The stained-glass window, known as 'the Ottawa Window' to the art world and 'the East Window' to the St. Bartholomew’s congregation, is hidden in plain sight, according to the church's Rev. David Clunie.Dave Chan/The Globe and Mail

There are many ways you could describe the astonishing stained-glass window that stands over the altar of Ottawa’s St. Bartholomew’s Anglican Church, a few steps from the grounds of Rideau Hall. Rector Rev. David Clunie puts it like this: hidden in plain sight.

He means this in a religious way: “Jesus is here, God is here – but we don’t see it.”

Hidden in plain sight, however, could equally apply to the work itself, considered the crowning achievement of the Dublin-based stained glass artist who created it.

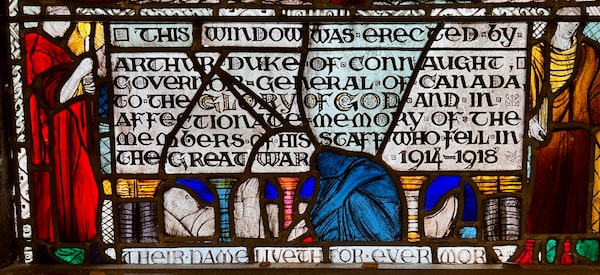

Shirley Ann Brown, a professor of art history at York University and a recognized expert on stained glass art, says the First World War-era window “is significant in the world of stained glass for two reasons: as the work of the artist, Wilhelmina Geddes, and because of its artistic style and qualities.” The colourful window depicts slain soldiers rising to heaven and being welcomed by saints, kings, famous soldiers – and even mythical figures.

Ms. Geddes herself is significant as she was among the first women to forge a career in a traditionally male-dominated profession, with her pioneering work emerging around 1910. “Her artistry,” Prof. Brown says, “was personal and idiosyncratic – unlike anything seen in her contemporaries.”

Ottawa’s St. Bartholomew’s Anglican Church is a few steps from the grounds of Rideau Hall.David Clunie/Handout

In a 1994 article in Irish Arts Review, Prof. Brown said, “It is time that the window placed in the little-known St. Bartholomew’s Church on a quiet Ottawa street was given its due not only as a war memorial, but as a turning point in the history of stained glass in Canada.”

Didn’t happen then, but Ms. Geddes’s window – her only known work in North America – has been waiting 103 years to be recognized and it still could happen. Speaking after a Remembrance Day service last November, Irish Ambassador Eamonn McKee suggested the window – known as “the Ottawa Window” to the art world, “the East Window” to the St. Bartholomew’s congregation – “is not simply a masterpiece of Irish art. It is a symbol of the extraordinary journey of Ireland in the 20th century.”

Mr. McKee and his wife, Mary, had previously seen pictures of the window – “but nothing prepares for its presence illuminated by the sun. It is stunning, such a dramatic narrative, impossible to capture its beauty in reproductions.”

The church known to locals as “St. Bart’s” was founded in 1867, eight weeks after Confederation was proclaimed. According to Canadian historian Charlotte Gray, herself a member of the congregation, a city directory of the time described the stone building as “a chaste little structure without external adornments.” It was, then, “anything but striking or attractive.”

The window – which took Ms. Geddes four years to complete (1915-1919) – changed that drab dismissal in an instant when it was unveiled on Nov. 9, 1919, by none other than 25-year-old Edward, Prince of Wales, the future king who would famously abdicate in 1936 after less than a year on the British throne.

Irish Ambassador Eamonn McKee suggested the window 'is not simply a masterpiece of Irish art. It is a symbol of the extraordinary journey of Ireland in the 20th century.'David Clunie/Handout

There was, history records, “an audible gasp” from the 200 or so loyal parishioners gathered for the ceremony. No one had ever seen anything quite like this huge, colourful and extraordinarily busy stained glass window.

Rev. Francis Henry Brewin, rector at the time of the unveiling, sent a thank you note to Ms. Geddes, noting that his wife, Amea, “says that now it does not matter if the sermon is dull; there is so much to think about in the window. I myself like to be constantly discovering some new detail; ‘too much detail’ is a criticism I cannot accept, and after all, I live more or less with the window and ought to be a judge on that point. I find the window grows on me, and I love it more the whole time.”

“The glass itself is in great shape,” Canon Clunie says of the more-than-a-century-old window. Not so the framing and structural support. The church is hoping to raise $250,000 for restoration that will begin this summer. Ireland has already committed $40,000 to the project. Former governor-general David Johnston and his wife, Sharon, were both regular worshippers while at Rideau Hall, and Mr. Johnston is the fundraising campaign’s honorary chair.

Multiple governors-general, not all of them Anglican, have attended service at the little church. The Micheners, Roland and Norah, had such affection for it that their ashes are embedded in one wall.

This focus on restoration led, not surprisingly, to researching the original idea behind the window and Ms. Geddes’s effort to complete it – a journey fraught with disagreements, arguments and changes in direction.

Ms. Geddes titled her work The Welcoming of a Slain Warrior by Soldiers, Saints, Champions and Angels. Historian Ms. Gray says the work was created during a time of “Muscular Christianity, where men fought and women wept.” Indeed, there is much battle reference in the work as well as multiple mourners weeping, most of them women.

Ms. Geddes titled the stained-glass window 'The Welcoming of a Slain Warrior by Soldiers, Saints, Champions and Angels.'David Clunie/Handout

The window was started during the Great War and completed shortly after it ended. Ms. Geddes was working in Dublin at a time of the Irish rebellions against Home Rule, a period the poet Yeats described as “a terrible beauty.”

