Many Canadians grapple with mental-health issues year-round, but the conversation kicks into high gear every January on Bell Let’s Talk Day. That’s when telecom giant BCE Inc. commits to spending five cents on mental-health initiatives every time someone tweets their hashtag or watches their official video, and every time one of their subscribers texts or calls someone.

Still, the shortcomings and inequities of Canadian mental-health care cannot be resolved in single day: Psychiatric care is hard or impossible to find in some parts of the country, police are being forced into the role of front-line mental health workers, and, at school and in the workforce, Canadians’ need for care is growing. Here’s a look at some of The Globe and Mail’s recent reporting and commentary and a look at how the issues are playing out here in Canada.

Snapshots of #BellLetsTalk

Today is Bell Let’s Talk Day. For every view of this video 👇, Bell will donate 5¢ towards Canadian mental health initiatives. Watch now and retweet this post to help us spread the word! #BellLetsTalk pic.twitter.com/mesNKy6uAe

— Bell Let's Talk (@Bell_LetsTalk) January 29, 2020

It’s the 10th year of #BellLetsTalk and, while we’ve come a long way from where the conversation on mental health started, there’s still more work to do to end stigma & make sure Canadians can get the support they need. So let’s keep talking, Canada!

— Justin Trudeau (@JustinTrudeau) January 29, 2020

Today on #BellLetsTalk Day join us in having a conversation about mental health #EndTheStigma pic.twitter.com/oLOmApq4dn

— Doug Ford (@fordnation) January 29, 2020

A reminder on #BellLetsTalk day that @GovNL has many mental wellness supports available to both youth and adults. Bridge the Gapp is a way to connect with guidance and supports for mental health and addictions in NL.https://t.co/WJfYVqT5CR pic.twitter.com/xEepkjyis7

— Premier of NL (@PremierofNL) January 29, 2020

The psychiatry gap

Finding good psychiatric care is challenging enough in the big cities – Toronto, Montreal and Greater Vancouver – where more than a third of Canada’s psychiatrists are based. But in some places, it’s hard, even impossible, to find any local help at all. A Globe and Mail analysis found that half of Canadians live in regions with too few psychiatrists for the ratio recommended by a panel of experts with the Canadian Psychiatric Association. About 2.3 million were in areas with no permanent psychiatrists at all. That’s going to get worse in the coming years: Half the nation’s psychiatrists are older than 55, and low pay, long hours and high burnout rates are deterring young people from choosing psychiatry as a vocation.

But in her investigation, reporter Erin Anderssen also found experts exploring possible solutions: Requiring psychiatrists-in-training to do residencies in underserved areas, or making telepsychiatry more available to rural and northern patients. Dr. Saadia Sediqzadah, a resident at the University of Toronto, spent time in Iqaluit as an elective. Now she’s applying to work as a regular temporary psychiatrist there, a job she wouldn’t have considered if she hadn’t dared to travel north. “How do you know you like it if you don’t try it?” she said.

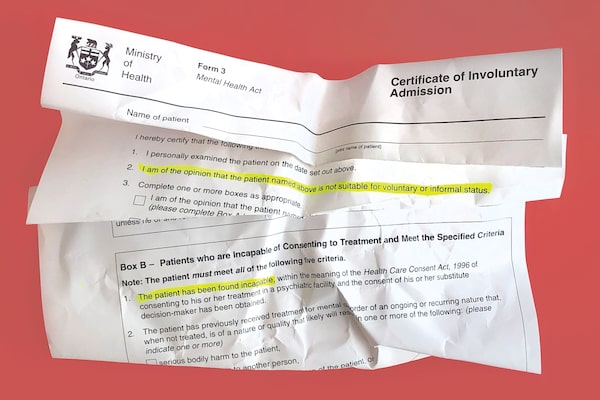

Coercive care

Photo illustration by The Globe and Mail

Anna Mehler Paperny is a former Globe journalist whose many attempts to kill herself – by drinking windshield-washer fluid, sleeping pills or antidepressants – are recounted with black humour in her recent memoir Hello I Want to Die Please Fix Me. Sometimes, she was sent to involuntary psychiatric care, an increasingly common practice in Ontario: Every month, more than 3,700 Ontarians are hospitalized against their will for mental-health reasons, she wrote for The Globe, and between 2008 and 2017, involuntary admissions in the province rose by nearly 90 per cent. She questioned why such a drastic measure is increasingly becoming the norm, and asked what could be done differently to balance patients’ safety with their dignity and rights:

