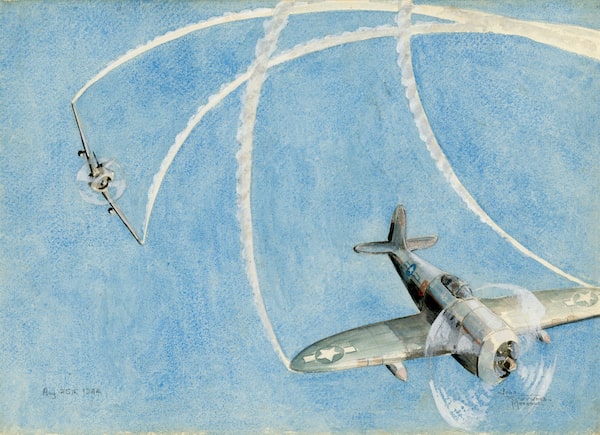

Fighter planes soar over Europe in a watercolour by John Fleetwood-Morrow, a Royal Canadian Air Force photographer who sketched hundreds of scenes from the Second World War.Paintings by John Fleetwood-Morrow • photos courtesy of family

No one would dare suggest treating war like a cartoon.

And yet, no one can deny that animation can be a powerful, engaging tool for reaching people of all ages.

Such is the thinking of Toronto documentary maker Matthew Corolis. This Remembrance Day, he will be releasing the trailer for his nearly finished documentary, The Reconnaissance Painter, an animated short that tells the story of John Fleetwood-Morrow, who served as a photographer in No. 39 Wing RCAF.

Composed of airmen from three Canadian squadrons, 400, 414 and 430, this ‘recce’ wing became known as the Eyes of the Army. It would play a critical role in 1944′s Operation Overlord, the code name for the Battle of Normandy, which began on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

It is a story that might never have been told but for a Grade 3 classroom nearly two decades ago and, years later, a chance meeting outside a Collingwood, Ont., grocery store between a retired teacher and a former major-general ...

But first let us return to the war.

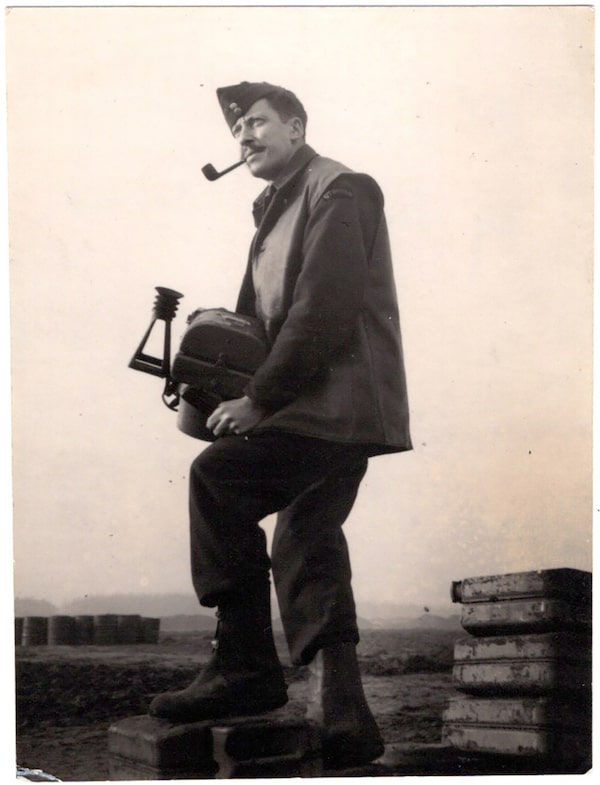

John Fleetwood-Morrow in the Dutch city of Eindhoven in 1945.

Based in an airfield at Odiham, England, a village in the Hampshire countryside, No. 39 Wing was pivotal to planning the D-Day attack, as Mustangs, Spitfires and Hurricanes equipped with cameras were able to provide essential information on German encampments, trenches, machine-gun batteries, truck convoys, terrain, bridges and buildings along the northern coast of France.

