When Jean-Bernard Caron talks about the “before times,” he doesn’t mean 2019.

As curator of invertebrate paleontology at the Royal Ontario Museum, Dr. Caron’s focus is on an epoch that is crucial to the story of life on Earth and the foundation of our existence – yet consistently underplayed in books, documentaries and exhibits that make prehistoric superstars out of T-Rex and its kin.

Now, with the opening of a new permanent gallery at the ROM, dubbed “The Dawn of Life,” Dr. Caron is aiming to transform our understanding of evolution’s amazing journey before the dinosaurs came along – and long before mammoths, sabre tooth cats and our own primate ancestors were on the scene.

This is not simply the first chapter of life as we know it – more like the first several volumes of a rich drama that highlights some of biology’s greatest innovations, as championed by a cast of bizarre-looking heroes with unfamiliar names.

Yet it is these creatures that pioneered what it means to be an animal on Earth. As alien as they may appear to human eyes, they were the ones who made the first moves, caught the first glimpses, breathed the first breaths and took the first steps. Along the way, they invented exploring, socializing, protecting the next generation and the intricate, interdependent game of predator and prey. With virtually everything we do, we draw on their legacy.

Climate Innovators and Adaptors

This is one in a series of stories on climate change related to topics of biodiversity, urban adaptation, the green economy and exploration, with the support of Rolex. Read more about the Climate Innovators and Adaptors program.

To capture its significance using a more human-centric historical analogy, the subject of the new gallery is like the Roman Empire of life – except that many who wander through its fossil-rich displays will be learning about it for the first time. What they will see is something like a paleo-Pompeii – a remote past brought to life through an array of unique specimens, many of which have been waiting in storage for years or decades for just such a debut.

“One thing I would like people to take away is that life is very old,” said Dr. Caron during a walk through the new gallery ahead of its opening to the public on Dec. 4. “This was millions of years in the making.”

It’s an understatement. The gallery holds nearly 1,000 specimens from across geological time, starting with the very earliest traces of microscopic life around four billion years ago and ending about 200 million years ago in the Triassic – the period that saw the initial appearance of the dinosaurs, along with the reptilian order that would later give rise to mammals.

In between are key turning points, including Earth’s switch over to an oxygen atmosphere starting 2.4 billion years ago after the development of photosynthesis in bacteria. Samples of rock formations from Thunder Bay, Ont., and the Northwest Territories are the fossilized remains of bacterial colonies that were part of the change.

After them comes the initial rise of multicellular life, then the first animals, and then the great Cambrian explosion, about 500 million years ago, when evolution seemed to exult in possibilities and – as Stephen Leacock would say – rode madly off in all directions.

The stone at top, once the bed of a tidal flat, has the preserved tracks of an animal without vertebrae that moved between shallow waters and land. It's a long evolutionary journey from there to the Postosuchus kirkpatricki at bottom, a 218-million-year old dinosaur.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Cambrian creatures shown in model forms include Marrella, an early arthropod, and Haootia, believed to be the world's oldest animal with muscle tissue.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

To help bring the mysterious creatures to life, many of which exist only as faint outlines on flat grey rock, the exhibit is adorned with artist’s renderings and 3D-printed models that have the effect of turning stone into flesh.

Another highlight is a giant video wall that curves around visitors and visually immerses them in a Cambrian sea, where they can be eyewitnesses to an environment that gave rise to nearly every major phylum of the animal kingdom that we know today, along with many that have long since disappeared.

Dr. Caron, whose research specializes in this period, said he has been envisioning the new gallery for over a decade while heading up expeditions that unearthed some of its most recent and distinctive finds. Overall, Canadian fossils make up about two-thirds of what is on display, and with good reason, he added. Its vast and complex geology makes it one of the few countries in the world that could mount such an exhibit with native specimens.

“We had a really unique opportunity here,” Dr. Caron said. “The rocks of Canada have these wonderful stories to tell. I’m hoping this new gallery will give people, especially kids, the opportunity to find out about those stories, but also to get inspired about research.”

Joanna Wolfe, an evolutionary biologist and research associate at Harvard University whose PhD work focused on the Cambrian explosion, said that the power of a museum exhibit to fire the imagination cannot be overestimated.

Dr. Wolfe, who grew up in Toronto, said that it was an earlier and far less spectacular display at the ROM that set her on her life’s course before she was ten years old. “I became a scientist because of three cases of poorly lit Burgess shale fossils the ROM used to have,” Dr. Wolfe said. Describing how she became mesmerized that such strange creatures could have ever lived on Earth, she added, “They deserve to be seen in their glory.”

