Canadian jazz musician Guido Basso was a trumpeter, flugelhornist, arranger, composer, and conductor.Courtesy of the Family

In 1990, The Tonight Show trumpeter Doc Severinsen flew to Toronto on a matter of urgent business. He was infatuated with a version of Portrait of Jennie, an all-out flugelhorn number performed by the Canadian big band orchestra Rob McConnell & The Boss Brass. The sublime talent of Guido Basso was showcased on the recording.

In short, Mr. Severinsen wanted Mr. Basso’s evocative sound.

Mr. Basso had arranged to sell him a French Besson flugelhorn. To facilitate the transaction, he had four of them laid out on his pool table when Johnny Carson’s bandleader arrived by limousine. After sampling the instruments, Mr. Severinsen then began playing a trumpet. Seizing the opportunity, Mr. Basso began opening all the windows to his living room.

“I wanted my neighbours to think it was me playing the trumpet!” he later explained.

Self-effacement was part of Mr. Basso’s no-sweat charm. He could play the trumpet just fine, as anybody who saw him play the instrument in a gunslinger-themed duel with Al Hirt on The Johnny Cash Show in 1970 would know. His chief fame, however, was as a debonair balladeer on his instrument of choice.

“Guido Basso is quite simply the best damn flugelhorn player in the world,” the late Mr. McConnell said.

Mr. Basso was not one to blow his own horn, but he wasn’t above letting others do it for him. The noise carries further that way.

He died on Feb.13, in Hospice Quinte in Belleville, Ont., not far from his country home in picturesque Prince Edward County. His wife, Kristin Basso, said he had broken his femur in a fall recently and died of natural causes. He was 85.

A founding member of the Boss Brass orchestra, created in 1968, Mr. Basso’s sensuously lyrical flugelhorn and muted trumpet solos earned him international recognition. He forged a multifaceted career as a big band all-star, a first-call studio player on hundreds of recordings, a Juno-winning solo artist and a familiar face on CBC-TV in a variety of settings.

As a teenager in the 1950s, Mr. Basso backed Ella Fitzgerald and Johnny Ray as a member of the house band under the leadership of Maury Kaye at Montreal’s El Morocco club. Later in the decade he hit the road, first with Vic Damone and then with Pearl Bailey (who took him under her wing, calling him her son).

On television he was the musical director, featured soloist and occasional actor on Nightcap, a weekly show of satire and music sketches starring Alan Hamel among others in the 1960s. Mr. Basso co-hosted Mallets and Brass in 1969 with Peter Appleyard and led orchestras playing big band music in the early ‘70s on In The Mood and Bandwagon.

If Mr. Basso had people dancing as a leader of a Toronto-based society orchestra starting in the 1980s, he helped put them to sleep with his serene playing on Night Ride, Night Walk and Night Moves, Global Television’s trilogy of aimless a.m. journeying through downtown Toronto. Insomniacs would have noticed Mr. Basso’s name among the credits; others instantly recognized the soft and sure tone at work.

“I can pick Guido out after three notes,” said drummer Brian Barlow, a long-time friend and bandmate.

Probably less distinctively, he played harmonica – poignantly so at a lavish birthday party in 2003. Guest Elizabeth Bacon, the mother of politician John Tory, was noticeably upset that her son had just lost a mayoral election to David Miller, according to a pianist hired for the gig.

“As I played, I thought about her,” said Bill King, “and the feeling of what it was like to be such a public figure, then face defeat.” Sensing the mood, Mr. Basso approached the piano with harmonica in hand and suggested the mellow Someday My Prince Will Come. “Guido played it beautifully,” keyboardist Mr. King recalled. “It was nice and sweet, and it took the sting out of the moment.”

In 1994, Mr. Basso was named a member of the Order of Canada. On his bookshelf were Juno Awards for his 2003 album Lost in the Stars and for his flugelhorn contribution to 2000′s self-titled album by the Rob McConnell Tentet. He recorded several pop instrumental albums and jazz records under his own name, as well as gracing more than two dozen Boss Brass LPs.

He guested on countless recordings (jazz and otherwise) by artists including Anne Murray, Ian Tyson, Mel Tormé, Holly Cole, Sophie Milman and Mr. Appleyard. In Toronto he organized big-band concerts and performed with legends such as Dizzy Gillespie, Woody Herman, Benny Goodman, Count Basie and Duke Ellington.

Mr. Basso did not devote himself fully to a career in jazz, as doing so in Canada would not be an easy undertaking. Instead, he eschewed touring and took what he called “some nice bread gigs” in television and on the dancing-and-dining circuit in Toronto.

Whatever the setting, he was known as an affable, cool-headed professional. “He was smooth, and had a way of blending in with the music community,” Mr. King said. “He could navigate all waters.”

His musical legacy will be the distinctively emotional way in which he expressed himself. Whether on trumpet or the softer flugelhorn – he espoused the theory that one attacks the former and romances the latter – his work was inimitable.

“A lot of people say I’ve accomplished something, and that’s having a distinguishable voice,” Mr. Basso told The Globe and Mail in 1999. “Musicians from all over the world get in touch with me to find out what mouthpiece I use, what kind of horn I play. Which I find very flattering.”

On his trip back to Los Angeles from Toronto, Mr. Severinsen took four flugelhorns with him. Mr. Basso took the cash and accepted the inherent compliment, but kept his tone.

