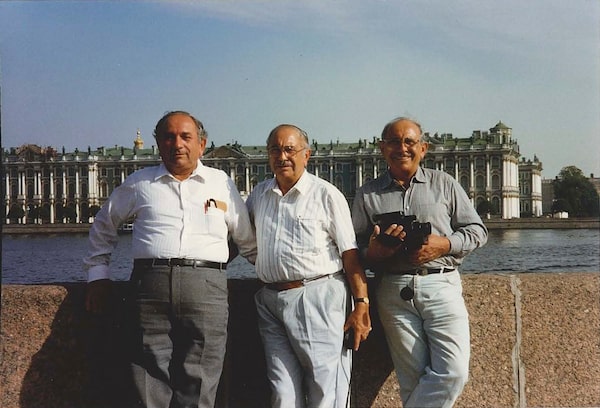

Hyman Itzkovitz, left, Jack Itkow and Sidney Itzkowitz, during a visit to the Belarus town of Mir in 1991. During the German occupation, the three brothers escaped from the Mir ghetto and joined the partisans fighting Nazi forces.Family handout

Sidney Itzkowitz wasn’t the kind to seek attention. After settling in Montreal in 1949, he worked as a cashier, attended night school, then joined his brothers in a furniture and mattresses business.

He had survived harrowing moments as a Jewish teen in Nazi-occupied Europe so, after he retired, he yearned to share those recollections. He penned a memoir for his children, which was eventually posted on a historical website.

He started carrying strips of paper printed with the link to that webpage. “When we saw him meet somebody, we were like, ‘How long is it going to take him before he fishes another one of those papers out of his pocket to give them to read his story’?” his daughter Selina said in a recent interview.

Mr. Itzkowitz is 94, the last survivor of five siblings. He is now too frail to share his story. But his memoir and video testimonies that he and two of his brothers gave years ago to the USC Shoah Foundation recount a gutsy tale of survival after their parents’ murder, escaping from a medieval castle and joining partisans in fighting against the Nazis.

Founded by film director Steven Spielberg, the foundation has collected thousands of testimonies from Holocaust survivors, though many, including those of Mr. Itzkowitz and his brothers, can’t be seen in their entirety without permission.

Mr. Itzkowitz’s experience highlights a lesser-known aspect of the Holocaust: The Jewish insurgents in the forests and marshes of Eastern Europe. Their guerrilla fight has been more widely recognized only recently, for example by the 2008 movie Defiance, in which Daniel Craig plays a historical partisan leader, Tuvia Bielski. The Bielski brigade was one of the units Mr. Itzkowitz and his brothers joined during the war.

“At first, I didn’t really believe I would survive, but I never gave up fighting,” Mr. Itzkowitz wrote in his memoir, From Mir to Montreal, posted on a University of Oregon history site.

His name at birth was Simcha and he grew up in the town of Mir, then in Poland but now part of Belarus.

They were five boys – Leibel, Zodel, Itzhak, Simcha and Chaim – raised in a Yiddish-speaking family. Their parents, Dovid and Mushka, owned a kosher butcher shop.

When the Second World War started, the Soviet Union annexed eastern Poland, including Mir. The Communist authorities confiscated the butcher store so the family grew vegetables and became friends with local farmers.

The medieval castle in the town of Mir, now in Belarus, which the Nazis turned into a ghetto that held 850 local Jews during the Second World War. About 200 of the prisoners managed to escape in a mass breakout in August 1942.Family handout

The Germans invaded in June, 1941. They set up a force of local police collaborators and immediately executed Jewish community leaders. Worse came on Nov. 9. That morning, Jews were ordered to come to the market square. The brothers scattered. “We knew something would happen,” Chaim said.

Simcha, who was 14, and 11-year-old Chaim hid behind a stack of storm windows in the attic. Local police came in and one man lit a match to check the darkened space. “I remember holding my breath,” Simcha said.

He was so terrified his stomach started to ache. The police didn’t see the boys and left. However, they went to the barn and found the elder Mr. Itzkowitz hiding there.

“I heard my father saying he would obey the order to gather in the town square with the other Jews. Then two shots rang out and my father was dead,” Simcha told The Globe and Mail in 2004.

His parents and six other relatives were among 1,500 Jews executed in Mir that day.

The 850 surviving Jews, including the five brothers, were confined in a ghetto set up in a rundown Gothic-era castle on the outskirts of town.