The Duke of Connaught, Prince Arthur, was governor-general of Canada from 1911 to 1916. When war broke out in 1914, his staff members began signing up and shipping overseas to fight for Britain, several of them fighting for the newly formed Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, which had been named in honour of the governor-general’s popular daughter. By war’s end, 10 staff members had fallen, never to return to Rideau Hall.

The Duke and Princess Louise had close friends who had lost a son early on in the war. An invitation to come to Canada was extended to Sir John Leslie and Lady Leoni. The Connaughts believed a visit overseas would help the Leslies in grieving the loss of their son, Norman, who had been killed in action in the fall of 1914.

As Lady Connaught had already improved much within the little church – candles, carpets, a curtain for the blinding window over the altar – it is believed that this visit led to the suggestion that, with Lady Leslie’s help, they commission a stained-glass window as a memorial to the lost staff members.

Lady Leslie, who was very connected to the British art scene, offered the commission to her friend, Sarah Purser, founder of an innovative stained-glass studio in Dublin known as An Tur Gloine (Tower of Glass). Ms. Purser awarded the commission to 32-year-old Ms. Geddes, then a relatively unknown Belfast artist.

Creating the window was a painful and lengthy process, as Prof. Brown details in her article, with Ms. Geddes forced to mail her ideas off to Ms. Purser in Dublin, who would then pass them on to Lady Leslie and Princess Patricia, who was also involved, for comment. There was much disagreement. Ms. Geddes wondered in one letter if Canadians would understand her innovative and eccentric art.

Ms. Geddes never received the praise due for such a work, yet – fighting depression and poverty – she continued to turn out stained-glass creations until her death in 1955 at the age of 68.Dave Chan/The Globe and Mail

They argued over St. Michael’s presence, which Ms. Geddes felt made the window appear too close to the Last Judgment. She balked at putting in Joan of Arc. “I don’t want ladies in it,” she said in one letter, “as it’s meant to be warlike.” She lost that argument, so decided to portray Joan on horseback heading into battle at Orleans in 1429. She added King Arthur and his knights, mythical figures in a religious scene. She wanted saints instead of centurions. She put in the Angel of Healing, Raphael; the Angel of the Annunciation and Resurrection, Gabriel; as well as the Angel of Death and the Angel of Peace. She added the Roman soldier Longinus, who was believed to have pierced the crucified Christ’s side to make sure he was dead.

When Ms. Geddes said she wanted to have the deceased soldiers rising to heaven on flying horses, it was rejected as being “too operatic.”

She wanted the dead warriors to be greeted as men, not as rising dead. As Prof. Brown noted in her article, Ms. Geddes “created a new male prototype for stained glass – modern-looking figures, close-shaven, classically-derived young men, serious and thoughtful.” She got her way.

Eventually the four women came to an agreement on the overall design and Ms. Geddes was told to begin. She would receive as commission the sum of £500. Prof. Brown estimates the work today would cost in the range of $200,000 to complete.

Princess Louise, alas, never got to see the window she had commissioned. The Connaughts had returned to England in 1916 and she passed away before it could be completed. The Duke did see it in London, before it was shipped to Canada.

Ms. Geddes never received the praise she was surely due for such a work. She fought depression and poverty but continued to turn out stained glass creations. She died in London in 1955 at the age of 68.

The Anglican Church did little to nothing in terms of promoting and exhibiting her window. “I don’t think the clergy wanted it to be highlighted,” Canon Clunie says. “Most clergy don’t like this window. They see it as too militaristic, that it glorifies war.”

In her depiction, Ms. Geddes wanted the dead warriors to be greeted as men, not as rising dead. She is cited as creating 'a new male prototype for stained glass.'David Clunie/Handout

There are other military connections at St. Bartholomew’s, as it serves as the official chapel for the Governor-General’s Foot Guards and the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry has a “dedicated pew.”

Canon Clunie says the Ottawa Window was “opaque to congregation for years, but then it began to be decoded.”

Decoded in part, but forever mysterious. It is curious how the window, all these decades later, still speaks differently to those who see it with the morning sun pouring through the stained glass.

Mr. McKee said last fall that, for him, the window remains “a signpost to a future of British Irish relations in the 21st century. Notwithstanding Brexit, we will build a new bilateral relationship with Britain. It will be the work of a generation.”

Peter Raymont, the acclaimed filmmaker with Toronto-based White Pine Pictures, figures he has spent a lifetime deciphering the window, as he grew up in the church and, only last year, buried his 104-year-old mother, Mary, whose funeral was held there.

“As a boy,” Mr. Raymont recalls, “I spent every Sunday morning sitting awkwardly with my mum, dad, elder sister and younger brother in a hard wooden pew near the front. … While I enjoyed singing hymns, countless hours were spent listening to endless sermons while my eyes wandered over the huge stained-glass window above the altar. I found it difficult to decipher, with huge knights on horseback, ‘Christian soldiers,’ I imagined, marching off to war. There were many angels, some playing harps, others wearing armour. There were men with halos carrying spears – perhaps Christ’s apostles? And behind the massive figures, there were tiny scenes I couldn’t make out … the crimson and yellow and blue glass added a magical presence to the neighbourhood church and, while imposing, it was also strangely comforting, as it was forever there, unchanged.”

“I’ve seen the window hundreds of times,” Canon Clunie adds, “and I’m still seeing things.

“Every day it looks different because of the light.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Roy MacGregor

Roy MacGregor