Mireille Robillard with her father, Claude Robillard.

The phone rang and rang, but her father wasn’t picking up.

Mireille Robillard kept trying. Her father, Claude, had moved to the Ste-Dorothée long-term care home three years ago and had a landline in his room.

Finally, he answered. He had been walking in the hallway.

“You can’t do that – it’s dangerous for your health. It’s dangerous to the others. Everyone has to stay in their rooms,” she admonished him.

He had dementia, and his children and physician didn’t want to upset him, so the 82-year-old hadn’t been told he’d tested positive for COVID-19.

It was April 7. That period, between the last week of March and the first week of April, was a pivotal phase when COVID-19 overwhelmed Quebec’s elder-care facilities.

The same day Ms. Robillard was phoning her father, the local health board said it had tested all 174 elderly residents at Ste-Dorothée. It found 69 infected with the novel coronavirus. Eight had already died. Dozens of employees had also been exposed and had to miss work.

Later that week, Quebec Premier François Legault acknowledged the rising death toll in care homes, singling out facilities, including Ste-Dorothée, that were “in a critical situation.”

Once a retirement plum for Quebec elders, nursing homes are now symbols of neglect

Seniors’ care-home neglect is our national shame

Quebec’s move to allow seniors outside care homes affords the dignity we need in this pandemic

Signalling a shift in his government’s concerns, the Premier added, “I want this to become the priority for all Quebeckers: protecting our elders. We owe them that.”

Until then, Quebec feared that COVID-19 cases would overtake intensive-care units.

As the province moves swiftly to reopen schools and businesses, its government is still grappling with questions about whether it could have better handled the pandemic to lessen the death toll among seniors.

In the days before the first case in Quebec was confirmed on Feb. 28, the province completed protocols to triage infectious patients and redirect COVID-19 cases to dedicated hospitals. “Quebec is ready and mobilized,” the Health Department said in a press release.

Officials opened as many hospital beds as possible by postponing elective procedures and relocating patients to hotels or elder-care facilities.

Instead, the virus struck hardest in those very facilities for seniors. The ensuing devastation came in a part of the system that had long been underfunded, understaffed and packed with vulnerable people.

When the first person to die in Canada from COVID-19 was a resident of a North Vancouver care home, on March 8, B.C. health officials took early, aggressive steps to contain further outbreaks, contact tracing infections, restricting personnel movement and taking control of some care homes.

In Quebec, the reckoning came later. The focus was on ensuring hospitals could manage their COVID-19 caseloads. At the same time, because of staff shortages, the government allowed elder-care homes to recall employees who had been exposed to the virus but didn’t show symptoms, cutting short their quarantine.

It wasn’t until April 10, as the death toll surged, that Quebec announced an end to the transfer of patients to elder-care facilities. “We didn’t know at the time what we know now,” Health Minister Danielle McCann said, while still defending the decision to focus on freeing hospital beds.

That evening, the government learned that 31 residents had died at the Herron nursing home, where residents were found in squalid conditions. Horror stories from other facilities also emerged.

Today, 2,114 of the 2,631 Quebeckers who died of COVID-19 lived in an elder-care facility. That’s nearly twice as many as in Ontario, where 1,111 long-term care residents died. In addition, Quebec’s health care system is missing 11,600 workers, who are either sick, quarantined or unwilling to show up.

Facilities hit the hardest include Montreal’s long-term care homes Laurendeau (78 deaths) and Yvon-Brunet (more than 70), the Montreal Geriatric Institute (59) and Shawinigan’s Laflèche home (44).

At Ste-Dorothée alone, there were 84 deaths. More people died of COVID-19 in that single building than in all of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Atlantic Canada combined.

Ste-Dorothée is a public facility in Laval, a suburb north of Montreal, a five-storey building with a rehabilitation centre on its second floor.

Workers there complained that they lacked protective gear and had to move between infected and safe zones. Two employees said in interviews that there were no N95 respirator masks, only procedural masks, which weren’t readily available but instead locked in a manager’s office.

The Globe and Mail is not disclosing the names of the employees because they are not authorized to speak with the press.

“We didn’t have enough gowns, not enough masks. People were coughing,” one employee said, adding that staffers had no gloves while swabbing residents to test them for COVID-19.