Details from a rock surface cast in Mistaken Point, N.L., show traces of some of the earliest multicellular organisms on Earth.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

There’s no question that the new gallery is built to enable that. In addition to throwing a bright spotlight on the Burgess shale formation, featuring specimens from multiple locations in B.C.’s Rocky Mountains, it also introduces visitors to three other Canadian UNESCO world heritage sites. These include:

- Newfoundland’s Mistaken Point, where early fern-shaped animal ancestors that predate the Cambrian left their impressions embedded in sedimentary rock.

- Miguasha on Quebec’s Gaspé Peninsula, where lobed-finned fish began the process that would eventually bring vertebrates onto land.

- The Joggins cliffs of Nova Scotia, which have yielded a spectacular trove of fossils from the Carboniferous Period, famous for its giant flying insects and for the emergence of the first, tiny reptiles – a sign of bigger things yet to come.

Including the Burgess Shale, the gallery features videos from all four locations to better connect the specimens on display to the places they came from. All are subjects of ongoing field research and are considered globally important to the study of life’s deep past.

Guy Narbonne, a professor at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., and a co-author of a recent report on geological world heritage for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, said that Canada’s bounty of fossil provides an strong throughline for the new gallery.

Dr. Narbonne, who has yet to see the gallery, said that based on what he knows of its contents, visitors are likely to perceive other themes that are equally striking. One is the intertwined relationship between life and global change, evident in the mass extinction events that have repeatedly truncated and redirected Earth’s biodiversity.

Four such mass extinction events are represented in the new gallery, including one of the most severe, which occurred during the Late Ordovician period, about 445 million years ago, when glaciers rapidly spread across the large southern continent of Gondwana and nearly 85 per cent of marine species on Earth disappeared. In the Dawn of Life gallery, that transition is captured in specimens from Anticosti Island, Que., where a case is also being made for designation as a World Heritage Site.

But while extreme climate change is considered the cause of that mass extinction event, exactly what triggered it remains a matter of debate. It could be a consequence of volcanic eruptions or a global transition in plant life. Either way, there is a sense of the past speaking across the eons to the world of today, with human civilization increasingly pushing the climate system and global biodiversity into uncharted territory. “Life has affected Earth and Earth has very strongly affected life,” Dr. Narbonne said.

The gallery's wall of trilobites, a type of arthropod that once teemed in the Earth's oceans until the Permian mass extinction.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Another such extinction event occurred at the end of the Permian period 252 million years ago and it extinguished the trilobites, one of the most abundant lineages of ancient life on Earth. In tribute to their enduring allure, the gallery features a “trilobite wall.”

ROM director and CEO Josh Basseches said that the trilobite wall stands out as one of his favourite elements in the Dawn of Life gallery. Another is an entire room dedicated to Ontario fossils, many of which were donated to the museum by residents and property owners who came across them by chance.

“I think it’s exciting to say that [the gallery] is also about the place where we live today,” he said. “It’s the excitement of it being close to home.”

Several private donors contributed to the new gallery, led by philanthropists Jeff Willner and Stacey Madge, whose $5-million gift in 2018 provided the means to get the project from the drawing board to the museum floor.

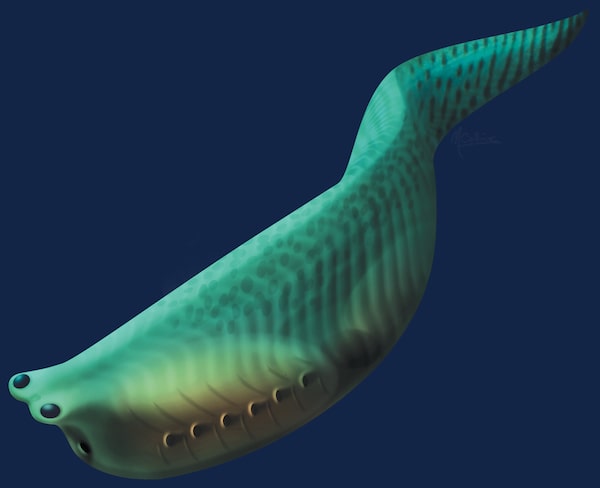

Dr. Caron said their enthusiasm for the project encouraged him and other museum staff to create a gallery that, in its look and feel, does not short-change or shy away from the complexity and diversity of early life, right down to the tiny wriggling Metaspriggina walcotti, a 506 million year old proto-fish that was a likely precursor to vertebrates and therefore to humanity.

