Sept. 13, 2000. Her body was found the next day in her home.

The killings remained unsolved for decades, tormenting the victims' families and city detectives. But in a surprise news conference last December, followed by a video statement this July, Windsor police revealed that they had solved both cases, while declining to name the killers or specify how they found them.

The Globe and Mail has learned that both investigations employed the controversial field of genetic genealogy, the same technology Toronto police used to solve the puzzle of nine-year-old Christine Jessop’s 1984 murder.

While Toronto investigators touted its use of the technique during a media conference last week, Windsor police kept their methods under wraps until confirming it on Friday.

“I can confirm that the [Windsor Police Service] used investigative genetic genealogy in the cases,” said Sergeant Steve Betteridge, a spokesman for the police force.

Guy Paul Morin was innocent. DNA in the Christine Jessop case proves it, once and for all

The Windsor cases bring the tally of publicly acknowledged Canadian cases solved via genetic genealogy to at least three – a far cry from the more than 100 murders and sexual assaults that have been cracked in the United States using the technique.

The true count is likely much higher, those involved in the investigations say, but police here prefer to not speak about their investigative methods, an approach that may be stifling debate about serious legal and ethical concerns.

“I think we’re on the precipice of an unmitigated disaster if we don’t start thinking through how this information can be used,” said Julia Creet, author of The Genealogical Sublime, a book tracing the histories of the private genealogical database companies now being mined by investigators.

“Without constraints, this will become a tool of mass surveillance very quickly.”

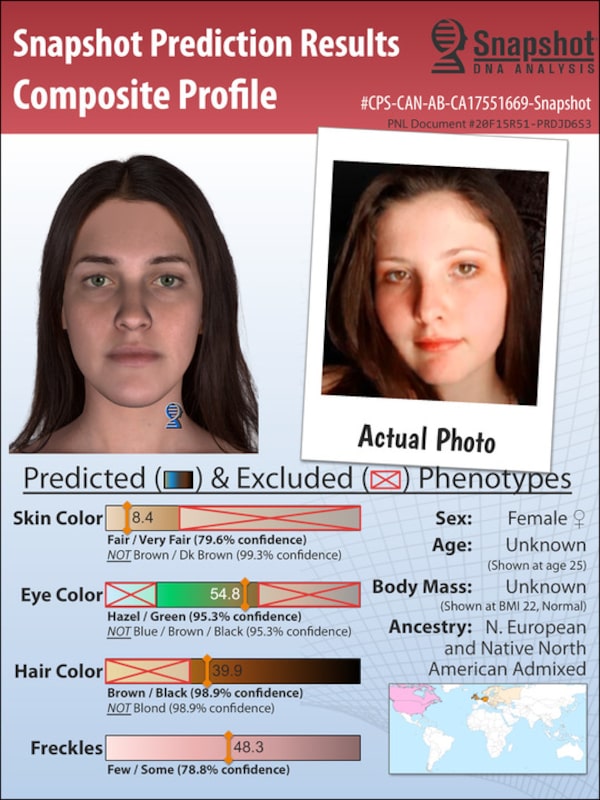

A composite prediction of Robert Steven Wright, 39, of North Bay, the man Greater Sudbury Police believe brutally murdered Renée Sweeney 20 years ago.Handout

Genetic genealogy is a marriage of cutting-edge DNA profiling and the ancient study of family trees that came to prominence slightly more than two years ago, when police arrested the Golden State Killer, a 74-year-old man who eventually pleaded guilty to a series of rapes and murders that terrorized Californians through much of the 1970s and 1980s.

The method only works when police have recovered a good sample of a perpetrator’s DNA.

In the Toronto case, for instance, investigators knew they had the killer’s DNA in the form of a semen stain found with Christine Jessop’s body. Last year, they submitted a sample to Othram, a Texas-based forensics lab devoted to law enforcement, where it underwent advanced genetic sequencing to determine the distinct familial nucleotide order of the killer’s DNA. Once Othram came up with a genetic family profile, it uploaded it to GEDmatch, a U.S.-based online platform that allows users to submit DNA profiles and map out familial connections.