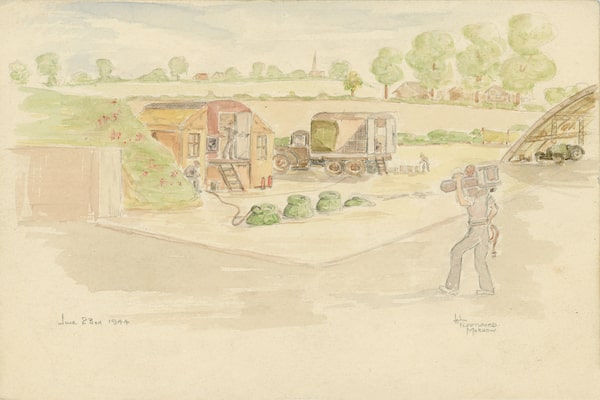

When the Allied forces landed successfully, the photographers and their film and developing equipment followed closely behind, to provide fresh photographic information on the shortest of notice. The film would be processed immediately in a developing truck, then raced by motorcycle back to central command or to officers at the front.

It was not as dangerous as actually being on the battlefield, but it had its moments. There were occasional attacks from the sky by Focke-Wulf 190s, tin hats the only protection for the men as they scrambled to safety.

An article in FLAP, a small publication the soldiers periodically produced, tells what it was like to be part of 39 Reconnaissance: “… In that frantic week before the zero hour of the Crossing, 39 Wing worked furiously to turn out photographs not only for their own army, the British Second, but also for both the First Canadian and American Ninth armies. In this one big job, undoubtedly the all-time epic of photo reconnaissance work, more than a million prints of all kinds were produced by the Wing.”

A photographer carries a camera to one of the developing trucks, mobile darkrooms that gave Allied forces valuable footage of the battlefield.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/BXBQTGPF5JCWVJ3WKJYR2X76WI.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/QJ4E5DF6ZZFMFHQ7N3DUN2EMLU.jpg)

Once landed in France, the Wing’s mobile print trucks were churning out prints at rates exceeding a thousand an hour.

“Never before had photographers been used to this extent in battle,” another issue of FLAP claimed. “… even section leaders went into action with copies of the same photos used by ‘brass hats’ to plan the attack.”

John Fleetwood-Morrow had trained as a photoengraver in England before emigrating to Canada in 1937, but he was also an accomplished amateur artist. He even joined Toronto’s Arts & Letters Club, where he became a lifelong friend of the Group of Seven’s A.J. Casson.

There being much down time near the front – the men would often wait hours for the pilots to complete their assigned reconnaissance missions and return with the film – Mr. Fleetwood-Morrow sketched hundreds of scenes in pencil and paint.

While many involved planes taking off, the trenches and pulverized battlefields, an equal number depicted ordinary life for the soldiers: visits to the beaches and cafés, trips to the dentist.

Always there was the human touch in a Fleetwood-Morrow painting. One piece shows a town that had suffered great destruction, buildings bombed, a hydro pole tilting dangerously, with a little boy approaching the truck with his hand held out. Mr. Fleetwood-Morrow has written “Cigarette pour mon papa?”

A boy asks soldiers whether they have a cigarette for his father. John Fleetwood-Morrow's work is full of poignant character moments such as this.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/C3DMFNJMTJHLFCTMM42KRNPZ4I.jpg)

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/5YV6GJ7RW5HD7JQL4A3VPIZ3C4.jpg)

A painting titled Happy New Year shows the carnage of Operation Bodenplatte on Jan. 1, 1945, when the Luftwaffe tried and failed to cripple Allied air forces in the Netherlands.

When the photographer-soldier was discharged on Feb. 20, 1946, he was awarded the 1939-45 Star, the France and Germany Star and the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal and Clasp. The real mementoes of his service, however, were his candid photographs and his art – all of which he later kept in a box stored at the family cottage near Perth, Ont. He eventually returned to photography as a profession, first in England, where he married Iris Cross, who had lost her pilot fiancé in the war, then back in Canada. Their only child, Jane, was born here in 1955.

Jane Fleetwood-Morrow became an art teacher, spending 21 years at Crescent School, a 109-year-old Toronto private school for boys that aims to build “Men of Character from Boys of Promise.” It was, says Ms. Fleetwood-Morrow, “a dream job,” as she was able to combine her love of art with her passion for teaching.

