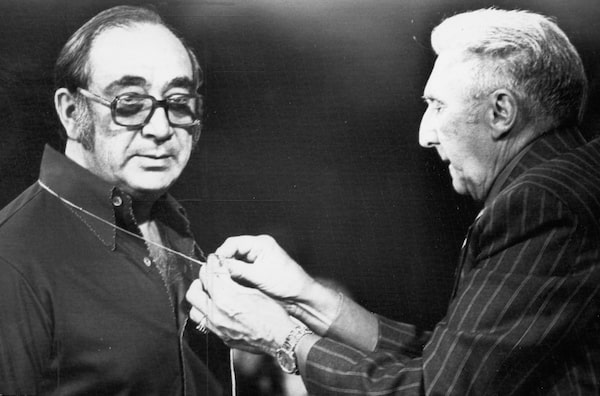

A clerk of the court places a microphone around the neck of former Montreal meat magnate William Obront in 1976. Mr. Obront was sentenced to one year in jail for his refusal to talk.The Canadian Press

William Obront, a Montreal meat merchant who once made front-page headlines across Canada after a public inquiry named him as a key money launderer for the Cotroni Mafia clan, has died.

He had been mixed up in three major scandals in the 1960s and 1970s, but vanished from the spotlight after getting a lengthy sentence for drug trafficking in Florida.

His death in Miami-Dade County – on Oct. 12, 2017, at the age of 93 – was not reported at the time, but The Globe and Mail confirmed it through Florida state records.

He was a behind-the-scenes figure in the Gerda Munsinger case, a Cold War scandal featuring sex, politicians and the spectre of Soviet spying.

He was also linked to Robert Samson, the rogue Mountie whose botched attempt to plant a bomb eventually led to the creation of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS).

Lastly, Mr. Obront was a prominent character in the hearings of a Quebec inquiry into organized crime, which publicized his ties to the mob and heard allegations that tainted meat had been sold at Expo 67.

“William Obront: Here’s a name that for years has continually emerged as much in police circles as before the public,” the inquiry, known by its French acronym, CECO, said in a 315-page report that focused on Mr. Obront.

The 1977 report said Mr. Obront was a “money mover” for the Montreal Mafia and its leaders, Vincenzo Cotroni and his successor, Paolo Violi.

Mr. Obront, who was nicknamed Obie, told the inquiry that he had donated to the Quebec Liberals, backing premier Robert Bourassa in the party leadership race against Claude Wagner.

A former justice minister, Mr. Wagner had been the first to raise Mr. Obront’s name publicly when he alleged in the legislature in 1967 that organized crime had infiltrated Expo 67.

Eight years later, when he took the stand at the CECO inquiry, Mr. Obront became a household name as Quebeckers learned of the tainted-meat affair.

CECO testimony showed that meat unfit for human consumption had been sold at Expo 67 and that firms owned by Mr. Cotroni and Mr. Obront shipped spoiled sausages.

Mr. Obront came from a family of butchers of Russian ancestry. One of the three children of Jack and Becky Obront, he was born in Montreal on March 20, 1924.

He started working at his uncle Ben’s butcher shop in the Atwater Market when he was 17 or 18, according to Ben’s son, Morty.

“My father loved him because he was a happy-go-lucky guy who always had a smile plastered on his face,” Morty told The Montreal Gazette in 1976.

Morty added that “Obie” was also nicknamed Diamond Jim, because of his lavish spending and love for gambling. He said William once got a $10,000 loan from his father-in-law to start his own business, but lost the money in a dice game.

By 1949, Mr. Obront owned his own retail outlet and four years later incorporated a meat-packing company. Within a few years, he came to the attention of the police as a shareholder in two nightclubs known as mob hangouts.

Around that time, a German woman named Gerda Heseler tried to settle in Canada. She had a criminal record and past contacts with Soviet intelligence, but gained entry by applying under her married name, Munsinger.

She worked as an escort in Montreal, associated with underworld figures and had an affair with Pierre Sévigny, the associate defence minister in John Diefenbaker’s Conservative government.

Mr. Diefenbaker ordered Mr. Sévigny to end the relationship after the RCMP warned that the minister had left himself open to blackmail or spying. The issue wasn’t revealed until 1966 when the Liberals were in power and taunting the Conservative opposition.

Mr. Obront later admitted before the CECO that he knew Ms. Munsinger. “She was going out with someone I knew, a politician,” he testified.

In fact, he was very close to her, close enough to play a role in one of the great scoops in Canadian journalism.

When the scandal erupted, Ms. Munsinger was thought to have died of cancer. The late journalist Robert Reguly said he spoke to Mr. Obront, who unwittingly revealed she was still alive. Mr. Reguly, then working for the Toronto Star, found her at her flat in Munich. He said that she told him “I thought you had been sent by Willie Obront to kill me.”

Mr. Obront’s connection to Ms. Munsinger wasn’t publicly revealed until the CECO was set up in 1972 and began holding televised hearings.

At the time, he declared average annual income of $33,000. The CECO report said that in fact he was an underworld financier who controlled nine bank accounts. Millions of dollars were deposited in those accounts, from illicit sources such as gambling or loan sharking, the report said.

By his own admission, one of his bank accounts was in the name of his chauffeur, Léo Robidoux, who could hand out cheques for him.

While the CECO hearings were unfolding, on the night of July 26, 1974, an RCMP Constable, Robert Samson, was severely injured while he tried to place a bomb outside the Montreal home of Melvyn Dobrin, president of the Steinberg supermarket chain.

An inquiry by fire commissioner Cyrille Delâge heard that in the preceding hours, Mr. Samson had visited Mr. Robidoux, the Obront chauffeur.

Mr. Samson said he had come to offer condolences to Mr. Robidoux’s wife, who had lost her brother. He told conflicting versions of the incident and was eventually sentenced to seven years in jail.

During his trial, he blurted that he had done “much worse” for the RCMP and disclosed that he had been part of a team that burglarized the offices of a Quebec news agency. His admission lifted the lid on the RCMP’s illegal operations against Quebec separatists. The ensuing uproar led to two public inquiries and the creation of CSIS to take over domestic spying from the RCMP.

Meanwhile, Mr. Obront left Canada, ignoring a subpoena to appear before Mr. Delâge’s inquiry.

Moving to Florida, he applied for U.S. citizenship. According to the CECO report, one of the two men who vouched for him, Barry Ressler, was an associate of the famous mobster Meyer Lansky.

Mr. Obront became a U.S. national in November, 1975. Under the law at the time, he lost his Canadian citizenship. Back in Quebec, he was charged with fraud and forgery and Canadian authorities sought his extradition.

He left for Costa Rica, but was expelled. In May, 1976, under police escort, he was flown back to Montreal. He refused to testify again before the CECO. In the fall of 1976, he pleaded guilty to the fraud and forgery charges.

Because he had forfeited his Canadian citizenship, he was expelled to the United States after his sentence. In Florida, he was arrested in 1983 as part of a ring trafficking cocaine and tranquilizer pills dubbed “the Canadian Connection.”

Found guilty and sentenced to 20 years, he then learned that U.S. authorities had revoked his American citizenship.

From the Lewisburg high-security penitentiary in Pennsylvania, he tried to apply for his Canadian citizenship certificate but was turned down. He then petitioned the Federal Court but was unsuccessful.

Mr. Obront, inmate number 12576-004, was released in March, 2002. At the time of his death, he was living at a retirement community north of Miami. His death certificate said he was a restaurant owner.

He was predeceased by his wife, Sarah Obront.

Tu Thanh Ha

Tu Thanh Ha