An Inuvialuit leader wants the rare Western Arctic kayak held by the Vatican Museums sent back to the Mackenzie Delta region, where it was built a century ago.Willow Fiddler/The Globe and Mail

As they walked through a private display that had been prepared for them in the Vatican Museums on Tuesday, dozens of Indigenous delegates from Canada saw beautiful pieces of history from their home territories: Inuit carvings, a Haudenosaunee pipe given to Pope John Paul II in 1980, an 1831 wampum belt, Cree embroidered gloves and a Gwich’in beaded tunic.

The group’s members, who are in Rome this week for a historic series of talks with Pope Francis about the legacy of Canada’s church-run residential school system, experienced mixed emotions. For Marie-Anne Day Walker-Pelletier, a retired chief of the Okanese First Nation in Saskatchewan and a residential school survivor, seeing the artifacts brought back painful memories.

“Whether those artifacts have had the proper spiritual ceremony to keep them protected in that way – that we don’t know,” she said after the tour. These items, she added, “need to be restored and brought back and repatriated to those First Nations that are represented there.”

“You cannot reconcile your history if you don’t know what your history was. And if your items are sitting in other countries, certainly it does not fulfill the wholeness of your community as you are healing.”

Marie-Anne Day Walker-Pelletier, Chief of the Okanese First Nation.Fabrizio Troccoli/The Globe and Mail

Métis and Inuit delegations met with the Pope in a pair of private meetings on Monday; a First Nations delegation will have its own private meeting with him on Thursday. The Pope will then hold a general audience with all three groups on Friday.

The delegates are seeking an apology for the devastating harms children experienced at residential schools, along with reparations and access to the church’s historical records. And some are also requesting that the Pope return Indigenous artifacts, many of which are stored in the Vatican’s vaults and museums.

The Tuesday tour involved an hours-long visit to Vatican Museums, with a stop at the Sistine Chapel. It ended with a private showing of some of the museums’ ethnological collection, which is known as Anima Mundi. Some of the items had never been displayed before.

Labels on some of the artifacts said they were gifts, but in most cases it was unclear how they came to be in the Vatican’s possession.

Thread-embroidered gloves from the late 19th to early 20th century.Willow Fiddler/The Globe and Mail

Several delegates said they were angry to see sacred and personal objects housed so far from their communities. Some expressed awe at the objects’ beauty, and said they wished the items were more accessible. And many said they wanted to see them returned home.

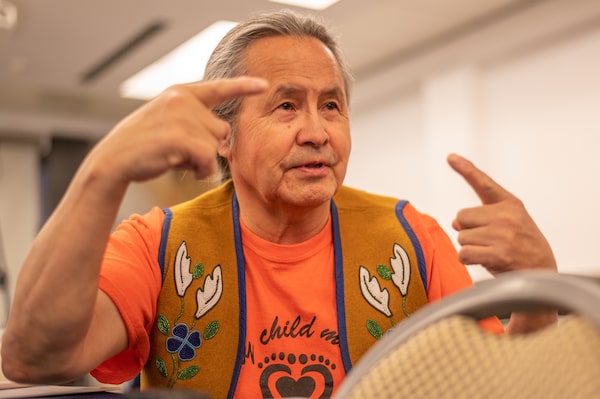

“I was a little bit disappointed,” said Assembly of First Nations Regional Chief Gerald Antoine, the lead delegate to Rome for the AFN and a residential school survivor. “I was very curious about the type of collections the Vatican has. There were just a few items that were put on the table … We didn’t really go into where all the collections are.”

“I welcome the gesture,” he said. But he added that he had hoped to look deeper into the collections, in order to gain an understanding of how the Vatican had acquired the items.

Gerald Antoine, Grand Chief of the Dehcho First Nations.Fabrizio Troccoli/The Globe and Mail

The Globe and Mail requested an interview with the museums’ curator on March 17, through the Holy See press office, and received no reply.

Some of the delegates saw the display as an important first step toward further dialogue about what is there and what should be returned.

The private display included a 4.4-metre sealskin kayak, at least a century old and one of only six of its kind known to have survived into the present. It has recently been a point of contention. The Vatican has said the kayak and other objects from the Mackenzie River Delta in the Western Canadian Arctic were gifts. Some Inuit are skeptical of that story.

After The Globe wrote a story about the kayak in November, Duane Ningaqsiq Smith, chair and chief executive officer of the Inuvialuit Regional Corp. in Inuvik, NWT, called for the kayak’s return. “This kayak is a piece of Inuvialuit history, made by Inuvialuit traditions. It is not ‘the Pope’s kayak’ and rightfully belongs to the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, where its lessons and significance can benefit Inuvialuit culture and communities,” he said.

Canada's Indigenous delegation visit the Vatican Museum in Rome, on March 29.Fabrizio Troccoli/The Globe and Mail

Inuk elder Martha Greig, a residential school survivor from Northern Quebec who was in Rome as part of the Inuit delegation, said she would also like to see the kayak returned. “It would be very nice to have it back,” she said as she was entering the Vatican Museums. “Not everyone has seen an original kayak, especially our youth.”

The kayak and other Indigenous artifacts from Canada now held at the Vatican Museums were collected in 1924 by Joseph Élie Breynat, a Roman Catholic bishop in the Mackenzie area. He shipped them to Rome, where they became part of Pope Pius XI’s world expo of Indigenous artifacts a year later. About 100,000 objects from the Americas, Africa, Asia and Australasia were put on display for a year, after which most of the vast collection was put into storage.

The kayak has been in and out of storage for the better part of a century and has not been on public display for at least two decades. It was brought out of storage for the Indigenous visit by Father Nicola Mapelli, curator of Anima Mundi, who spoke with the visitors from Canada.

Indigenous delegates from Canada were given access to the Vatican’s collection of Indigenous artifacts that few people have ever seen on March 29.Fabrizio Troccoli/The Globe and Mail

Anima Mundi intends to restore the kayak in collaboration with Inuvialuit. When Father Mapelli spoke to The Globe in November, he offered to travel to the Mackenzie region to learn about restoration methods, and he said the kayak could go on tour after it is repaired.

During Tuesday’s display of the kayak, Inuk leader Natan Obed, president of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, stood quietly. “For me, it’s a beautiful, functional part of our culture. And it’s wonderful to see it,” he said. “The circumstances of how it got here, I don’t really know.”

He said the kayak is a “living reminder of our culture” and that it is up to Inuvialuit, who made it, to work with the Catholic Church on stewardship of the item.

In November of 2021, the Vatican Museums opened part of their collection of Indigenous artifacts from Canada to The Globe including a rare, antique Inuvialuit kayak made of sealskin. This is what our correspondent saw.

The Globe and Mail

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Tavia Grant

Tavia Grant Willow Fiddler

Willow Fiddler Eric Reguly

Eric Reguly