“Doc thought if he bought Guido’s flugelhorns, he’d sound like him,” Ms. Basso said. “That’s cute.”

He was born in Montreal on Sept. 27, 1937. A menopause baby, he was 14 years younger than his nearest sibling. His mother, Chiarina (née Tondi) Basso, was a homemaker. His father, Biagio Basso, was a presser and cutter in a clothing factory.

Both parents loved music, particularly opera. Originally Catholic, they converted during the Depression because they felt the Pentecostal church was more caring of families in need.

As a boy, Guido enjoyed the entertainment of baptism ceremonies. Years later he would tell the story of watching a little minister in a big tank of water practically drowning as he baptized ladies who looked like wet T-shirt contestants when they came up for air.

He began playing trumpet at age nine, studying at the Montreal Conservatory of Music. Growing up as an Italian, Protestant kid in a French, Catholic neighbourhood, he learned to fight with his left hand while using his playing hand to protect his teeth.

At age 11, he formed a quartet that played three hours a night on weekends at the non-licenced St. Hubert Spaghetti House. At one dollar per hour, each bandmember earned $9 each week – good scratch in the late 1940s, and more than enough for all the egg creams and comic books a boy could want.

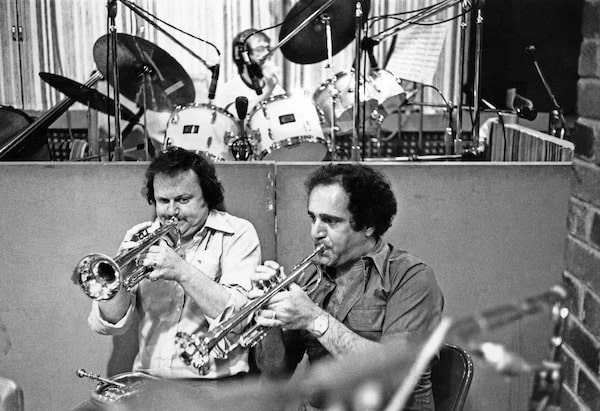

Horns Arnie Chycoski and Guido Basso of Toronto jazz orchestra, Boss Brass, on June 23, 1978.Handout

Because the wages wreaked havoc on the owner’s budget, the young musicians offered to play for free food instead. When they ate so much grub, the boys were quickly put back on a buck an hour.

At 13, he joined Al Nichols’s 15-piece dance band. Standing on a chair, he would solo in the style of the American trumpeter and bandleader Harry James.

In the Montreal of the 1950s, working players earned experience in a variety of musical situations in a city full of nightclubs. “You had to be versatile, you couldn’t be a specialist,” Mr. Basso told The Globe’s Mark Miller. “To try to make it as a jazz artist, you’d have starved.”

He settled in at the El Morocco, where he met a touring Tony Bennett. When Mr. Basso and the rest of the house band were late for rehearsal, the singer went looking for the musicians. He found them in a car, with the windows rolled up, smoking what could be described as a jazz cigarette. Mr. Bennett was invited in to indulge.

Later, Mr. Basso took Mr. Bennett to an Italian dinner prepared by his mother. The two musicians became good friends and remained so for life.

As a young man, Mr. Basso was a devotee of Harry (Sweets) Edison, a Count Basie Orchestra member known for his muted trumpet notes behind Frank Sinatra. When Mr. Basso got to meet his horn-playing hero, he told him that even though they both used the same mute, he could not get the same sound. Mr. Edison took Mr. Basso’s brand-new mute, threw it on the floor, stomped on it plenty, handed it back and told him to try it again.

It did not sound any better.

Mr. Basso’s fascination with the flugelhorn began when he heard Miles Davis’s use of the instrument on the 1957 album Miles Ahead. A few years later he found a flugelhorn for himself. It was one of two slightly battered ones that a Toronto music store had salvaged from a local school. (The other was bought by Freddie Stone, one of only three Canadian musicians known to have plied his trade within the Duke Ellington Orchestra.)

During an engagement at the Flamingo Las Vegas in 1960, Mr. Basso married his first wife, Darlene Anderson, named Miss Toronto one year earlier. His 1967 song Mia, Mia recognized the birth of their daughter Mia. (Mia Basso Noble died in 2013 of cancer.)

In addition to being one of the featured soloists in the Boss Brass, Mr. Basso played in orchestras led by Phil Nimmons and Ron Collier. Though he performed in Toronto nightclubs and hotel lounges in smaller groups, he preferred playing to leading.

“I don’t go knocking on doors and saying, ‘I want to put a jazz quintet in here for a week,’” he told The Globe. “It’s such a hassle. … I’d rather be in somebody else’s band: They point at me and I play.”

In the summer of 1976, Mr. Basso married his second wife, Kristin (née Stene) Basso. The ceremony was held in a log cabin in the woods. The jazzer Moe Koffman played the bridal march on his flute.

The couple eventually left Toronto for Consecon, Ont., where their spread was tailor-made for horseback riding and sumptuous meals with friends.

Although he recognized his elite musical status, Mr. Basso always thought he could improve on his efforts. In his last days, visitors and nurses would play his recordings at his bedside. Drifting in and out of consciousness, he praised the horn player.

“Guido didn’t realize he was listening to himself,” his wife said. “It was the only time I ever heard him acknowledge that he approved of how he played.”

Brad Wheeler

Brad Wheeler