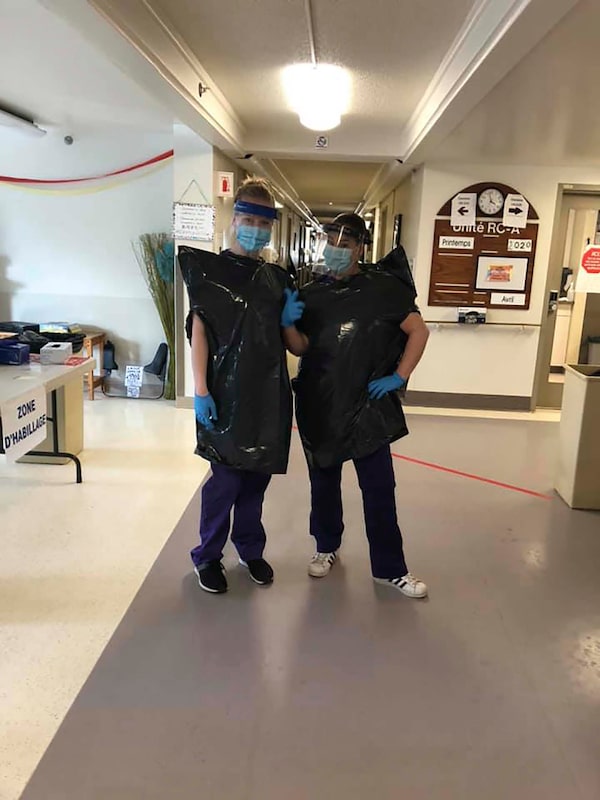

Two orderlies at a Montreal long-term care home are wear makeshift protective outfits made with garbage bags after the facility had run out of medical gowns. The photo was posted on Facebook on April 22, 2020.handout

The two employees also said there were limited numbers of medical goggles, so staffers paid for face shields out of their own pockets.

Despite the ban on family visits, Ste-Dorothée was still admitting hospital patients to its rehab unit, one employee said.

Judith Goudreau, a spokeswoman for the local health authority, said rehab admissions ended “as soon as the major outbreak at Ste-Dorothée appeared.” However, she would not give an exact date and did not say whether those patients had been screened for COVID-19 before their transfer.

The rehab unit still received patients until the first week of April, the employee said.

Conditions at Ste-Dorothée eventually led to a complaint to the provincial occupational-safety board. According to the ensuing investigation report, the outbreak began at Ste-Dorothée around March 22.

The same date is mentioned in a class-action suit launched by Jean-Pierre Daubois, whose 94-year-old mother, Anna José Maquet, was among the residents who died.

His statement of claim, which hasn’t been tested in court, said that on that day, an auxiliary nurse and an orderly had symptoms but were ordered to report for work anyway and were sent to a ward for residents with Alzheimer’s disease or cognitive problems.

Infected residents initially were confined to their rooms, with a warning sign on their doors. As their numbers increased, a COVID-19 “hot zone” was set up in the cafeteria, with curtains separating the beds. There were no toilets and no running water, so workers had to go outside the zone to fetch water to clean residents.

Some of the infected residents, who had cognitive issues, had to be tied up so they wouldn’t wander off, one of the employees said.

In the middle of one shift, that employee felt muscle aches and shivers. It was COVID-19. The employee had to be taken to Sacré-Coeur Hospital and isolated in a negative-pressure room. Doctors could remain outside and use an intercom. Medication was dropped through an opening in the door. Staff who came inside wore full protective gear, which they removed in an anteroom under supervision from another worker.

“Sacré-Coeur Hospital, it was just perfect in terms of protocols. Us, in care homes … we had nothing,” the employee recalled in an interview.

The other employee said so many nurses or orderlies fell sick or were forced to quarantine that a single staffer would have to handle an entire floor, with 20 or 30 residents.

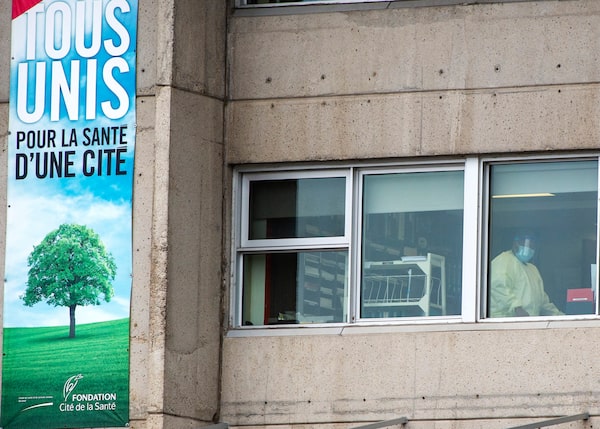

A health-care worker is seen in the window of Ste-Dorothée on April 9. More people died of COVID-19 in that single building than in all of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Atlantic Canada combined.Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press

The investigative report by the occupational-safety board says things took an acrimonious turn on April 3, when auxiliary nurses were told to perform procedures in the hot zone on residents who were wearing oxygen masks. Fearing this could create virus-carrying airborne droplets, they refused to work without N95 respirator masks. They received “intimidation and threats," their union said.

