Empty shelves of children's pain relief medicine are seen at a Toronto pharmacy Wednesday, August 17, 2022.Joe O'Connal/The Canadian Press

As a neonatologist at BC Children’s Hospital and co-chair of a provincial program dealing with respiratory syncytial virus, Pascal Lavoie knows exactly how many cases of RSV are reported in the province.

In an average year, B.C. sees 1,450 cases of the common virus, which usually infects all children by the time they reach the age of two. But during the first full winter of COVID-19 in 2020-2021, with extensive public-health restrictions in place, there were only five.

Dr. Lavoie saw similar trends in Australia and the United States. However, in the summer of 2021, a major resurgence of RSV infections in those countries sent many children to hospital well before the usual fall onset of the virus.

In an article in the Canadian Medical Association Journal in July, 2021, Dr. Lavoie and two colleagues warned that an upswing of RSV infections “could stretch resources in pediatric intensive care units across Canada.”

The prediction came true. Last year, BC Children’s Hospital reported nearly three times the usual number of RSV infections in kids under 3. Other provinces, such as Alberta, also had a higher-than-usual number of RSV-related hospitalizations.

Return of seasonal flu, RSV and other viruses could spell disaster for older Canadians, experts say

By many accounts, this year is shaping up to be worse for children’s hospitals, according to nearly a dozen pediatric specialists interviewed by The Globe and Mail.

RSV is only one of a handful of viruses in circulation. In Alberta, for instance, many children coming to the emergency room are sick with influenza, said Stephen Freedman, an emergency physician at Alberta Children’s Hospital in Calgary. “Right now, it looks like influenza is probably the predominant virus we’re seeing driving kids in hordes to the emergency department,” he said.

A spokesman for Alberta Health Services declined to provide occupancy rates at Alberta Children’s Hospital but said the emergency department is very full and that illness and fatigue among staff are adding to the challenges.

In Ontario, pediatric hospitals are being forced to cancel surgeries, specialist clinics and diagnostic procedures “to free up physicians, staff and clinical spaces for children with very serious respiratory conditions,” according to Anthony Dale, president and CEO of the Ontario Hospital Association.

The Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario has been running over capacity for weeks and had to open a second pediatric intensive care unit. On Friday, McMaster Children’s Hospital in Hamilton said it’s running at 140-per-cent occupancy, with emergency wait times as long as 13 hours.

A sign directing visitors to the emergency department is shown at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Friday, May 15, 2015 in Ottawa.Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

And at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, surgeries were being limited to prioritize urgent procedures, as its ICU operated at above 127-per-cent capacity for several days last week – with more than half of those patients on a ventilator.

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, flu activity across the country increased “steeply” at the end of October, reaching more than 5-per-cent positivity among swabs done in clinical settings looking for a variety of respiratory viruses. Nearly 60 per cent of detected flu cases were in children and teens. The agency said it will declare a flu epidemic Monday if the numbers remain above that threshold at the start of November, marking an unusually early start to the flu season.

While the country did experience a resurgence of RSV last year, many parts of the country still had mask rules and other restrictions in place, which likely helped reduce the spread of the virus. This year, there are few restrictions and more in-person activities, which may explain why so many children are being infected with RSV and other viruses.

“There really are limited restrictions on activities and behaviours,” Dr. Freedman said. “What that’s leading to is rapid spread of viruses in a population of children who have been unexposed.”

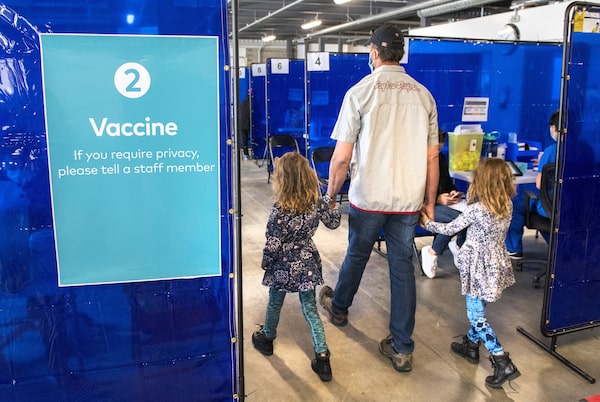

A man arrives with two young girls for his shot at the COVID-19 vaccination clinic at the Ontario Food Terminal in Toronto on Tuesday May 11, 2021.Frank Gunn/The Canadian Press

Children typically became infected with RSV before age two. While it’s possible to get the virus more than once, a child’s first exposure to it is usually the worst. But COVID-19 restrictions led to a decrease in the spread of viral illnesses, meaning a huge cohort of children who may never have seen the virus are all being exposed at the same time.

There’s evidence to back this up. In a study published last May in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, Dr. Lavoie and colleagues discovered a major drop in RSV antibody levels in pregnant women and infants one year into the COVID-19 pandemic.

The lack of exposure could help explain why more two- and three-year-olds are coming to hospital for treatment of symptoms of their first RSV infection.

On social media, some users have speculated that reduced exposure to viruses has damaged the immune systems of young children, which is sending more to hospital as a result of RSV. But there is no evidence to support this.

“Immune systems are pretty robust,” said Catherine Hankins, professor in the School of Population and Global Health at McGill University and co-chair of Canada’s COVID-19 Immunity Task Force. “It’s a delayed exposure, but there’s no indication that their immune response is in any way compromised.”

Jim Kellner, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Alberta Children’s Hospital, said there’s also no evidence to support the idea that children who had mild cases of COVID-19 are more susceptible to severe bouts of RSV or other respiratory illnesses.

While RSV season is hitting earlier and leading to extremely busy hospitals, Dr. Kellner said there’s no indication a higher proportion of kids are becoming seriously ill as a result of the virus. There are just a lot of kids getting exposed to the virus at once, he said.

There are viruses, notably measles, that can lead to long-term immune system damage, which is one reason vaccination is so important. Dr. Kellner added that children and adults who fall moderately or severely ill with the flu, COVID-19 or another virus may be more susceptible to other health problems for weeks or months after.

Another reason pediatric facilities are struggling is owing to serious staffing shortages, which are being felt across the health care system. Many health care workers are facing high levels of exhaustion and burnout, with some choosing to leave the profession.

The surge of respiratory viruses and subsequent crises in many pediatric facilities has prompted numerous health professionals and hospital executives to call for a return to mask mandates to help ease the pressure.

Experts say they’re also concerned over the fact too few children are vaccinated against the flu and COVID-19. In Alberta, only 7.5 per cent of one- to four-year-olds have gotten a flu shot. At the national level, only 1 per cent of children under 5 have received two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine.

“Kids and many adults don’t have a lot of immunity right now to the strains that are currently circulating,” Dr. Freedman said.

With a report from Salmaan Farooqui

Carly Weeks

Carly Weeks