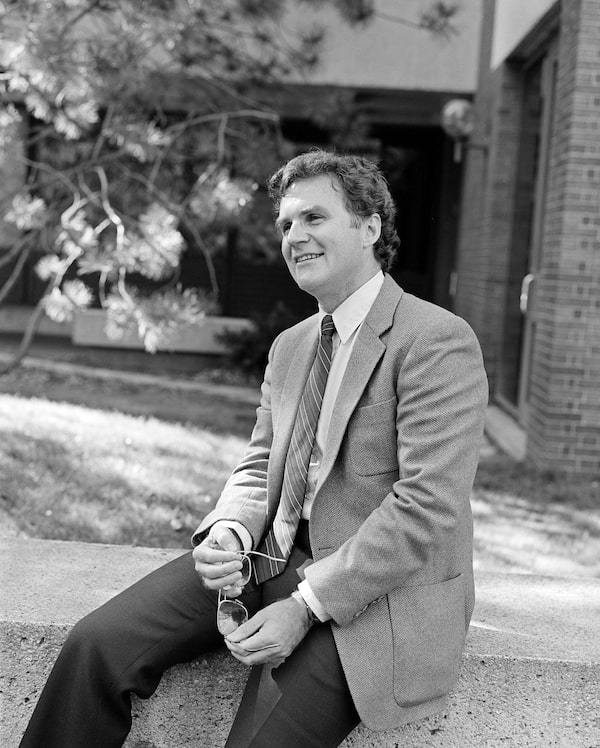

Although the idea of a notwithstanding clause was not new, Paul Weiler had laid out a persuasive case for it in a lecture reprinted in the Dalhousie Law Journal in 1980.Courtesy of Harvard Law School Archives

Paul Weiler was an outstanding legal scholar, breaking new ground in labour and sports law in Canada and the United States, as part of a trail-blazing career that also touched on a wealth of other social and constitutional issues. Describing himself as “a radical moderate,” Mr. Weiler strove constantly for legal reforms to bring more equity and fairness to society, particular for workers.

Yet, none of the remarkably eclectic accomplishments he chalked up had quite the impact of his advocacy of a notwithstanding clause in a Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Such a clause, allowing for legislative over-rides of certain sections of the Charter, proved critical to the 11th-hour compromise, known to history as The Kitchen Accord, that brought Canada a Constitution, which included a Charter of Rights.

Although the idea of a notwithstanding clause was not new, Mr. Weiler had laid out a persuasive case for it in a lecture reprinted in the Dalhousie Law Journal the year before, in 1980. His thesis was circulated among some of the central participants in the constitutional talks. “It was more than in the air. It was in their minds,” recalled former prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s principal secretary at the time, Tom Axworthy. “His timing was impeccable.”

With talks on the verge of collapse, the clause, which remains controversial 40 years later, was resurrected to seal a last-minute deal. It motivated premiers who were strongly opposed to an entrenched charter interpreted solely by judges, as was Mr. Weiler, to come on board. “It cut the Gordian knot between those who were terribly afraid of the Charter and those of us who very much wanted it,” Mr. Axworthy said. Without it, he said, Mr. Trudeau would have pushed ahead with a national referendum on the Charter that would have been both risky and divisive. Attested Saskatchewan’s then attorney-general Roy Romanow, who was part of The Kitchen Accord: “Weiler’s idea was key. No doubt about it.”

Mr. Weiler died July 7, after a 20-year battle with a rare, degenerative neurological disease, primary lateral sclerosis. He first made his mark as chairman of the powerful British Columbia Labour Relations Board in the mid-1970s. It was the first administrative tribunal in North America with total jurisdiction over labour relations, wiping out the role of the courts. The bold step was part of the progressive new labour code brought in by BC’s first NDP government in 1973. Mr. Weiler had been one of the architects of the code, which resonated across the country. It tilted the balance away from employers, and brought a measure of peace to BC’s ongoing labour wars. Over the next five years, his compelling, erudite rulings – models of clarity and fairness – gave the board the credibility it needed to prevail. When a right-wing Social Credit government replaced the NDP halfway through his term, both employer and union representatives told them not to touch the labour board, or Mr. Weiler. Some of his LRB judgments continue to be cited today.

Around the same time, Mr. Weiler ruffled judicial feathers across Canada with a critical assessment of the Supreme Court of Canada, In the Last Resort. The book reproved the court for its conservatism and lack of judicial activism. “It was quite daring for its time and remains one of the finest books produced by a constitutional law scholar in Canada,” said Harry Arthurs, professor emeritus at York University’s Osgoode Hall Law School, and an early professor of Mr. Weiler’s, who helped steer him towards his interest in labour law.

After his dazzling stint at the BC labour board, Mr. Weiler was lured to Harvard University as head of its Mackenzie King program to promote Canadian studies at the university. He was soon a full professor. Specializing in labour law, he revived Harvard’s trade union program, while endeavouring to shift labour relations in the United States away from decades of employer dominance. It proved an uphill struggle.

