Abraham Natanine is pictured with his youngest daughter in an undated family photo. He was shot dead by police on May 5, in Clyde River, Nunavut.Courtesy of Michelle Illauq

The mayor of a hamlet in Nunavut whose son was killed in a police shooting earlier this year is telling residents to film their interactions with the RCMP for protection.

“There’s lots of violence happening from the police, and I just want to encourage people to film what they can,” Jerry Natanine, whose son Abraham was killed on May 5 in Clyde River, said in an interview.

The 31-year-old was about to welcome his fifth child and studying to be a plumber when he was shot in front of his girlfriend, Michelle Illauq.

The Ottawa Police Service is investigating the Mounties' actions that evening, one of five the service launched into violent incidents – two of them fatal – involving the RCMP in Nunavut this year.

In a press release, the police said officers in Clyde River, which is on the northeast coast of Baffin Island, were responding to a “disturbance at a residence.”

Ms. Illauq says the force used against Abraham Natanine was unnecessary and his death could have been prevented had police used other means to defuse the situation. She also alleges she was treated improperly after the shooting.

She and Jerry Natanine say they have been told little about the status of the police investigation since that night.

“We are left in the sidelines, trusting a process that for many, has proven hard to trust,” said Ms. Illauq’s lawyer, Qajaq Robinson.

But Mr. Natanine says history tells him to expect very little from the investigation. He hasn’t seen accountability in the past and isn’t expecting it in his son’s case either. “All of us already know what’s going to happen: nothing,” he said.

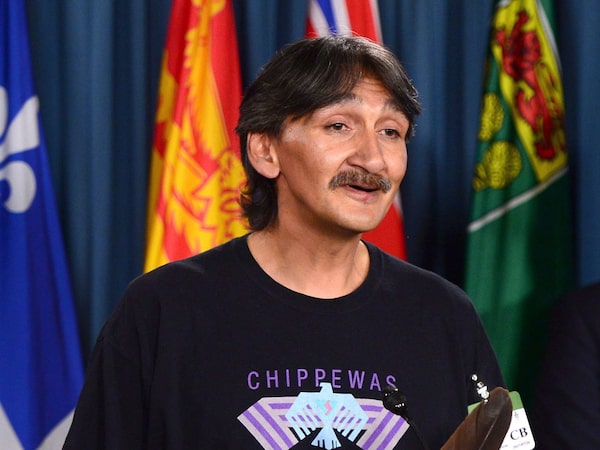

Jerry Natanine, Mayor of Clyde River, Nunavut, is photographed in Ottawa in this file photo from July 26, 2017.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

Last week, the government of Nunavut tabled legislation to allow investigations of serious police incidents to be contracted out to an independent agency, as is done in much of the rest of Canada. It would also permit the territory’s justice minister to appoint a civilian monitor and cultural adviser to investigations. However, it doesn’t rule out letting another police force investigate.

Ms. Robinson, a former commissioner of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls Inquiry, said the proposed legislation is a step in the right direction, but while it creates the opportunity for more oversight, it doesn’t guarantee it.

“The devil will be in the details,” she said, noting that the bill would not set mandatory transparency standards or timelines for reporting, and would leave much to regulations that have yet to be determined.

The government’s plan also would not allow the proposed civilian monitor to review past police investigations.

Changing that is “imperative for the residents of Nunavut, but also for the RCMP,” Ms. Robinson said. Goo Kingnuatsiaq, the father of the first Inuk man to be shot dead by police this year, also wants his son’s case reviewed. In August, an investigation by the Ottawa police cleared RCMP in the February death of Attachie Ashoona, but Mr. Kingnuatsiaq disputes the police characterization of events.

Nunavut Justice Minister Jeannie Ehaloak told The Globe she is open to a review of past investigations if the territory’s MLAs support the idea. Nunavut’s legislature operates on a consensus model of governance, without political parties.

If the extra review doesn’t happen, Ms. Robinson said, the RCMP’s efforts to build trust will continue to be “haunted by the mistakes of the past.”

So far, neither the RCMP nor the Ottawa police force has committed to give Abraham Natanine’s family the final report, she said.

“You are not going to have the general public believe you when you say: ‘Trust me, I did it right behind closed doors,’ ” Ms. Robinson said.

The lack of information doesn’t make sense to Ms. Illauq, who said she should be the “first person” to learn about developments in the probe.

She’s raising an infant son and young daughter without their dad, who she described as a dedicated father and her daughter’s “No. 1 person.” Abraham Natanine’s three other children are being raised by his parents and other relatives.

Because Ms. Illauq could be called as a witness in future proceedings, Ms. Robinson advised her against disclosing details of the interaction with police. But Ms. Illauq said “he didn’t have any weapons or anything in his hands” when he was shot. Ms. Robinson said the incident was prompted by an alcohol-related argument.

Ms. Illauq said her concerns about that night go beyond the shooting.

The same officers detained her overnight, saying she was drunk, which she disputes. She was released without charges. Similarly, Mr. Kingnuatsiaq said police detained him without cause on the night of his son’s death and he was released with no charges.

Ms. Illauq said she wasn’t given food, water, toilet paper or a blanket while she was in custody.

After "losing someone you loved, you shouldn’t be in the drunk tank,” she said. “I wanted to be with my daughter.”

Citing the investigation, the Nunavut RCMP declined to comment on the details provided by Ms. Illauq.

Research done in 2014 for the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP calls the practice of police investigating police problematic, and says it is no longer viewed as defensible.

Benson Cowan, the chief executive officer of Nunavut Legal Aid, said there’s not just a problem with perception when police investigate police.

“When other police forces investigate police officers, they tend to manage those investigations in a way that is either explicitly or implicitly sympathetic to the police force,” he said.

He added that the proposed oversight model needs to be more rigorous.

“The employment of a civilian monitor and a cultural liaison is a positive element and a good development, but it should be mandatory in all cases, and not subject to the discretion of the minister of justice,” he said. “There should be no discretion. Police should not be investigating police.”

Building trust is all the more crucial for the Mounties in Nunavut, NDP MP Mumilaaq Qaqqaq said, because of their troubled history with residents since the national force started policing the region in the mid-1900s.

The RCMP’s years-long slaughter of Inuit sled dogs and its involvement in forced relocations and removing people from their families for tuberculosis treatment are part of an "unspoken history” shaping distrust, she said.

“RCMP members need to have an understanding of the history. Understand what your uniform represents when you walk into a community,” she said.

Ms. Ehaloak said she doesn’t personally have concerns with the current police oversight, but she understands residents don’t trust it. She said how much information is disclosed from the new investigations would be determined on a case-by-case basis. The bill will be debated in the legislature next year.

“This is the way this government is being responsive to what Inuit in Nunavut want. And we have to ensure that our culture, our Inuit societal values, are being addressed.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Marieke Walsh

Marieke Walsh Sean Fine

Sean Fine