The three older brothers joined the ghetto’s underground, which was assisted by the police’s Polish civilian interpreter, Oswald Rufeisen who, unbeknownst to the Germans, was actually a fugitive Jew.

In the summer of 1942, Mr. Rufeisen tipped off the Jews that the Nazis planned a mass execution on Aug. 13. The underground group decided to try a mass escape the night of Aug. 10. “Many heart-breaking scenes took place,” Simcha said, because older people and women with children couldn’t join them and faced certain death.

Mr. Rufeisen helped the getaway by leading the police on a false alarm in another direction. Meanwhile, nearly 200 Jews broke free, jumping out of the castle’s windows after sawing through their metal bars, Chaim said.

In testimonies for the Shoah Foundation and for the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, other survivors described people jumping out of the windows, rolling down the slope, cutting through the barbed wired and dashing through the gaps.

Mr. Itzkowitz and his brothers were sheltered by the Krulutas, a family of farmers whose patriarch was a friend of their parents. They built a dugout bunker in the forest where, with three other fugitives, they spent the winter of 1942-43.

In the spring, they had to flee when the Germans raided the area. For a while they hid in the marshes. Simcha recalled being “exhausted, wet and freezing,” carrying potato sacks to supply their encampment.

In May, 1943, one brother, Itzhak, was able to get a rifle and joined a partisans’ brigade that allowed him to bring the other boys. After a four-day march, they reached the unit’s camp. Being 16, Simcha was sent to a workshop that converted unexploded shells into makeshift bombs.

The older brothers moved on to other partisan groups. Zodek was for a while a member of the Bielski brothers’ brigade. Leibel was shot dead in June in a clash with rival partisans who were anti-Semitic.

Simcha wasn’t in a safe spot either. The Germans attacked his camp during the summer. As they fled into a swamp, a partisan next to him was hit by the gunfire. “He asked that I please shoot him.” But a bullet grazed Simcha’s leg so he kept running. Separated from his group, he wandered by himself for two days, eating wild berries and drinking from puddles. “I have thought many times of the fellow who asked that I shoot him; I really could not do such a thing,” Simcha said in his memoir.

In 1944, the Red Army liberated the area. The brothers took part in a parade of 40,000 partisans in Minsk. Zodek and Itzhak then were inducted into the Soviet military but as they rode to the front, their truck hit a mine. Itzhak was killed and Zodek severely wounded.

Sidney Itzkowitz from 1947 in Vienna working for AJDC. Courtesy of the Family.Courtesy of the Family

Meanwhile, Simcha signed up for trade school to become a mechanic. He was sent to a remote town in the Ural mountains, where he faced hostility from the locals and anti-Semitism from his travelling companions. There actually was no trade school and he was pressured instead to work in iron mines.

He was able to leave in 1946 because he was a Polish citizen and the war had ended. Chaim had resettled in Montreal, under a program for Holocaust orphans. He then sponsored Simcha. Zodek, who initially moved to the United States, joined them.

Having arrived at different times, their names had been anglicized in different ways. Simcha became Sidney Itzkowitz, Chaim spelled his name Hyman Itzkovitz. Zodek went by Jack Itkow.

Hyman Itzkovitz founded a furniture company, Primo International. His brothers joined the business and Sidney Itzkowitz also bought a mattress company.

They were able to visit Israel and reconnect with Mr. Rufeisen, the interpreter, who had survived the war, converted to Catholicism, entered the priesthood and lived in a monastery as Brother Daniel.

In 2003, Mr. Itzkowitz read that Ottawa was trying to deport a Polish-born Montrealer named Walter Obodzinsky. The federal government alleged that Mr. Obodzinsky was a member of Mir’s wartime police auxiliaries – the men who took part in the massacre where Mr. Itzkowitz’s parents were killed.

Mr. Itzkowitz was outraged that the case had dragged on for four years. He hired a private investigator to find what happened to Mr. Obodzinsky. Unfortunately, the detective found that Mr. Obodzinsky died in March, 2004, before removal proceedings had concluded.

“I lay awake at night thinking about what I could do to see that the man was brought to justice,” he told The Globe and Mail at the time.

That 2004 Globe article focused on the Obodzinsky case and didn’t fully detail Mr. Itzkowitz’s past life. Last winter, in researching the deportation bid of another Nazi-era suspect, The Globe learned about Mr. Itzkowitz’s full story. His memory is foggier now and he is no longer able to give an interview but his previous testimonies helped recount the story of survival and defiance of the five brothers.

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Tu Thanh Ha

Tu Thanh Ha