One such boy of promise was Matthew Corolis, who started Grade 3 at Crescent and loved the freedom of Ms. Fleetwood-Morrow’s art class. “I had no problem with kids making noise or getting up on tables,” says Ms. Fleetwood-Morrow, who retired in 2012, “so long as they were doing their work.”

Around Remembrance Day each year, Ms. Fleetwood-Morrow would bring the box to the school and show her classes her father’s photographs and art work. She would split the room in half, one side viewing and talking about the pictures, the other half sitting before a television set watching videos of Wallace & Gromit, British animated films about a cheese-loving, eccentric inventor and his anthropomorphic beagle.

Young Corolis loved the cartoons, but his great passion was sports, especially hockey and track and field. He would eventually go on to Queen’s University, where he ran track and intended to study business. He decided to take “a bird course” – film studies – thinking it would be an easy mark and a nice break from accounting and spreadsheets, which he was finding boring. It ended up his best mark.

“Why don’t I try this?” he asked himself. He moved on to Georgia, where he studied screenwriting at Savannah College of Art and Design and was soon making short documentaries. “I never really thought I was inspiring someone to go into film,” says Ms. Fleetwood-Morrow, who remembers Mr. Corolis as a “polite, quiet” student.

John Fleetwood-Morrow in the field.

Meanwhile, she was trying to find out more about her father’s work and experiences. Before his death in 1997, she had often sat with him and taken notes as he talked about the pictures and the stories behind them. She wanted to know more, so she and husband Mark Hord, head of Crescent’s middle school, made two pilgrimages to England and Europe, retracing the steps of No. 39 Wing.

A few years ago, she was shopping for groceries near her Collingwood home when she noticed a car with a veteran’s licence place and a face that looked vaguely familiar. It turned out to be author and retired Major-General Richard Rohmer, who lived in the area. In a remarkable coincidence, Mr. Rohmer was completely familiar with the important work of 39 Reconnaissance as he had served as a fighter pilot in 430 Squadron.

Though the retired war hero was then in his mid-90s, he had crystal-clear memories of the role “recce” had played in the invasion. Together, they went through the art and photographs while Ms. Fleetwood-Morrow took extensive notes.

“He gave me so much information,” she says. “It became a mission for me.”

Friends had long been telling her she should write a book about her father. “I’m not a writer,” she’d say. But another friend, Christine Cowley, was, and the two of them began working together in 2019. To mark this Remembrance Day, they will publish World War II Through An Unseen Lens: The Life, Service and Art of John Fleetwood-Morrow.

Yet another acquaintance, Lois Smith, whose son had been a classmate of Mr. Corolis, heard about the book project and contacted the young filmmaker, suggesting there might be a movie in all this. Last winter, Mr. Corolis drove to Collingwood for a COVID-masked meeting with his Grades 3-4-5 art teacher, and they agreed to work together to make a short film out of the sketches, drawings and paintings.

The pencil drawings and watercolour and oil paintings are brought to “life” with added frame-by-frame animation. The effect is quite captivating. Mr. Corolis is the film’s director and producer, with cinematographer James Burke and animator Brandon Park playing key roles in the production.

“This film makes it accessible to kids to learn about the war without the scary parts,” says the artist’s daughter.

“I want an audience where everyone can watch,” Mr. Corolis says. “I want to show a dark time in history that is approachable for kids.”

The considerable collection will then be donated to the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, where it will be archived and displayed.

“I know my dad would be, in his words, ‘tickled pink’ to see his work in a book.

“I will never see Remembrance Day the same way again.”

Remembrance Day reading: More from The Globe and Mail

Video: Tomb of the Unknown Soldier explained

Twenty-two years ago, the body of an unknown Canadian soldier was brought back from France and interred in front of the National War Memorial in Ottawa. Learn more about how it's become an integral part of war remembrance in Canada.

The Globe and Mail

First Person

It wasn’t until the end of his life that Dad told me about his Death March

For a soldier’s daughter, war is the hell that just keeps on giving

I’ve been to many Canadian war cemeteries but Ortona’s was more powerful than I expected

The art of war

Canadian war art remembers Indigenous peoples’ legacy on the battlefield

Biography sketches portrait of two notable Canadian war artists and their stormy marriage

Ted Zuber, veteran of Korean conflict, was Canada’s last official war artist