In 1993, Mr. Weiler was named chief counsel of the Dunlop Commission, established by then U.S. President Bill Clinton to consider the future of worker-management relations. The commission’s report recommended numerous pro-worker changes, including worker councils, to bring more balance to the workplace.

Mr. Weiler’s attention, meanwhile, had never wavered far from another of his great passions: sports. As big money and player associations seeking to relieve the yoke of ownership became increasingly significant, he realized sports and law were intersecting in ways they hadn’t before.

In 1992, he launched a sports and law seminar at Harvard, overcoming university fears it might be a frivolous matter for the prestigious law school. It was anything but. Full credit courses on sports are now in place at most law schools in the country, and Mr. Weiler was soon the go-to person on sports law.

Veteran hockey man Brian Burke, currently president of the Pittsburgh Penguins, was among a handful of students enrolled in Mr. Weiler’s historic first sports law seminar. “He was a pioneer,” Mr. Burke said. “Paul told us that we were on the cutting edge, that this was the start of something that was going to grow, and he was right. It was exciting.”

At one point, he was considered as a possible commissioner for the NHL, before Gary Bettman got the job. Sports and the Law, co-authored by Mr. Weiler, was the bible on the expanding field for the next 20 years. “I think his place in the constellation of legal minds in the history of Canada is secure,” Mr. Burke said.

Mr. Weiler later added a course on entertainment, media and the law and wrote a book about that, too, laughing that he could now claim movie tickets as a tax expense. His interests kept widening, adding authoritative work on medical malpractice, health policy and tort reform, plus an earlier review of Workers’ Compensation for the government of Ontario that led to fundamental changes. “When it came to the field of law, he was polygamous,” Prof. Arthurs said.

Paul Cronin Weiler was born Jan. 28, 1939, in Port Arthur, Ont., (now part of Thunder Bay). His father, Gerard Bernard (Bernie) Weiler was a prominent lawyer. He met Marcella Cronin at a street dance in Ontario’s rural Bruce County, introduced by his brother, Biff. They married in 1936. After time as a young lawyer in the northern gold rush town of Geraldton, Ont., Bernie Weiler moved the family to Fort William, Ont., to set up practice with his brother, a firm that remains under the Weiler name.

Canadian-born Harvard law professor Mr. Weiler's love of law was imbued in him by his father Gerard Bernard Weiler.John Rich/Courtesy of Harvard Law School Archives

In addition to imbuing Paul with a deep love of law, his father encouraged his embrace of sports. Family vacations often coincided with sporting expeditions, south to Minnesota for baseball and football, and once to Wisconsin to watch the Green Bay Packers. “Sports was part of the love language of our family,” said Paul’s youngest brother, Joe.

Academically, Paul Weiler always stood first, from public school to Osgood Hall. Prof. Arthurs remembered that Mr. Weiler would remain inconspicuous in his law classes throughout the year. “Then at the end of term, he would put in a brilliant exam-writing performance.”

After graduating, Mr. Weiler went to Harvard for a Master of Laws in 1965. He returned to Osgoode as a professor, before shifting to B.C. for his five years as head of the labour board. In 1963, Mr. Weiler had married Barbara Forsyth, a high school teacher in Thunder Bay, who grew up in Neepawa, Man., hometown of famed Canadian writer Margaret Laurence. The couple had four children. They divorced in 1981. Mr. Weiler’s second wife, Florrie Darwin was a chemistry teacher at the University of Maine when they met.

Mr. Weiler had a genial, down-to-earth personality that helped break down barriers between the so-called ivory tower and the real word. He showed, wrote Canadian labour economist Morley Gunderson, that it was possible to be “a sports nut and a world-renowned academic and policy and political advisor.”

He had a relentless thirst for knowledge and sharing it, no matter the topic. During a sabbatical in Paris, Mr. Weiler compiled thorough guides to the city’s art and architecture. He also published a newcomers’ guide to Harvard and the surrounding city of Boston.

After his PLS diagnosis, Mr. Weiler was able to teach and write for a few more years, before stepping aside, as his physical stamina and ability to communicate diminished.

Confined to a specialized motorized chair, with little ability to speak except by computer, Mr. Weiler accepted his fate without complaint. Cared for by Ms. Darwin, caregivers and supportive friends, he displayed remarkable affability throughout his difficult last years and continued to enjoy Boston Red Sox games at Fenway Park. “His spirits never plummeted,” Joe Weiler said. “For him, every day was a gift, and the glass was always half full.”

Mr. Weiler was awarded the Order of Canada in 2016.

He leaves his wife Florrie, siblings Bob, Susan and Joe, children Virginia (Paul), John (Lisa), Kathryn (Sarah) and Charlie (Katie), and caregiver Angelita Altea.