Forms are a necessary psychiatric tool but their use is increasing, and they aren’t benign: They can kill someone’s trust in the medical system for life, which means they don’t seek help or make use of it when they truly need it. That possibility has to be weighed against whatever harm you think will come of letting a person make their own health decisions. Whether it’s resource scarcity or a lack of that power to persuade, clinicians are increasingly turning to coercion. Perhaps if we prioritized the kind of care people wanted – compassionate, evidence-based, ready when needed in the form people need it – coercion could become a tool truly rare.

Police on the frontlines

Dakota Dawthorne, shown with parents Michael and Nathan in their living room in London, Ont.GEOFF ROBINS/GEOFF ROBINS/The Globe and Mail

When Canadians’ mental illnesses lead them to hurt themselves or others, it’s more likely than ever that the police will deal with it. Forces across the country have seen years of increases in the mental-health-related calls they answer, the result of a decades-long shift from long-term institutional care to short-term solutions at overcrowded hospital emergency rooms. Last fall, Ms. Anderssen looked at the case of Dakota Dawthorne, an autistic Ontario boy whose parents, Michael and Nathan, had to call 911 when they feared for his safety:

We have dealt with outbursts, meltdowns and the house getting trashed. When we call the police, it is because, as a family, we can’t handle what is before us.

Students in need

Dr. Rina Gupta, director of counselling services at Queen's University, has a session with a patient.Johnny C.Y. Lam/the Globe and Mail/The Globe and Mail

Across Canada and the world, postsecondary students have been drawing more heavily on mental-health resources in recent years, and schools have been struggling and reorganizing to keep up. UBC, for instance, tried referring more students to external services so the school’s counselling staff could see more people. But the health-care sector is also feeling the strain as demand exceeds the supply of psychiatrists. Victoria Gibson’s investigation for The Globe led her to people like Dr. Rina Gupta, director of counselling services at Queen’s University, who described how school staff are facing more and more challenging cases of students in need:

“There have been a lot of students who have been very vocal about wait times or not being to access services, and that’s understandable if students are feeling stressed,” Dr. Gupta said. On a typical day, she says she often cancels prior commitments to address students showing up in crisis, who they try to accommodate right away. “I did that three times yesterday,” she said in a phone call.

As students headed back to school this fall, Ms. Anderssen also compiled a guide for parents to help stressed-out students, including the array of services schools typically offer.

Mental health in the workplace

Office towers loom over Toronto's financial district.Tijana Martin/The Canadian Press/The Canadian Press

The Toronto-based Centre for Addiction and Mental Health is also offering business leaders a playbook to address mental illness in the workplace, a problem CAMH says adds a $51-billion annual economic burden in sick leave, lost productivity and other costs. The goal is to encourage top executives to create organization-wide plans to deal with mental illness and learn how to recognize it in others and get co-workers the help they need. Cameron Fowler of Bank of Montreal, CAMH’s partner in the playbook campaign, said it’s a problem executives can’t ignore any more:

In order for CEOs and boards to believe that they’re going to have enduring short-, medium- and long-term success, the first and most important thing is the health of their leaders and their employees. I just don’t think there’s a way to avoid this any longer. CEOs need to own this. ... Go on record [and] take accountability that this is going to be fixed in their organizations.

Someone to talk to

If you need professional counselling right now or are having thoughts of suicide, call Kids Help Phone at 1-800-668-6868 or Crisis Service Canada at 1-833-456-4566, or visit crisisservicescanada.ca.

More reading

Editorial: Canada’s health-care system is failing people who need mental-health care

Mirko Bibic, Bell Canada CEO: It’s time to turn talk into action when it comes to mental health

Lindsey Lowy: My daughter’s mental-health crisis is forcing me to speak up

Naomi Titleman Colla: We are all responsible for creating greater wellbeing in the workplace

Elizabeth Renzetti: Who deserves mental health? It should be everyone

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.