“We wanted to give people a chance to understand themselves and the origins of the life they see today,” Dr. Caron said. “I think in some way, they will discover their own history here ... and maybe respect life a little bit more.”

Wonders of the ancient world: The artists’ view

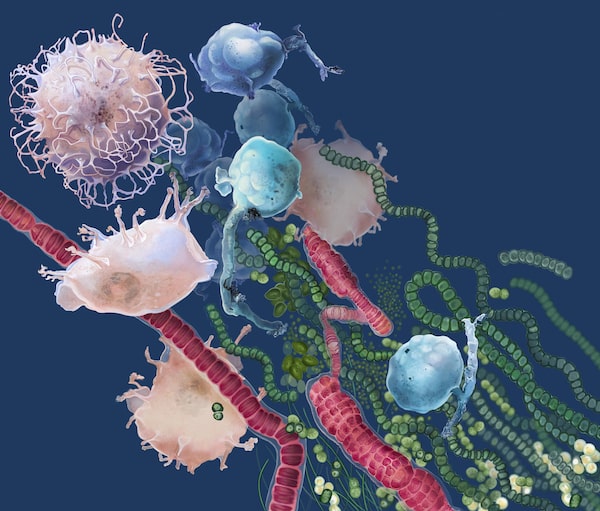

Single-celled organisms emerged in the Precambrian era, the little-understood span of time between the formation of the Earth and the emergence of more complex creatures about 540 million years ago.Illustration by Alix Lukas

In the next stage of geological time, a 'Cambrian explosion' of new species emerged with features that later life-forms would take for granted. Metaspriggina walcotti, a 506-million-year-old proto-fish, had vertebrate muscles and a pair of strong gill arches that suggest the first evolutionary steps toward jaws.Illustration by Marianne Collins

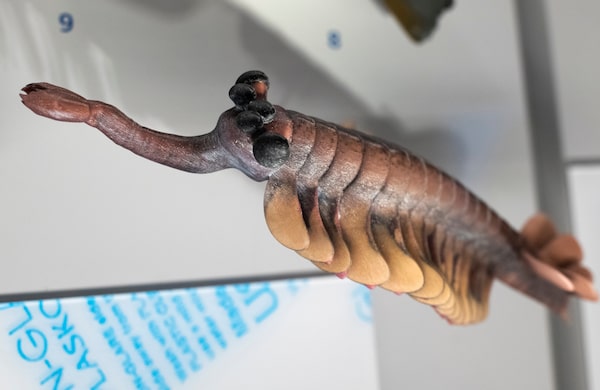

Cambroraster, a Cambrian predator depicted in model form, had a huge shielded head and comb-like claws to scoop food into its mouth.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Another Cambrian creature was Opabinia, which had five eyes on top of its head and a clawed arm dangling above its mouth.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Hallucigenia, a worm-like creature with spines and mutiple pairs of legs, was one of the most iconic Cambrian species to have been found in the Burgess Shale, a fossil deposit in B.C.'s Rocky Mountains where animals' soft parts stayed in unusually good condition.Illustration by Danielle Dufault

Elpistostege watsoni, a lobe-finned fish, lived in the Late Devonian period, about 375 million years ago. This depiction was based on a specimen from Miguasha National Park in Quebec.Illustration by Danielle Dufault

A giant millipede explores the forests of Nova Scotia about 319 million years ago. Joggins Fossil Cliffs on the Bay of Fundy, which the scene depicts, is a valuable record of the Carboniferous period, or 'coal age,' so named because its swampy forests became much of the Earth's modern-day coal deposits.Illustration by Danielle Dufault

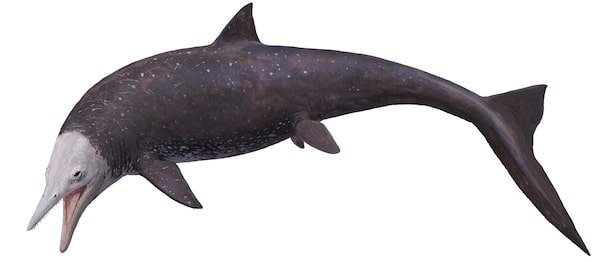

During the Triassic period, an unwary sea creature might have run into Macgowania janiceps, an icthyosaur, and become its next meal. The ROM's new gallery ends its narrative with the Triassic, when dinosaurs and reptiles emerged.Illustration by Joschua Knüppe

Ivan Semeniuk

Ivan Semeniuk