Asked to comment on the report’s findings and on other allegations involving Ste-Dorothée, Ms. Goudreau said that activities during the month of March followed standards set by the province’s Health Department and public-health institute. “These evolved daily as the situation and our knowledge of the disease changed.”

She referred to an April 17 press release announcing that better controls were set up at Ste-Dorothée and that more equipment and staff were redeployed there.

Audrey Power was in a group of six hospital nurses dispatched to Ste-Dorothée.

In a Facebook post that she gave permission to The Globe to quote, she recounted how they arrived in “a new and strange environment.”

They worked shifts of 12 to 16 hours. Their group shrank to two after the others developed symptoms or tested positive. She found herself responsible for 40 residents. She couldn’t take breaks to eat or sip water. She broke into tears on the job and had nightmares and insomnia. “I’ve barely been here two weeks and I am on the edge of burnout.”

As the new personnel also caught the virus, Mr. Legault exhorted others – medical employees, doctors, retired workers, nursing instructors – to go lend a hand in nursing homes. He also asked the Canadian Forces for help.

One who answered his call was a rehab therapist. The Globe is only identifying her by the pseudonym Louise because she is not authorized to speak on the matter.

Her first sight on arrival at a Montreal nursing home was bodies being wheeled to the morgue. The rapid decline of COVID-19 patients shocked her. Within hours, they lost their appetite, couldn’t move and groaned in pain. One woman clenched Louise’s hands and, between two moans, looked her in the eyes and said, “I am dying.”

Louise said she tried her best to comfort the woman and others while holding back tears. “I was dismayed seeing so many people die.”

A nursing-sciences student, Natalie Stake-Doucet also volunteered, at another facility. “I will never forget that moment, last night, at the end of the shift, when a colleague peeled off the little picture of a deceased person from the folder with the medication charts,” she wrote in a Facebook post that she gave permission to The Globe to republish.

They ran out of isolation gowns and were told supplies wouldn’t arrive for another week. One orderly posted on Facebook a photo of staffers having to wear garbage bags. The orderly was threatened with a reprimand but hours later they received new gowns.

Others were not so fortunate. Louise, the rehab therapist, eventually contracted COVID-19. “I’m messed up but I’m hanging in,” she told The Globe.

The Ste-Dorothée employee who spoke to The Globe and caught COVID-19 is dreading a return to work. “When I go back and I see all the patients I loved are gone, I don’t know how I will react.”

A health care worker brings supplies into the Ste. Dorothee, on April 7, 2020.The Canadian Press

On April 17, Mr. Legault offered a mea culpa. He said he had spent several days and nights wondering what he could have done differently. “I take full responsibility. We got into this crisis poorly equipped. And obviously, the situation worsened for all kinds of reasons. The virus got in.”

More recently, Horacio Arruda, Quebec's Director of Public Health, said officials didn’t appreciate the problem created by asymptomatic carriers. That, combined with the fact that some staffers worked simultaneously at several homes, contributed to the outbreaks, he said.

With the pandemic hitting hardest in the Montreal area, the Legault government is now talking about gradually reopening schools and businesses elsewhere in the province.

But for families of elderly patients, the anguish hasn’t faded.

Ms. Robillard said she bears no ill will toward the staff because “they did what they could with what they had.”

Her father, an easygoing retired administrator, was looking forward to springtime so he could go in the courtyard. However, after her April 7 call, it was hard to get news from him. “We wondered whether he suffered, whether he thought we had abandoned him. It was unsettling.”

Then one evening, Ms. Robillard and her brother were informed that their father had to be put on supplemental oxygen. Two days later, he was dying and receiving comfort care.

They were allowed to visit for compassionate reasons. Wearing a mask and gloves, she entered his room, touched his hands and his hair. “He was breathing but his mind wasn’t there,” she recalled. “So I bid farewell to my father.”

With reports from Janice Dickson and Kelly Grant

Sign up for the Coronavirus Update newsletter to read the day’s essential coronavirus news, features and explainers written by Globe reporters and editors.

Tu Thanh Ha

Tu Thanh Ha