Nina Albright, 21, whom Calgary police have laid charges against in the death of an infant dating back to 2017.Handout

The GEDmatch upload returned a list of distant genetic cousins of the unknown killer. Genealogists at Othram then used public records and information from police to fill out the many unknown branches on the killer’s family tree until they came up with Calvin Hoover, a man whose genetic profile and physical location at the time of the Jessop murder fit together.

Police matched the semen profile against a DNA sample from Mr. Hoover that was kept by the Centre for Forensic Sciences after his 2015 suicide.

While a subsequent news conference marked the first time a Canadian police agency had publicly credited the technique in solving such a major case, those on the front lines of genetic genealogy say officers have been using the technology far more than has been disclosed.

“Canada sat up and noticed [this technology] right away,” said CeCe Moore, chief genetic genealogist at Virginia-based Parabon NanoLabs. “They were very interested very early on in this idea.”

She should know. With dozens of solved cases to her credit along with a starring TV role on ABC’s The Genetic Detective, Ms. Moore’s profile attracts regular calls from investigators on both sides of the border.

“I can’t really say why they have handled it the way they have,” she said of the subdued Canadian approach. “I assumed it was just because Canada has such strict laws for privacy compared to what we have … . You guys really keep things locked down and private in most cases until the trial.”

A person of interest in two separate sexual assaults against young girls over the past several years in Waterloo, Ont.Handout

Demand from Canadian police has driven Wyndham Forensic Group, a forensics lab based in Guelph, Ont., to develop a genetic genealogy tool specifically for law enforcement. “We are doing work for police in this area and have been for a number of years,” said Valerie Blackmore, the lab’s founder and CEO. “Obviously I can’t talk about any of those cases. We don’t disclose who our clients are.”

Critics of the technique acknowledge the public good of solving difficult cases, but want to see legal checks.

The sudden surge of interest in genetic genealogy south of the border prompted the U.S. Department of Justice to issue a policy outlining ethical uses of the technology. Governments here have yet to lay down rules.

“The current state of the law is non-existent,” said Toronto-based criminal lawyer James Foy. “The police have not applied the technique before and it raises unique privacy and Charter concerns that will have to be litigated.”

One of those issues is the broad nature of consent that websites such as GEDmatch demand of users. GEDmatch and other sites used to allow unfettered law enforcement access to millions of profiles, but switched to an opt-in approach after an outcry of privacy concerns. The site now has around 300,000 profiles from people who have specifically consented to police searches.

But individual consent is complicated when it comes to DNA, which can act as a skeleton key to unlocking entire family trees. A single DNA submission can reveal the identities of distant relatives – dead, living and unborn.

“Your DNA isn’t just yours,” Mr. Foy said. “It’s shared with your family. That’s why the police want to use this technique. That DNA is shared is what makes it so powerful. But it’s also what makes it so dangerous and ripe for abuse.”

A composite prediction for a Saskatoon investigation to find the mother of an infant whose body was discovered in a downtown recycling bin in the fall of 2019.Handout

A 2018 study in the journal Science found that public genealogy sites could identify 60 per cent of Americans of Northern European descent. The researchers predicted that ratio would grow to 90 per cent within three years.

Investigators dismiss most of these concerns, saying they treat information from genetic genealogy less like evidence and more like tips from the public. The technology provides a lead; traditional investigative methods are used to confirm identities.

“Eventually this will play out in the courts,” said Detective Sergeant Steve Smith, the lead Jessop investigator. “But I think for 99.9 per cent of the Canadian public, if they knew a member of their family murdered a nine-year-old girl, they would want that person to be tried.”

He’d rather that governments provide cash than controls. “The big sticking point with genetic genealogy is having good genealogists and figuring out how to pay them,” he said.

Ms. Moore, the Parabon NanoLabs genealogist, says lawyers and lawmakers will have difficulty curbing the practice. “That’s because we were able to build this quietly under the radar for years before it got much attention and by the time people were starting to look closely, it was already done,” she said. “Pandora was already out of the box.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Colin Freeze

Colin Freeze Patrick White

Patrick White