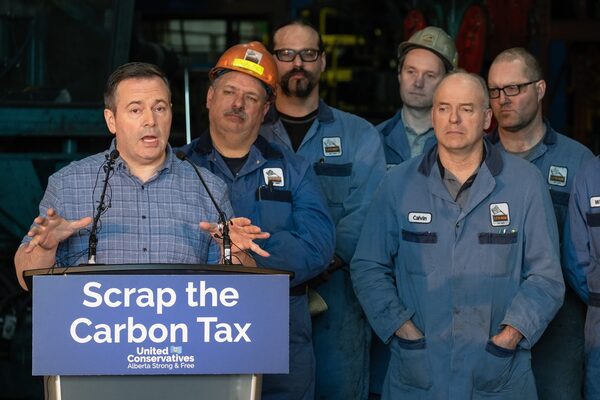

United Conservative Party Leader Jason Kenney speaks during a news conference at the Lethbridge Iron Works in Lethbridge, Alta., on March 20, 2019.David Rossiter/The Canadian Press

Four years ago, Justin Trudeau’s Liberals watched Alberta’s election with a thrilling sense that a frontier was opening up to them.

Like everyone, they were surprised by Rachel Notley’s ascent to the Premier’s office. But they viewed her New Democrats’ stunning end to nearly a half-century of Progressive Conservative rule as evidence that the province could be ready to break with Conservative hegemony federally, too. Months later, the Liberals picked up four Alberta seats for their best showing there in decades.

This spring, the Liberals are less wide-eyed. It’s not just that Ms. Notley is likely to lose office in the election set for April 16. Whatever happens with her, their own prospects in Alberta – where they are widely blamed for delays in pipeline construction, and related (if broader) economic woes – are back to being bleak.

But, the Liberals may still see an opportunity coming out of this campaign.

Its likeliest result – a return to power for the right, under United Conservative Party Leader Jason Kenney – could provide them with a useful foil during their own re-election campaign in the fall. And the extent to which they use him as such could provide a test of how much Mr. Trudeau and his party have hardened.

A common perception is that Mr. Kenney’s victory would add to the Liberals’ current woes. In terms of federal-provincial relations, he would join an already daunting group of Conservative premiers – Ontario’s Doug Ford, Saskatchewan’s Scott Moe, Manitoba’s Brian Pallister, New Brunswick’s Blaine Higgs – as Mr. Trudeau’s antagonists, particularly on carbon pricing.

But, in the run-up to October’s federal vote, the Liberals have to worry about rallying the centre-left behind them and motivating supporters to come out and vote. With some of Mr. Trudeau’s lustre having worn off even before the SNC-Lavalin scandal hit this winter, he is likely to run a more negative campaign than previously, pushing that he’s the only thing standing in the way of right-wing populism overtaking the country. And since federal Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer may not strike enough fear in the hearts of Liberal supporters on his own, Mr. Trudeau will look to lump him in with allies disliked by most people who would consider voting Liberal.

Among the current premiers, Mr. Ford is the most obvious such target. But Mr. Kenney, if elected, could easily find his face plastered alongside Mr. Ford’s in Liberal attacks.

One of the top ministers in Stephen Harper’s government, Mr. Kenney is more of a household name outside his own province than the likes of Mr. Moe, Mr. Pallister or Mr. Higgs. He is associated with a level of social conservatism that Liberals love to campaign against. And crucially, he stands to be more strident in his defence of oil-sands development, and more hostile toward environmentalism, than any Alberta premier since climate-change concerns entered the public consciousness.

Consider some of the most important battlegrounds for the Liberals this election. Quebec, where they hope to pick up seats, is more suspicious of Alberta’s resource sector than any other province. And in parts of British Columbia where the Liberals need to at least keep what they have, anti-pipeline sentiment runs high. Meanwhile, younger voters across the country – who came out in droves last election and are at risk of staying home this time – could see more urgency in the Liberals’ carbon-tax fight with Mr. Scheer’s Conservatives if Mr. Trudeau effectively highlights Mr. Kenney’s presence.

As for where potential Liberal supporters would rally behind Mr. Kenney: Other than Alberta, where the few Liberal MPs seeking re-election face long odds regardless, the most obvious place is Saskatchewan, where the Liberals hold one seat.

If that seems to make it an easy decision for Mr. Trudeau to campaign against Mr. Kenney if the latter emerges victorious next month – well, it shouldn’t.

Despite considerable skepticism among Liberals, Mr. Trudeau’s campaign team prioritized winning a seat or two in Alberta even before the 2015 provincial election made it seem less quixotic. That didn’t have much to do with their path to power. It was about proving they were a truly national party, breaking with divisive regional politics. Mr. Trudeau would set himself apart from his father, who infuriated Alberta with his energy policies, and other Liberal leaders who followed.

Mr. Trudeau could contend that he did his best, his government going so far as to buy a pipeline, and he’s been met only with anger. He could also argue that carbon pricing is enough of a core value for him that he welcomes a brawl with anyone who opposes it.

But if he winds up playing to negative perceptions of Alberta elsewhere, it would be among the clearest signals of how his approach to politics has darkened. It would put him more in line, in how he sees the electoral map, with someone like Jean Chrétien - about the furthest thing from the generational change agent he was billed as.

Mr. Chrétien, though, won a lot of elections. Mr. Trudeau is at serious risk of losing after one term. And as he may well be reminded when the votes are counted in Alberta next month, it’s not 2015 anymore.

Adam Radwanski

Adam Radwanski